Subscribe now to get notified about IU Jharkhand journal updates!

The Demographic Trends and the Relevance for Active Ageing in Kerala An Analysis from Lifelong Learning Perspectives

Abstract :

Demographic changes are seen as most important factor for policy making in all the nations. Ageing population becomes the most important policy concern in the national policy makings nowadays. This is because of the reason that the ageing population is expected to grow in a faster rate as socio-economic and cultural factors have positively contributed to the well being. Kerala has reached be low replacement level and no has a different trend in demographic transition. Though the state has achieved high literacy rate, highlife expectancy rate, low birth rate etc.,which are comparable to the developed countries, the state now faces the problem of ageing population. Health and security are the traditional methods to face the challenges of ageing. Participation has become an important tool for active ageing and lifelong learning as crucial for preparing people at all ages to be active and skilled. This paper seeks to understand the relevance of lifelong learning as a better tool for active ageing and to face the challenges paused by ageing population in Kerala.

Keywords :

Demographic, Ageing Population, Socio-economic, Cultural Factors, Lifelong Learning,I. Introduction

21st Century was knows as the Century of the Elderly and 22nd Century will manifest as the period of 'ageing of the aged'. (HelpAge India, 2014). Between 2015 and 2050, the proportion of the world's population over 60 years will nearly double from 12% to 22% and by 2050, 80% of older people will be living in low- and middle-income countries (World Health Organization, 2021). It has become evident that the trends in demographic changes are seen as most important factor for policy making in all the nations. Ageing population becomes the most important policy concern in the national policy makings nowadays. This is because of the reason that the ageing population is expected to grow in a faster rate as socio-economic and cultural factors have positively contributed to the well-being. But it is a fact that there are differences in priorities given to the care for ageing population in various countries. WHO emphasizes that the

olicies and programs should be formulated on the basis of the rights, needs, preferences and capacities of older people and those policies have to recognize the important influence of earlier life experiences on the way individuals grow old.

India's population is currently growing at 1.0 percent per annum and the statistics shares that there is a gradual deceleration of population which is evident in almost all states in the country. Several studies (Irudaya Rajan and Zachariah, 1997; Tharakan and Navaneetham, 1999; Irudaya Rajan, 2000) states that the low level of fertility has resulted remarkable progress in demographic transition in most of the south Indian states. Kerala, the southern state of India, has reached below replacement level and now has a different trend in demographic transition. Though the state has achieved high literacy rate, high life expectancy rate, low birth rate etc., which are comparable to the developed countries, the state now faces the problem of ageing population like the developed countries. According to the Kerala state ageing policy, the growth of elderly (60+) is increasing in a faster rate. During 1961, the aged population constituted only 5.9% of the total population in Kerala. It increased to 6.2% in 1971, 7.5% in 1981, 8.8% in 1991 and to 10.5 % in 2001. As per 2001 Census, the total number of old age persons was 33.36 million (Kerala Economic Review, 2007) and 2011 Census states that one in eight persons in Kerala were found to be 60 and above (MoSP, 2021).

In both developed and developing countries, the ageing population raises several socio- economic concerns. One of the important problems faced by the developed world is the shrinking of labour force. Together with the labour shortage, they have to consider the health and care and pension policies. Developing countries also face financial problems when they have to formulate health and care policies. Pension schemes are also a great concern for policy makers in developing countries. The WHO (2002) points out that 'the ageing of the population is a global phenomenon that demands international, national, regional and local action'. The Active Ageing policy framework of the WHO proposes three main areas as most significant such as health, participation and security. Health and security are the traditional methods to face the challenges of ageing. Participation has become an important tool for active ageing and lifelong learning as crucial for preparing people at all ages to be active and skilled.

Developing countries are also facing the challenges brought by ageing population almost in the same way as confronted by the developed countries. But there are differences in the priorities given to each sectors. Health and security measures are promptly taken in favor for the elderly but there are no policies with regard to participation, which is considered as important for active ageing. The state of Kerala in India is facing more challenges due to the reversal of the demographic trends. In the coming years, according to Irudaya Rajan and Zachariah (1997), 'the major socio- economic problems would be finding gainful employment for the older working age population, maintenance of the health and nutrition of the elderly, and providing them with means of subsistence through social security and pension, etc.'. The maintenance of health and care and security and pension, the state needs a strong economic basis. But the financial status of the Kerala is not strong to maintain the social security of the ageing population (Kerala State Ageing Policy, 2006). At the same time the policy recommendations has not given importance for the participation of the elderly in the socio-economic development of the society. In this paper, I wish to argue that lifelong learning as an integrated programme for people at all ages to be self-sufficient and to take part in social and economic transformation.

This paper seeks to understand the relevance of lifelong learning as a better tool for active ageing and to face the challenges paused by ageing population in Kerala. In the first part, a discussion is carried out on lifelong learning in an international perspective and to evaluate the underpinning idea behind lifelong learning discourse. The discussion wish to state that lifelong learning is considered as a better programme to face the challenges faced by ageing population. Since the state of Kerala is taken as a case, in the second part of the paper, I wish to discuss the status of Kerala in the national and international scenario. In the third part of the paper, the importance of lifelong learning is discussed considering the policy recommendations of Kerala State policies on ageing.

2. Lifelong Learning from an International Perspective

Education has become a major component of human resource development and is a basic factor for social and economic development. Quality and skill of the human resource is properly catered through the provisions of education, literacy and other social development activities. But the widespread influences of the global forces hav

changed the social, economic, political and educational policy development. In the educational field, there has been a tremendous development of international market for education and learning. This has necessitated the formation of different concept to learning. One of the important contributions of international organizations was the concept of lifelong learning. Most of the developed countries have accepted lifelong learning as a better way to face the changing nature of the labour force. The concept of lifelong learning became very relevant due to demographic changes in all over the world during these decades.

Human beings have to learn throughout the life since the speed of change in society has increased. There are differences in learning in the earlier times and today (Jarvis, 1995). The present age is far ahead than the former times. Therefore, the time forces everyone to learn throughout life. Though the process and the content are same for literacy, education and learning, there are differences in the meaning and use of these terms. According to Richmond, et.al (2008), 'literacy is a process, not an end-point. It is rather the entry point to basic education and the passport to lifelong learning. Literacy is a necessary part of using new technologies, learning new languages, taking on new responsibilities and adapting to a changing workplace'. The concept of literacy has different dimension in policy analysis of various countries. In India, according to National Literacy Mission, functional literacy implies 'Self-reliance in 3 Rs' (Reading, Writing and Numeracy). It is also interesting to note that it is imparted to the illiterate people in the age group of 15-35. Education, on the other hand, is used commonly to the education of children. Learning, on the other hand, is an ongoing process throughout the life of an individual.

Whether they do so consciously or not, human beings keep on learning and training themselves throughout their lives, above all through the influence of the surrounding environment and through the experiences which mould their behaviour, their conceptions of life and the content of their knowledge. Hundreds of million of adult need education, not only for the pleasure of perfecting their capacities or contribution to their own development, as before, but because the demands for over-all social, economic and cultural development of current century societies' require the maximum potential of an educated citizenry (Faure, et.al, 1972).

There are different opinion regarding lifelong learning and lifelong education, which provides confusing ideas on education and learning. But according to scholars, education is much narrower than learning. Hence lifelong education debases education (Lawson cited by Hager, 1998). Wain (cited by Hager, 1998) also suggest that lifelong education is a process in all kinds of learning which can affect the individual growth

,

i.e. formal, non-formal and informal learning and the interest in on how to enhance the education of learners. There is an interrelation between education and learning as related to process to product. Policy makers and scholars consider lifelong education as a process and lifelong learning as a product. Apps (in Hager, 1998) defines learning as "internal changes that occur in our consciousness", i.e. as a product and education as "those activities, events and conditions that encourage learning", i.e. as a process. Hence, lifelong learning becomes "those changes in conciousness that occur within us throughout our lifetime" and lifelong education becomes "those opportunities both deliberate and unintentional that influence learning that take place". These arguments suggest that lifelong learning is all those learning activities that are taking place in an individual's lifetime.

Lifelong learning is not a new concept. In the earlier times, the discourse has more of a focus on lifelong education than lifelong learning. The idea of lifelong learning and the related concept of lifelong education have its origin in the early twentieth century which can be traced in the writings of Dewy and others (Jarvis, 1995). The concept of lifelong education came to major prominence in the later 1960s when it was proposed by both UNESCO ("lifelong learning") and the Council of Europe ("education permanente") as the master concept for ensuring educational opportunities which were spread over the whole of a person's lifetime (Hager, 1998). The discourse on the concept of lifelong learning proposes an approach in education across the board rather than by a specific sector or through a particular curriculum. This idea points out that institutionalized education can no longer claim a monopoly over knowledge production and assessment. Considering as a policy or mode of provision, lifelong learning create a view of considering learning as a process over lifetime without boundaries. Lifelong learning can be understood in relation to certain contemporary social practices- lifestyle, vocational and critical (Usher cited by Edwards and Usher, 2001).

The OECD, in its several articles emphasized the role for education for the economic growth and through this, an increase in general well-being. During the 1960s, human capital theorists pointed out a strong link between investments in education and economic growth for both individuals and countries. Economists argued for the necessity of investing in education and training in response to the challenges brought by the technological advancements (Denison and Schultz in Rubenson, 2006). Keynesian political economic paradigm at that time moulded the idea that efficiency and equality through investment in education was vital for human capital. OECD found the idea as fundamental for the socio-economic development and became the prophet for of this doctrine, which in fact inspired many countries to develop strategies to expand education in the name of economic prosperity. Towards the end of 1960s, there were strong indication that the labour market could not fully absorb the over supplied graduates. This promoted OECD to think about the concept of recurrent education (Rubenson, 2006).

During the 1960s, UNESCO as a specialized agency of the United Nations was more concerned about the impact of educational crisis on individual, economic and social benefits. In response to these concerns, the International Commission on the Development of Education in 1970 pointed out that a system built for the education of children and youth would not be well suited to respond to the growing need. The commission found the education system as redundant and in response promoted the need for lifelong learning (Rubenson, 2006). At time of the slow economic growth in 1980s, OECD turned its attention to education as the generator of economic growth. To handle rapid increase of unemployment and uncertainty, OECD promoted the idea of lifelong learning. By 1996, OECD had embraced the notion that learning is not necessarily intentional and structured, nor that it takes place in formal or non-formal institutional settings. The idea that learning takes place throughout one's whole life fostered the concept of lifelong learning (Tuijnman and Brostròm in Rubenson, 2006).

The World Bank emphasized that lifelong learning is becoming a necessity in many countries and that opportunities for learning throughout one's lifetime are becoming critical for competitiveness in the knowledge economy. "Developing countries and countries with transition economies risk being further marginalized in a competitive global knowledge economy because their education and training systems are not

equipping learners with the skills they need. To respond to the problem, policymakers need to make fundamental changes. They need to replace the information-based, teacher-directed rote learning provided within a formal education system governed by directives with a new type of learning that emphasizes creating, applying, analyzing and synthesizing knowledge and engaging in collaborative learning throughout the lifespan" (World Bank, 2003, pp.18-19). According to the new educational approaches, learning is not just a question of developing resources and acquiring skills, it is also a process of acquiring and developing social, cultural and personal identity. The concept of learning instead of education implies that the learner and the educational institutions should see learning in the context of the whole life course and they should not be rooted in one area of learning only (Llleris and Rasmussen in Rasmussen, 2006). Since the learning is throughout the lifespan, all-round development of an individual must be acknowledged.

In today's knowledge society, an individual has to be informed and skilled. The changing socio-economic condition necessitates an individual to be adapted to the changing circumstances. 'To survive hyper-competition and volatile consumer choice, learning organizations and a workforce engaged in lifelong learning are needed' (Glastra, et.al, 2004). European Union has also given priority to lifelong learning with a view to activate the ageing population. 'There is a consensus of opinion that both the economic development worldwide and the strongly graying labour market in the EU prompt that a thorough and continuous improvement of the ability of the European labour force to act within the knowledge society will be the only negotiable way to maintain the European welfare states in the competition with Japan and the US' (Pedersen, 2004).

3. Lifelong Learning and its social and economic implications

Lifelong learning is considered and realized in different ways in different countries. Due to differences in socio-economic and cultural factors, the importance of lifelong learning gets more implication. According to Wilson (2001), lifelong learning is seen to be a key means for addressing the central issues like- ageing, community and economic change. In his paper, Wilson states that lifelong learning is seen as a kind of 'lifeline' (which means a vital means of communication) for Japan's 'maturing' society experiencing rapid social change. One of the greatest advantages of learning throughout

life is that one can learn new ideas and activities to face the changing nature of the society. The challenges of the new world order have its consequent advantages and disadvantages to all sections of people. Learning in such social order has paramount importance. According to Long (cited by Hager, 1998), there are three critical foundation of lifelong learning.

- Lifelong learning – A Basic Human Need

- Social and technological factors (these include the increasing failure of the 'front end' model of education)

- Institutional pressures (these include both "philosophical pressures" – education as a good in itself – and "practical pressures" – public demands placed on educational institutions).

According to Hager (1998) these pressures could conceivably produce range of outcomes and this can happen if the society has some provision on basic conditions. At one extreme, a minimalist view of lifelong education could be achieved if the society has adequate provision of adult education. The other extreme, a maximalist view of lifelong education seeks nothing less than a learning society. Learning societies can be one which favor democratic, where a "shared, pluralistic and participatory form of life" is practiced in Dewey's sense rather than a simple set of institutions and constitutional guarantees (Wain cited by Hager, 1998). One of the important benefits for learning is to ensure social and economic inclusion. When people are not informed and skilled they often are separated from the scene.

Education is drawing closer to sections of the population usually excluded from educational circuits, providing the system with new clients. The need is felt throughout the world for institutions aimed at special categories of adults, workers wanting qualifications, professional men, executives and technicians on whom political or social changes suddenly impose responsibilities for which they were not trained or which technological changes have superseded (Faure, et. al, 1972). Ecclestone (1999) is of the opinion that 'far from the hard-edged, arid economic instrumentalism of conservative policy, new discourse in lifelong learning emphasise social inclusion and people's ability to survive in a ruthless global economy. Attempts to make more learners participate in lifelong learning emphasise the need to prevent people from being

marginalized or from excluding themselves (Kennedy and Fryer in Ecclestone, 1999). Learning has become a lifelong commitment. People put others at risk if they do not 'learn' (Tuckett cited by Ecclestone, 1999). Learning is empowering, fun and voluntary and it (education) is personally and socially transforming.

Post-modern is part of the globalization of capitalist economic relations and the growth of postindustrial and consumer-oriented social formations within an information-rich environment enabled by new technologies (Harvey cited by Edwards and Usher, 2001). The post-modern approaches have provided, according to Edwards and Usher (2001), a space of a multiplicity and diversity of meanings and possibilities through which to make a sense of and engage with contemporary trends and processes, including those of lifelong learning. Lifelong learning has emerged as a potent way of framing policy and practice in many countries around the globe. Indeed, it may be thought of as one of many contemporary, global, "policy epidemics" in education (Levin cited by Edwards and Usher, 2001). These policies and practices have been diverse and in most countries are still in the process of development. Lifelong learning can be considered as a mean of responding to these social and economic developments.

Together with the socio-economic necessities, the changing perceptions of learning have its relevance in providing further learning. The name change to lifelong learning indicated a new emphasis on individuals as agents of their own learning. Creating a learning society, in which 'people can learn at any stage of life, can freely select and participate in opportunities for study, and can have the results of their learning appropriately evaluated' (Monbusho in Wilson, 2001), the idea of lifelong learning has become a social phenomena.

It promotes the idea that learning is something that can be engaged in at any time over the life span, and provide variety of routes to qualifications for those who left school without them. Jarvis (2006) has the opinion that learning is an intrinsic part of the process of living. He has defined lifelong learning as

The combination of processes throughout a lifetime whereby the whole person- body (genetic, physical and biological) and mind (knowledge, skills, attitudes, values, emotions, beliefs and senses)- experiences social situations, the perceived content of which is then transformed cognitively, emotively or practically (or through any combination) and integrated into the individual

person's biography resulting in a continually changing (or more experienced) person.

To fulfill the meaning of the individual life, learning provides access, participation and achievement in education and training to people of all ages and provides statuses in society. The aim is to help people get more out of life and to contribute more to it. In social life, people have different kinds of responsibilities, to themselves and towards society. Lack of information posits problems to tackle these duties and responsibilities. Elderly, who were once the part and parcel of social transformation, are not able to confront these challenges. Leaning when it becomes an activity throughout life prepares them to deal with these changes. Policy makers there have to understand this dismally and formulate inclusive programmes. 'This later learning requires many wide-ranging educational structures and cultural activities to be developed for adults. These, while existing for their own purposes, are also a pre-condition for reforming initial education. Lifelong education thereby becomes the instrument and expression of a circular relationship comprising all the forms, expressions and moments of the educative act'(Faure, et. al, 1972).

At present, the society faces the problem of generation gap. The young population keeps away from the old people through words and deeds. Education, through an integrated approach can solve the generation gap. Faure, et. al (1972) are of the opinion that 'an attempt has to made to give the schools roots in the surrounding social context, to draw it out of isolation and fit it into the community, not only in rural districts, but in the towns and urban centres too. In the same way at family level an attempt is being made to integrate parents directly into the school structure, to associate them with the design of education, especially in 'community schools' or 'schools for parents'. Bringing education closer to the society, on the one hand, will help people to understand the use of learning and children to understand the need of physical work, on the other side.

The above discussion on the implication of lifelong learning in socio-economic life of individuals implies that leaning de facto is imperative. Lifelong and life-wide learning is an endeavour which contributes to the well-being of the individual (in his or her family, local community and society) together with the paid employment or production. Since education is given in the early stages of life, learning in the later stage provides

opportunity to understand the changes in the society over the life-span. Understanding the society means to be prepared to live in it. The change is so rapid and individuals need to be skilled and informed. In this paper, I wish to argue that lifelong learning can be a used as a tool to provide skill and information to the individuals throughout their life.

4. The relevance of Lifelong Learning in Kerala

Kerala has been highly responsive to social, economic and political reforms for the last 40 years. Kerala's economic and social status is compared with international standards because of its widespread literacy, participatory democracy, land reforms etc. Community participation and community service are very high and social and political life in Kerala is also high. According to Franke, 'it is this vibrant civil society and the sense of optimism and community commitment that lie at the base of Kerala's high material quality of life indicators' (Franke, 2001). Even with low economic development, the state could achieve high status in social indicators. This picture has often remarked as a 'Kerala Model of Development' (Franke and Chasin, 1996) among academicians and policy makers. 'The state of Kerala has become an enigma to analysts of international development, social progress and peaceful social change in the Third World' (Parayil, 1996).

Kerala is located in the south-western corner of the Indian subcontinent. It occupies

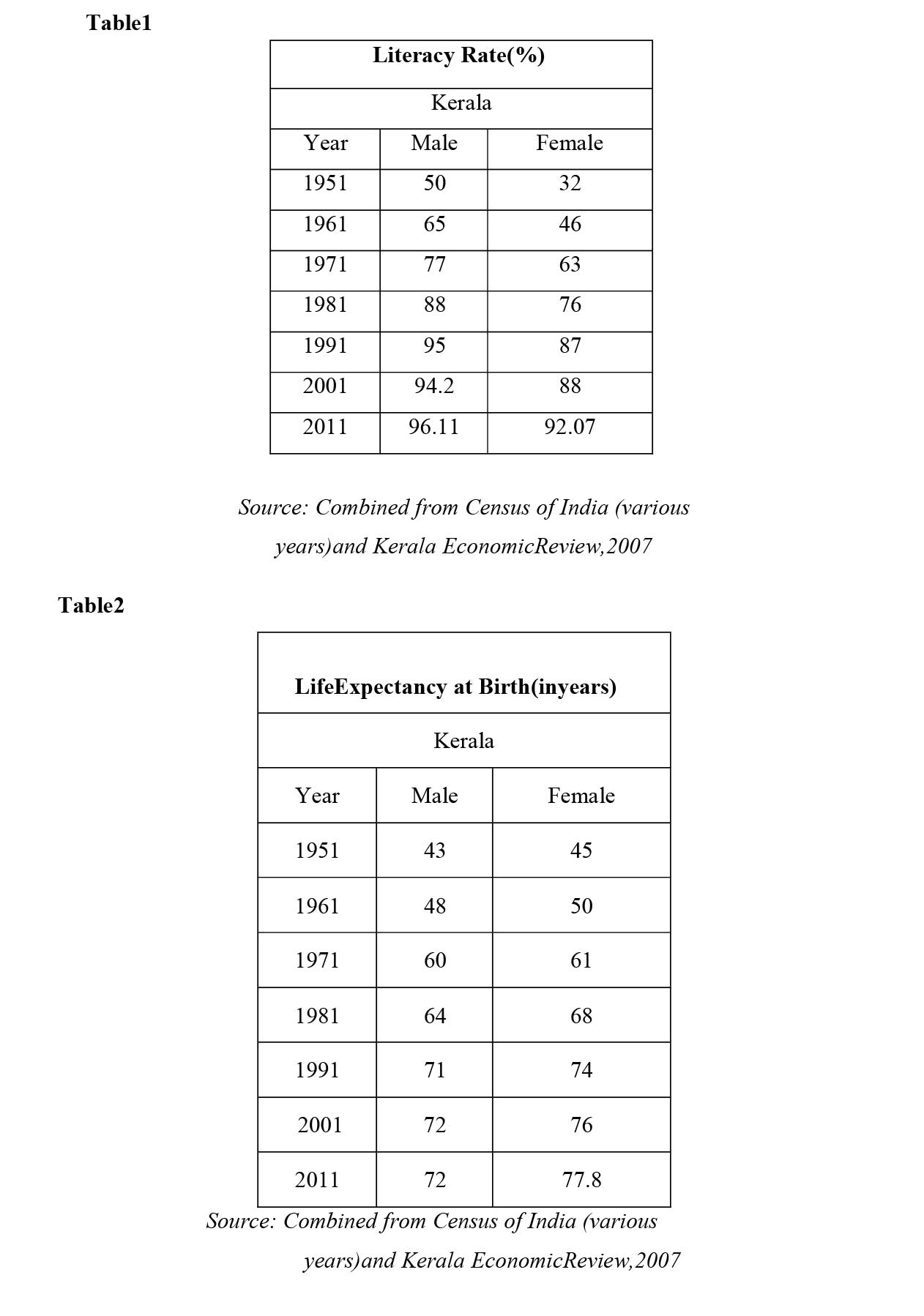

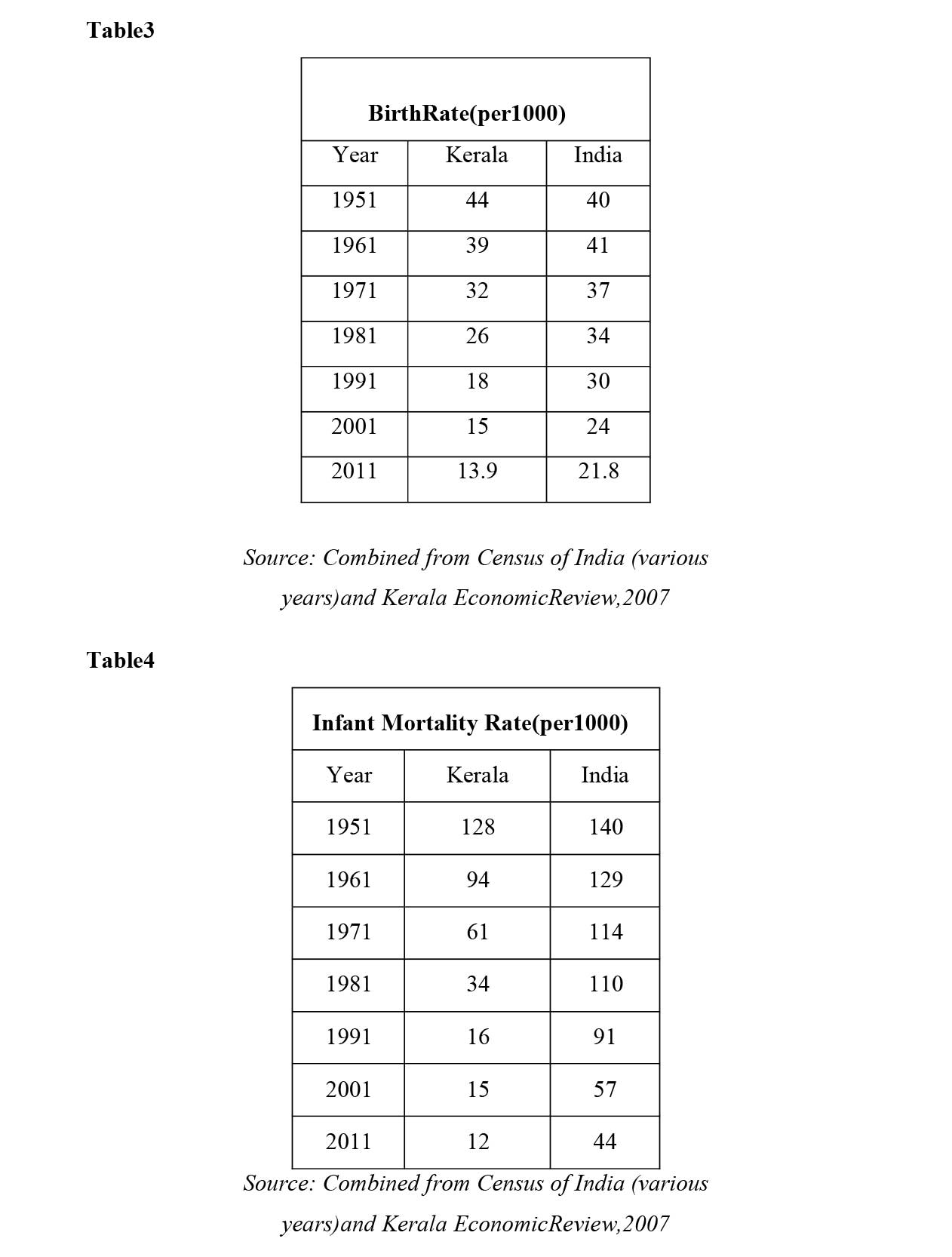

1.18 percent of the total land area of India with a population of 318.41 million consisting of 154.69 million males and 163.72 million females. Kerala's share in the population of India is 3.1 percent (Census, 2001). The state was formed in 1956 by combining the Malabar region of British constituted province of Madras and former princely states of Travancore and Cochin (Parayil, 1996; Chaudhuri and Harilal, 2004). When compared with the national averages, Kerala stands high in social indicators (Tables 1, 2, 3 and 4).

The tables above clearly show that Kerala has grown to a state where social and educational factors are high, even comparable to developed regions in the world. All these high achievements of social indicators made Kerala as an ideal state for the introduction of participatory local democracy. The lower differences in male-female and rural-urban literacy rates in Kerala enabled the citizens to make an informed decision and actively participate in local governance. High health status of people in Kerala

created a positive ground for introducing several projects with people's active participation. Kerala land reform was a great success and it transferred agricultural land from landlords to the tenants. This provision of lands helped the agricultural labourers for their house sites. One of the other factors for the smooth introduction of participatory democracy was the civic engagement. Kerala has powerful trade unions, agricultural labourers union, employee's organization, student, youth and women's associations. This clearly states that Kerala has is a learning society.

5. Emerging Ageing Scenario in Kerala

As Kerala is ahead of the rest of the country in fertility transition by 25 years, the ageing scenario is of particular interest (Irudaya Rajan, 2002). According to 2001 Census, the total number of old age persons was 33.36 million, constituting 10.5 % of the total population of Kerala (Kerala Economic Review, 2007). Kerala is the only one state in India which has graying population. This is very relevant to policy makers to formulate policies which will take proper measures to care the elderly. In 2006, the Kerala state formulated Old Age Policy in which it states that the government understands that the due to this drastic change, more importance needs to be given to the care of the elderly than for the child care.

According to the Old Age Policy, 90 per cent of old people are dependent on their sons and daughters. But due to migration of people and small family norms, they are being neglected at home. 26.55 percent are engaged in work among the elderly while 55.14 percent are dependents. 30 percent of them are below poverty line. 'According to the 1991 census, Kerala had 230,660 male pensioners and 77,660 female pensioners. Among them, 150,910 male pensioners and 51,190 female pensioners were aged 60 and above (Table 6). As the retirement age in Kerala is still 55 years, the number of pensioners in Kerala at present will be over 3 millions' (Irudaya Rajan, 2002). These pensioners are not the ones who receive social assistance in old age. To provide better health care and services, the state needs financial stability. The Old Age Policy states that the economy is not so strong to take care of the health and social care and pension services to all. The growing number of old ages homes in Kerala reveal the fact that old people are not properly cared.

The old people in Kerala are facing severe personal, social and economic challenges. They are neither not taken care by some one else nor able to take care of themselves. Here comes the necessity for participatory programmes as suggested by WHO. I would like to say that lifelong learning has to be introduced and given prominence in the state. As it is discussed earlier, the old people in Kerala can gain a lot from the lifelong learning activities. Lifelong learning that addresses current social issues has to be developed with a strong implication for social education in Kerala. Learning needs has to be based on the individual learner's needs. Since majority of old people are dependent, learning activities needs to focus on health care and service. 'Programs of information and education can change the elderly's knowledge, attitudes, and action to help ensure a healthy and productive old age' (Wolf, 2000).

One of the important problems that the old people in Kerala facing is that they are left alone at home. Due to migration of people to other countries for job and studies, old people are left at home or brought to old age homes. Old age homes in Kerala generally are not well organized and facilitated. According to the survey conducted by Irudaya Rajan (2002) it is found that 72% of old age homes had telephones, 65% had a library, 82% provided recreation facilities and 84% had a doctor to attend to the medical care of the inmates; only 18% of the old age homes owned a vehicle. Among the 125 old ages homes (which are privately managed), there are altogether 4170 elderly persons living. There are only 9 old age homes by the government, each of them accommodates about 100 persons. This indicates that there is less importance given to old persons. This can be avoided if provisions for learning are given to old people.

Since most of the old people are economically weak, they should be given training to get pat-time or voluntary works. This will enable them to be engaged with some works and take care of themselves. According to Wolf (2000) the elderly can be encouraged and trained to serve their own families as well as to undertake voluntary activities in the community. In particular, they can be taught the fundamentals of developmentally- oriented childcare for their own grandchildren as well as others. Learning opportunities provided to the elderly can cover all these areas—training in developmental child care, developing community activities for elderly handicapped and chronically ill, supporting young families in trouble, and acting in the political arena.

Lifelong learning for the elderly in Kerala is a new challenge to the policy makers. Since it has to be from the state level, it is a politically important issue. Since scholars and policy makers have not consider ageing as an opportunity (according to WHO), it is difficult to introduce lifelong leaning at this present scenario. But there is no other way to protect the elderly. So this paper has tried to argue that lifelong learning as imperative to make ageing as an opportunity for the state of Kerala.

6. Conclusion

In this paper I have discussed the relevance of lifelong learning in the context of ageing in Kerala. The background of this paper is on the World Health Organization's proposal for lifelong learning for the active ageing. To understand the origin and relevance of lifelong learning, a discussion on different perspectives are carried out. Opinions of international organizations like UNESCO, OECD and World Bank are analyzed. In India the term lifelong learning is a new concept. According to WHO and scholars, lifelong learning is an important tool for active ageing and a participatory method for old people. I have tried to put this view in the case of Kerala, which has now the ageing population. I my opinion lifelong learning will be effective at this stage and will help the old people to be more active and responsible for their health and safety.

References

- Arifin, E.N (2006), 'Growing Old in Asis: Declining Labour Supply, Living Arrangements and Active Ageing', Asia-Pacific Population Journal, December, pp.17- 30.

- Census of India 1991, 2001, Office of the Registrar General, Government of India Publication, New Delhi, www.censusindia.gov.in

- Chaudhuri, S, Harilal, K.N and Heller, P (2004): 'Does Decentralization Make a Difference? A Study of the People's Campaign for Decentralized Planning in the Indian State of Kerala, Centre for Development Studies, Thiruvananthapuram.

- Ecclestone, K (1999) 'Care or Control? : Defining Learners' Need for Lifelong Learning', British Journal of Educational Studies, Vol.47, No.4, December, pp.332-347

- Economic Review, Kerala State Planning Board, http://www.keralaplanningboard.org/

- Edwards, R and Usher, R (2001) 'Lifelong Learning: A Postmodern Condition of Education? , Adult Education Quarterly, 51, 273- 287

- Faure, E, et.al (1972) 'Learning To Be- The World of Education, today and tomorrow', UNESCO, Paris

- Franke, R.W (2001) 'Fueling Economic Growth Through Democratic Participation: Three Lessons from Kerala', Chautauqua Institution Lecture Series, Week Seven, Montclair State University, August 10

- Franke, R.W and Chasin, B.H (1996) 'Is the Kerala Model Sustainable? Lessons from the Past', Proposed for presentation at the International Conference on Kerala's Development Experience: National and Global Dimensions, 9-11 December, Institute of Social Sciences, New Delhi

- Glastra, F J , Hake, B J and Schedler, P E (2004) 'Lifelong Leaning as Transitional Learning', Adult Education Quarterly, Vol.54, No.4, 291-307

- Hager, P (1998) 'Lifelong Education: From Conflict to Consensus?', Studies in Philosophy and Education, 17: 323-332

- HelpAge India. 2014. State of Elderly in India 2014. https://www.helpageindia.org/wp- content/themes/ helpageindia/pdf/state-elderly-india-2014.pdf

- Irudaya Rajan, S and Zachariah, K C (1997) 'Long Term Implications of Low Fertility in Kerala', Working Paper, Centre for Development Studies, Thiruvananthapuram, Kerala, India.

- Irudaya Rajan, S (2000) 'Home Away from Home: A Survey of Old Age Homes and Inmates in Kerala', Working Paper No. 306, Centre for Development Studies, Thiruvananthapuram, Kerala, India.

- Irudaya Rajan, S (2002) 'Home Away from Home: A Survey of Old Age Homes and Inmates in Kerala, India', Journal of Housing for the Elderly, Vol.16, No.1-2, pp.125- 150

- Jarvis, P (1995) Adult and Continuing Education-Theory and Practice, Routledge, London

- Jarvis, P (2006) 'Towards a Comprehensive Theory of Human Leaning', Routledge, London

- Kaneci, D (2007) 'Active Ageing: the EU Policy Response to the Challenges of Population Ageing', IUIES, International University Institute of European Studies, University of Trieste, Gorizia branch. Paper No.8, September. http://eng.newwelfare.org/?p=237

- Kerala State Old Age Policy (2006), Social Welfare Department, Information and Public Relations, Department, Kerala State, http://www.kerala.gov.in/

- Ministry of Statistics and Program Implementation (2021), Situation Analysis of Elderly in India

- National Literacy Mission- India, http://www.nlm.nic.in/

- Parayil, G (1996), 'The Kerala Model of Development: Development and Sustainability in the Third World', Third World Quarterly, Vol.17, No.5, pp 941-957

- Rasmussen, P (2006) 'Globalization and Lifelong Learning', in Milestones towards lifelong learning systems, Elhers, S (Ed.), Danish University of Education Press, Denmark

- Pedersen, J J (2006) 'The economic imperative for Lifelong Learning in Europe: Challenges from Demographic trends 1995-2045' in Milestones towards lifelong learning systems, Elhers, S (Ed.), Danish University of Education Press, Denmark

- Richmond, M, Robinson, C and Sachs-Israel (2008) 'The Global Literacy Challenge', UNESCO, Education Sector, Division for the Coordination of United Nations Priorities in Education

- Rubenson, K (2006), 'Constructing the lifelong learning paradigm: Competing vision from the OECD and UNESCO', in Milestones towards lifelong learning systems, Elhers, S (Ed.), Danish University of Education Press, Denmark

- Tharakan, M P K and Navaneetham, K (1999) 'Population Projection and Policy Implications for Education: A Discussion with reference to Kerala', Working Paper No. 296, Centre for Development Studies, Thiruvananthapuram, Kerala, India.

- Tight, M (1998) 'Lifelong Learning: Opportunity or Compulsion? , British Journal of Educational Studies, Vol.46, No.3, September, pp. 251-263

- Williamson, A (1997) 'You are never too old to learn: Third-Age perspectives on lifelong learning', International Journal of Lifelong Education, Vol.16, No.3, May-June, pp.173-184

- Wilson, J D (2001) 'Lifelong learning in Japan- a lifeline for a 'maturing' society', International Journal of Lifelong Education, Vol.20, No.4, July-August, pp. 297-313

- World Bank (2003) 'Lifelong Learning in the Global Knowledge Economy: Challenges for Developing Countries', World Bank Publication, Washington, DC, May

- World Health Organization (WHO) (2002), Health and Ageing- A Discussion Paper.

- World Health Organization (2021) 'Ageing and Health', accessed online https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/ageing-and-health

- Wolf, L (2000) 'Lifelong Learning for the Third Age', meeting on "Inter-Regional Consultation on Aging of the Population", hosted by the Inter-American Development Bank, Washington DC; June 1 and 2