Subscribe now to get notified about IU Jharkhand journal updates!

Children's Buying Behavior For Food Products : Review Of Scope And Challenges

Abstract :

Children are seen as large flourishing consumer market. The purpose of the study is to review the available literature and assess how children act as consumers. Focusing on the food choices made by the children this study reveals the developmental sequence characterizing the growth of consumer knowledge, skills, and values as children mature throughout childhood and adolescence. Children place higher level of trust in interpersonal information sources, especially in their parents who are perceived as the most credible information source with respect to their learning about new food products. The food choices made by children seemed to involve cognitive self-regulation where conflicting values for food choices were integrated and brought into alignment with desired consequences. Children's perceptions of the value of their parents' efforts to use television advertisements make a positive contribution to their consumer socialisation. Based on the evidence reviewed, implications are drawn for future research in the field of children's consumer behavior.

Keywords :

Children, Consumer Behavior, Food choice, Consumer socialization.Introduction :

The market of food and eating items is increasing day by

day. The food marketers are targeting children and

adolescents as customers with intention to affect their

food choice, food preference and ultimately food buying

behaviour. Market research shows that children wield

considerable power as consumers, and their influence on

family purchases goes beyond the selection of toys and

cereals. Children also exert a substantial influence on their

parents' consumer decision making and spending

(Hawkins et al., 2001). Blackwell et al. (2001) states that

adolescent influence on household spending varies by

product user and by degree. They have a greater influence

in decisions on purchases of products for their own use.

Though there have been many scholarly researches on

consumer behaviour of children there is lack of systematic

research on the consumer behaviour of children, and

specifically the influence or role of consumer socialisation

agents (such as parents, peers, retailers and school), can

possibly be ascribed to the fact that marketers may think

that it is inappropriate to regard children as a "market"

(McNeal, 1973). The effects of advertising (and the role of

the mass media as a socialisation agent) on children have,

however, been the subject of considerable research during

the past three decades (Meyer, 1987; Roedder, 1981;

Macklin, 1987; Yavas & Abdul-Gader, 1993; Cardwell-

Gardner & Bennett, 1999). The findings of a recent study

by Carlson et al. (2001) indicate that parental styles plays

vital role in determining the manner in which mothers

socialise their children about television and television

advertising. Children are difficult to study, and today's

children live in a rapidly changing technological world.

Research must therefore be undertaken to understand the

consumer behaviour of children, and to ascertain the

reasons why they feel and act the way they do.

In the Indian context, a limited number of studies have so

far investigated the consumer behaviour of children. In

order to assess the consumer behaviour of children it is

very important to analyse the consumer socialisation

process. A broad overview will be provided of the nature

and processes of consumer socialisation and the research

conducted in this field during the past few decades. A

number of important marketing implications with respect

to children's buying behaviour are discussed.

Objectives of the Study

The study is exploratory in nature and done with help of

reviewing the previous findings in the field of consumer

behaviour of children. Thus the objectives of the study are

as follows :

- To review the consumer socialisation process of children and identify the agents of consumer socialisation

- To review the impact of promotional activities on the food buying behaviour of children.

Consumer socialisation of Children : An Overview

The process of consumer socialisation of children moves

through various cognitive and social phases on their

journey from birth to adolescence and adulthood.

Consumer socialisation (which is only a part of a child's

general socialisation) is described as "the processes by

which young people acquire skills, knowledge, and

attitudes relevant to their functioning as consumers in the

marketplace" (Ward, 1974). Although McNeal (1993)

sometimes refers to it as "consumer education" or

"consumer development", Ward's description of the

concept can be regarded as a universally accepted

definition (McGregor, 1999; John, 1999; Carlson &

Grossbart, 1994). John (1999) views consumer socialisation

as a process that occurs in the context of social and

cognitive development as children move through three

stages of consumer socialisation, namely the perceptual

stage (3-7 years), the analytical stage (7-11 years), and the

reflective stage (11-16 years). This latter stage, which is

particularly relevant for this study, is characterised by the

development of information processing skills (such as

interpreting advertising messages) and social skills.

Children pay more attention to the social aspects of being a

consumer (John, 1999). According to Acuff (1997), peers

play an enormous role when teenagers have to make

buying decisions in this early adolescent stage. These early

teenagers are also very activity oriented, for example

taking part in organised sport, playing computer games,

viewing television programmes, engaging in various

school activities and shopping (Acuff, 1997). Blackwell et

al. (2001) are of the opinion that children learn their

consumer skills primarily from shopping with parents - a

phenomenon these authors call "coshopping." Coshoppers

tend to be more concerned with their children's

development as consumers and they "…explain more to

their children why they don't buy products", which to

some extent "…may mediate the role of advertising."

(Blackwell et al., 2001). McNeal (1993) states that children

pass through the following five-stage shopping learning

process in their consumer development :

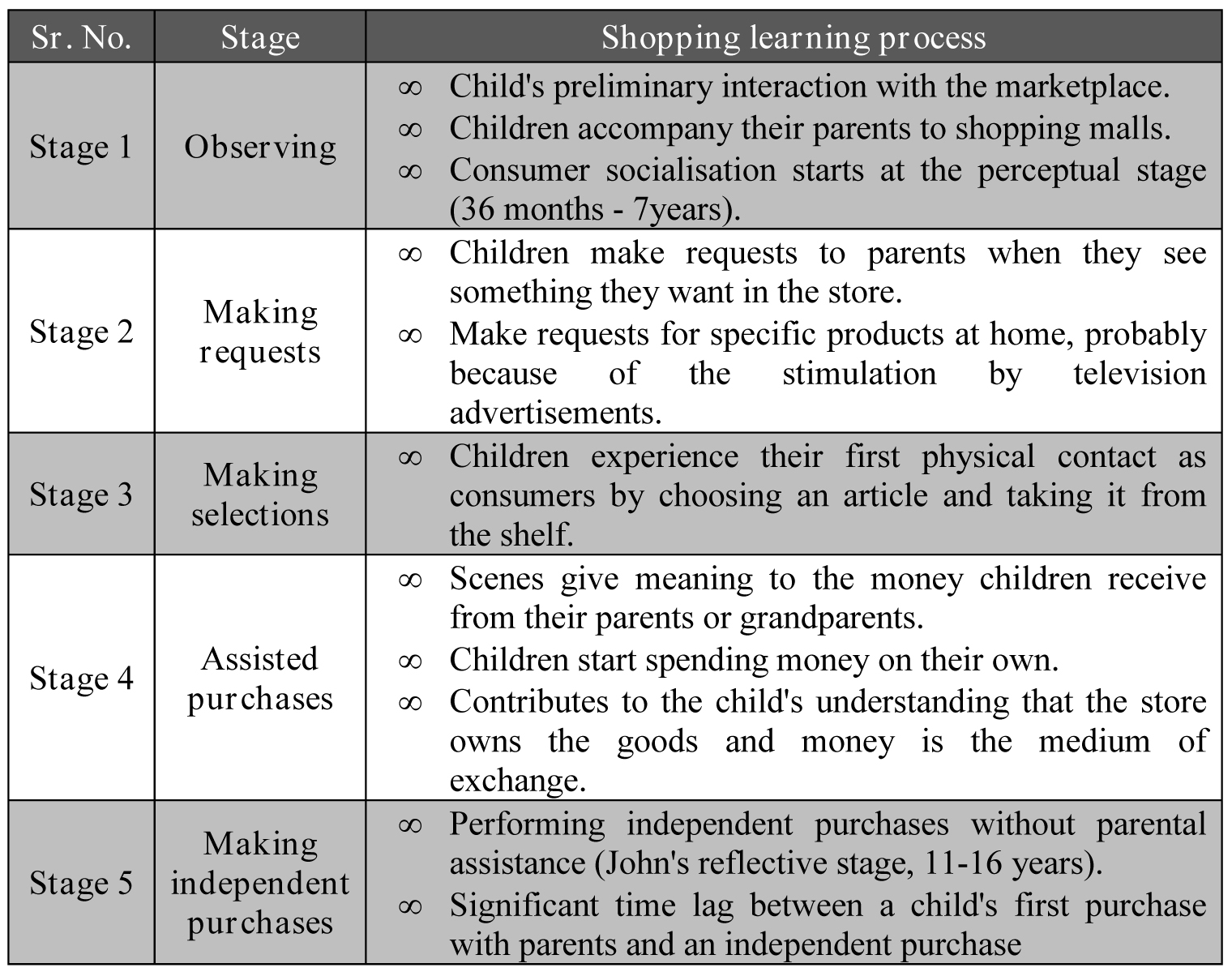

Table-1 : Children's five-stage shopping learning process in their consumer development (McNeal & Yeh, 1993).

Table-1 : Children's five-stage shopping learning process in their consumer development (McNeal & Yeh, 1993).

In a study Acuff (1997) reports that teenagers do not

consult their parents for buying candy and soft drinks in

most instances. The theory and published literature focus

largely on consumer socialisation in the childhood phase.

McGregor (1999) and Engel et al. (1995) emphasise,

however, that it should be recognised as a lifelong process.

Recent studies by consumer scientists observed other areas

of consumer socialisation, such as the socialisation of

consumers in a global marketplace, and the protection of

consumers in the electronic marketplace (McGregor, 1999);

consumer complaint behaviour in the children's wear

market (Norum & Scrogin, 1996); and the factors that

influence the food choices of children between the ages of

9 and 17 years (Hamilton et al, 2000). No attention was

given to the role of the media and parents as socialisation

agents in these latter studies. McNeal (1973) reviews the

value of and the reason for the need to study the consumer

socialisation of children as follows: "Much consumer

behaviour is performed under the influence of others. The

very foundation of human behaviour is learning from

others." At the same time McGregor (1999) states that

consumer socialisation is a function of, inter alia, the age of

the child, the content that is learned, and agents of

socialisation in the market.

Consumer Socialisation Agents

The studies on consumer socialization have got enough

importance since the era of world War II. In early stage

pioneers like Guest, McNeal, Berey and Pollay (John, 1999)

began to examine factors related to the consumer

behaviour of children. The topics investigated include

children's understanding of marketing and retail

functions, brand loyalty and the influence of children in

family decision making. In the case of children again the

studies are limited. Socialisation agents are the persons and

organisations involved in the orientation and education of

children as consumers. Some examples would be family

members, peers, the mass media, schools and retailers

(John, 1999).

Research in the field of the consumer socialisation process

of children gained momentum in the mid-1970s (John,

1999). Scott Ward's (1974) article entitled "Consumer

socialisation" which was published in the Journal of

Consumer Research, forcefully argued for studying

children and their socialisation into the consumer role. This

gave a lead to a new generation of researchers, and in

particular directed their attention to the role of socialisation

agents in children's development as consumers. Of

particular importance to this review are the studies that

focused on children's knowledge of consumer issues, and

the influence of the family and the media (as socialisation

agents) on children's development as consumers. The

family can be regarded as the primary source (agent) of

consumer socialisation. Extensive research has been

conducted on the role of the family as a consumer

socialisation agent over the past three decades (John, 1999;

Carlson & Grossbart, 1994; Hempel, 1974). Hawkins et al.

(2001) states that parents teach their children consumer

skills both deliberately and casually through instrumental

training, modelling and mediation. Instrumental training

occurs, for example, when a parent tries to teach a child to

eat a certain snack because it has nutritional value.

Modelling occurs when a child learns appropriate (or

inappropriate) consumption behaviours by observing

others (for example parents who smoke). Mediation occurs

when a parent alters a child's initial interpretation or

response to a marketing stimulus (for example an

advertisement depicting a situation in which a child will be

rewarded with a snack for good behaviour). Special

emphasis is placed on children's perceptions about the

influence of promotional activities of television

advertisements on their buying behaviour.

Marketing Activities targeted at children

The marketers design their marketing activities in such manner which attracts the consumers. Children in particular have an immature mind with respect to buying, which cannot have discretions about the nature of the material they are subjected to, through mass media advertisements. Majority of the said category instantly form an opinion about what they see, mostly in favour of it. This is a fast decision domain, where the exposures to mass media these youngsters enjoy, are on a high degree. The children are easy target to advertisers in such manner. The tendency of attracting towards the informations shown on TV or other media is common among children. Children are also easy to fall prey to their choicest advertisements being aired on media. Marketers see potential market in children. They treat children not only as primary market, but as influencers and the future market. They have very deliberately entered the schools. They put up posters and billboards in the schools, persuading the cash-starved schools into opening their doors to them by paying for access to classrooms and space for their advertising material and promotions. Webbased groups providing free e-mail accounts and contests with tempting prizes is another strategy that is rampantly used. This almost approximates to a crime because it is nothing less than attacking the natural credulity of the most innocent, most gullible and most inexperienced beings on earth.

Strategic use of 'Pester Power' by children

Every day crying of children like-Mom I want this, Dad I want this” are the demands, fuelled by marketing tactics that corrode the adult wallets. The marketers are relying on the children to pester the mom to buy the product, rather than going straight to the mom. Children rule, be they in terms of what to watch over TV or what to buy for themselves or what a household buys. The influence that the children wield over purchase decisions in a household along with the nagging effect that they have on their parents is growing day by day. With the increase in the number of working couples, their pester power is inversely proportionate to the time available with parents. Their day begins with Tom and Jerry and ends with Dexter. There is an untiring wish list of food, fun, collectibles, gadgets and brands. The influx of niche channels especially designed for children like the Cartoon Network, Hungama and Toonami has given a big push to the pester power in India. According to some estimates, in 2005, there were more than 120 million tween (children between 8-12 years of age). Among them around 45 million live in urban areas who have the power of determining or influencing the whopping Rs. 20,000 crore worth purchasing decisions on food, mobile phones, apparel, cars and FMCGs. This offers a big temptation to the marketers to treat the pre-adolescents as mature and independent customers and creating a peter power. Using this strategy, they have been successful in making parents almost redundant in purchase decision.

Children's Eating Habit and Role of Advertising in Promoting Food Choices

The eating habits developed in childhood develops food

preferences for the whole life if not completely then

definitely some of the habits are carried forward in

adulthood. Children market remains crucially important

as the marketers seek to attract a new audience and build

brand loyalty at a very young age. The advertisements

have created very powerful and vocal kid consumers with

huge buying leverage. In a compilation of studies done on

children's media habits has deduced that children under

eight are unable to critically comprehend televised

advertising messages and are prone to accept advertiser

messages as truthful, accurate and unbiased, leading to

unhealthy eating habits.

It is claimed that consumer preferences can be

manipulated through advertising. Clearly advertising

tends to affect knowledge, preferences and behaviour of its

target market since that is the reason for doing it

(Linvingstone, 2004).

Advertising could influence eating habits for young

children (Hastings & al., 2003). The logic behind any

advertising is quite simple: it tries to “meet consumer

needs and create new ones”. In 2007, the first-hand

information acquired by consumers and then used as a

shortcut in subsequent decision making – explanation

added) by advertising a family friendly environment and

generating positive associations that may attract

consumers. Children have many sources though which

they are gaining knowledge about food product. The TV,

Internet, Newspaper, other mode of classical advertising

are common source of informations.

Food promotion to children

The concern of health with food products consumptions

and its impact of children's health have always been seen

as an issue. Zuppa, Morton and Mehta suggest that the

amount of advertising to which children are exposed “has

the potential to influence children's health attitudes and

behaviours. Television may be more influential than

families in setting children's food preferences” Epstein et

al (1995) clarify the link by identifying a co-relation, but not

causation between television viewing and obesity. There

has been significant impact on the health of children due to

over eating, consumption of unhealthy food. There has

been concern over the harmful effects of food promotion to

children. High levels of concern currently centre on the

evidence of rising obesity among children, in common

with many other countries in the developed world (World

Health Organization, 2000). Previous food-related

concerns have included nutrition, dental health, dieting

and anorexia, and so forth. The royal college of physicians

has reported that the obesity among the children is

increasing (Kopelman, 2004 & Ambler, 2004). All agrees

that the food industry is one of the major player in the field

of advertising (Hastings et al 2003, Young, Paliwoda &

Crawford, 2003). Studies show that food advertising on

television is dominated by breakfast cereals,

confectionary, savory snacks and soft drinks, with fast

food restaurants taking up an increasing proportion of

advertising on television.

A major review of the field, recently conducted by

Hastings et al (2003) for the food standards agency, has

focused academic, policy and public attention on the role

that food promotion, particularly television advertising,

plays in influencing children's food choices, defined in

terms of food knowledge, preferences and behavior. Both

research methods and findings addressed in this and other

reviews are much contested (Paliwoda & Crawford, 2004;

Young, 2003; Ambler, 2004; and Livingstone, 2004) some

reviews cover a wide terrain, examining the range of

factors which may influence children's diet. Others are

focusing on the direct effects of advertising on food choice.

Unfortunately, much of the literature on diet and obesity

pays little attention to media related factors such as

exposure to television in general or advertising in

particular. Also unfortunately, much of the literature on

the effects of advertising pays little attention to the

contextual factors which may mediate or provide

alternative explanations for the observed relationship

between media use and children's diet and/or weight.

Reviewing the field is complex in part because the

research available spans a range of academic disciplines,

countries and contexts and also because empirical studies

use different measures, control for different factors or omit

valuable information. In reviewing the published

literature, it is worth identifying not only what can be

concluded but also what remains unclear as well as

questions for future investigation. Importantly, the

balance of evidence (experimental, correlation and

observational) in the published literature shows that

television advertising has a modest, direct effect on

children's food choices. Although there remains much

scope for debate, this conclusion is widely accepted across

diverse positions and stakeholders (Livingstone, 2004).

Food promotion is having an effect, particularly on

children's preferences, purchase behavior and

consumption. This effect is independent of other factors

and operates at both a brand and category level' (Hastings

et al, 2003). Lewis and Hill (1998) conducted a content

analysis showing that food is the most advertised product

category on children's television, and that confectionary,

cereals and savoury snacks are the most advertised.

Hence, 60% of food adverts to children are for convenience

foods, 6% for fast food outlets, and the remainder for

cereals and confectionery. Lewis and Hill (1998) in this

study they found that overweight children are less

satisfied with their appearance and have a greater

preference for thinness; feeling fat was directly related to

weight. In general, children feel better, less worried and

more liked after seeing adverts. They also found an

interaction effect: after seeing a food advertisement,

overweight children feel healthier and show a decreased

desire to eat sweets, while normal weight children feel less

healthy and more like eating sweets than before seeing the

ad. The opposite pattern was observed after viewing nonfood

ads. Hastings et al (2003), 'the foods we should eat

least are the most advertised, while the foods we should

eat most are the least advertised'. A recent survey of UK

parents conducted for the national family and parenting

institute (2004) shows that parents feel their children are

'bombarded' by advertising to ever younger children and

across an ever-greater range of media Platforms. They

claim to be anxious, irritated and pressurized, not least

because of the considerable domestic conflicts they claim

that consumer demands from children result in within the

family. Young (2003) in his study he concluded that

children understand advertising from eight to nine years

old and that they play an active role in families' food

buying. Dietary preferences of children are said to be

established by about five years old, before advertising is

understood. The author further argues that a multiplicity

of factors, of which advertising/television viewing is only

one, influence eating patterns. Stratton & Bromley (1999) in

their study they determined through a series of interviews

that the dominant preoccupation of parents is to get their

children to eat enough. Parents try to adjust the food to the

preferences of family members so that children can eat.

There was a notable lack of reference to nutrition and

health when talking about food choices for children in the

British families interviewed. There have been many

investigations determinant of children's diets, while

schools and peers are also influential in determining

preferences and habits.

A study in New Zealand, Hill, Casswell, Maskill, Jones &

Wyllie (1998) showed that although teenagers had good

knowledge of what was healthy and what not, what they

ate was determined by how desirable foods were. This is

really significant to develop the strong eating habits at the

earlier stage of the life; if this pattern of eating habits would

be continued in mature life and hard to change at a later

stage of the life (Hill, Casswell, Maskill, Jones & Wyllie,

1998; Kelder, Perry & Klepp, 1994; Sweeting et al, 1994).

Numerous studies pointed out the fact that those who eat

with the family have healthier dietary habits. Family meals

become less frequent as children get older and the

frequency of those meals differ for different ethnic groups

and socio-economic status (Neumark & Sztainer, Hannan,

Story, Croll & Perry, 2003). The influence of family eating

patterns on dietary intake stays strong even after

controlling for other variables such as television viewing

and physical activity. Eating away from home also

increases the consumption of soft drinks which is related to

problems with weight (French, Lin et al, 2003).

Conclusion

The study confirms that it is a challenging task to research children. Marketers and researchers who wish to control the buying button "inside children's heads" should note that today's children are completely different from children of, say, ten years ago. Children are now technosavvy and more knowledgeable. They have increased access to information and have a greater knowledge and understanding of today's issues. They are truly the Internet generation, and get their news and information primarily from television. The recent trends have increase the interest of the marketers in child consumers. One of them is the discretionary income of children and their power to influence parent purchase. The other very significant development is the enormous increase in the number of available channels and thus created a growing media space just for children and children products. They understand the marketing and advertising campaigns presented to them. They are, however, rooted to home - their family is still their most important social group. The television advertisements open up many opportunities for parents to educate their children on matters relating to marketing and other consumer issues.

Further Scope of study:

This study stresses the need for future empirical research on children's consumer behaviour to be conducted in the Indian context. For example, the role of salespeople in the retail environment and the school as socialisation agents could fruitfully be studied. The literature study revealed that not a single study has been conducted to date in India to investigate the role of retailers in educating young consumers. The positive assistance given by the secondary school sector in this research should be utilised by marketing and consumer science researchers in order to add new insights to the existing body of knowledge in this vibrant field. Understanding how children become socialised to function as consumers is important not only from a managerial or marketing perspective, but also from a societal, technological and cultural perspective where issues such as single-parent families, drug abuse and the Internet require the attention of researchers. Future research could also focus on gender-role orientation and cross-cultural marketing aspects regarding the consumer socialisation which influences the food buying behaviour of children.

References :

- Acuff, D. 1997. What kids buy and why: the psychology of marketing to kids. New York. Free Press.

- Ambler, T., Braeutigam, S., Stins, J., Rose, S. and Swithenby, S. (2004). Salience and choice: Neural correlates of shopping decisions. Psychology and Marketing, 21: 247–261.

- Blackwell, R, Miniard, P & Engel, J. 2001. Consumer Behaviour. 9th ed. New York. Harcourt.

- Cardwell-Gardner, T & Bennett, J.A. 1999. Television advertising to young children: an exploratory study. Proceedings of the 1999 IMM Marketing Educators Conference, September 1999.

- Carlson, L & Grossbart, S. 1994. Family communication patterns and marketplace motivations, attitudes, and behaviours of children and mothers. Journal of Consumer Affairs 28(1): 25-54.

- Carlson, L, Laczniak, R & Walsh, A. 2001. Socializing children about television: an intergenerational study. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science 29(3): 276-288.

- French, S. A., Lin, B. H., and Guthrie, J. F. (2003). National trends in soft drink consumption among children and adolescents age 6 to 17 years: Prevalence, amounts, and sources, 1977/1978 to 1994/1888. Journal of the American Dietetic Association, 103(10), 1326- 1331.

- Gorn, G & Florsheim, R. 1985. The effects of commercials for adult products on children. Journal of Consumer Research (11),962-967.

- Hastings, Gerard, Martine Stead, Laura McDermott, Alasdair Forsyth, Anne Marie MacKintosh, Mike Rayner, Christine Godfrey, Martin Caraher and Kathryn Angus. (2003a). Review of research on the effects of food promotion to children. Final report, prepared for the Food Standards Agency, 22nd September, 2003.

- Hastings, Gerard. (2003). Social marketers of the world unite; you have nothing to lose but your shame. SMQ, 9(4), 14-21

- Hawkins, D, Best, R & Coney, K. 2001. Consumer Behaviour. Building Marketing Strategy. 8th ed. Boston. McGraw-Hill. lHempel, D. 1974. Family buying decisions: a crosscultural perspective. Journal of Marketing Research 10:295-302.

- Hill, L., Casswell, S., Maskill, C., Jones, S., & Wyllie, A. (1998). Fruit and vegetables as adolescent food choices.Health Promotion International, 13(4), 55-65.

- John, D.R. 1999. Consumer socialization of children: a retrospective look at 25 years of research. Journal of Consumer Research 26(3): 183-237.

- Kelder S. H, C L Perry, K I Klepp and L L Lytle. (1994). Longitudinal tracking of adolescent smoking, physical activity, and food choice behaviors. American Journal of Public Health, 84(7), 1121-1126.

- Kopelman. (2004). cited in Ambler, T. (2004). Does the UK promotion of food and drink to children contribute to their obesity? (Centre for marketing working paper No. 04- 901). London: London Business School.

- Lewis, M. K., and Hill, A. J. (1998). Food advertising on British children's television: A content analysis and experimental study with nine-year olds. International Journal of Obesity, 22(3), 206-214.

- Livingstone, Sonia (2004). Advertising Foods to Children: Understanding Promotion In The Context Of Children's Daily Lives [online]. London: LSE Research Online.http://www.lse.ac.uk/collections/media@lse / Dated: 12-11-2013.

- Macklin, C. 1987. Preschoolers' understanding of the informational function of television advertising. Journal of Consumer Research 14: 229-239.

- Mc Gregor, S. 1999. Socializing consumers in a global marketplace. Journal of Consumer Studies and Home Economics 23(1): 37-45.

- Mc Neal, JU & Yeh, C. 1993. A cross-cultural study of children's consumer socialization in Hong Kong, New Zealand, Taiwan, and the United Nations. Asia Pacific Journal of Marketing and Logistics 5(3): 56-69.

- McNeal, JU. 1973. An Introduction to Consumer Behaviour. New York. Wiley.

- Mc Neal, JU. 1993. Born to shop. Children's shopping patterns. American Demographics 15(6): 34-39.

- Mc Neal, JU.& JI, M. 1999. Chinese children as consumers: an analysis of their product information sources. Journal of Consumer Marketing 16(4): 345-364.

- Meyer, T. 1987. How black children see TV commercials. Journal of Advertising Research 18:51-85.

- Mishra.H.G,& Singh.S.(2012) Due to Television Commercial, Change in Eating Habits and its Direct Impact on Obesity of Teenager of Jammu;The Public Administration and Social Policies Review IV Year, No. 1(8).

- Neumark-Sztainer, D., Hannan, P. J., Story, M., Croll, J., and Perry, C. (2003). Family meal patterns: Associations with sociodemogpaphic characteristics and improved dietary intake among adolescents. Journal of the American Dietetic Association, 103(3), 317-322.

- Norum, P & Scrogin, J. 1996. Consumer complaint behaviourin the children's wear market in the US. Journal of Consumer Studies and Home Economics 20:363-375.

- Paliwoda, Stan and Ian Crawford. (2003). An Analysis of the Hastings Review: The Effects of Food Promotion on Children. Report prepared for the Food Advertising Unit, December (2003).

- Roedder, D. 1981. Age differences in children's responses to television advertising. Journal of Marketing Research (8),144-153.

- Sheth, J, Mittal, B & Newman, B. 1999. Customer behavior: consumer behavior and beyond. New York. Dryden Press.

- Soni.S & Upadhyaya.M(2007). Pester Power Effect of Advertising; International Marketing Conference on Marketing & Society, 8-10 April, 2007, IIMK 441.

- Stratton, P., & Bromley, K. (1999). Families Accounts of the Causal Processes in Food Choice. Appetite. 33(2),89-108.

- Sweeting, H., Anderson, A., and West, P. (1994). Sociodemographic Correlates of Dietary Habits in Mid to Late Adolescence. European Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 48(10), 736-748.

- Ward, S. 1974. Consumer socialization. Journal of Consumer Research 1 (September): 1-14.

- Yavas, U & Abdul-Gader, A. 1993. Impact of TV commercials on Saudi children's purchase behaviour. Marketing Intelligence and Planning 11(2),37-43.

- Young, Brian (2003) Advertising and Food Choice in Children: A Review of the Literature. Report prepared for the Food Advertising Unit, August (2003).