Subscribe now to get notified about IU Jharkhand journal updates!

Driving ESG Integration in Upstream and Downstream Value Chains: A Strategic Review for B2B Manufacturing

Abstract :

In recent years, industrial manufacturing sectors have come under scrutiny due to the uncontrolled use of resources, waste generation, and harmful emissions, prompting a global call for responsible practices. The urgency of mitigating environmental harm while sustaining growth has led to an increased focus on integrating sustainability into core business strategies. Leading manufacturers are now prioritizing sustainable innovation and seeking partnerships with businesses that demonstrate environmental and social responsibility. As a result, sustainable supply chain management (SSCM) has emerged as a key approach for enhancing sustainability outcomes across both upstream and downstream operations.This review explores the evolution of SSCM, with particular emphasis on the Environmental, Social, and Governance (ESG) framework in B2B manufacturing industries. Drawing from research spanning from 1994 to 2024, this study highlights the growing significance of ESG indicators and the need for greater transparency in supply chain practices. It also underscores the pivotal roles of policymakers, corporate leaders, and supply chain managers in advancing ESG-aligned goals. By reviewing recent scientific literature, this paper provides a comprehensive understanding of the current landscape of sustainable supply chain practices and offers a conceptual framework for improving ESG performance across both supply chain segments. Furthermore, the review presents case studies from the chemical manufacturing sector, illustrating successful efforts in reducing environmental impact and establishing performance metrics for sustainability.

These case studies serve as valuable references for organizations looking to adopt SSCM practices. In conclusion, the paper identifies research gaps and offers recommendations for future studies, while also highlighting practical strategies for managers to implement and monitor sustainable supply chain initiatives effectively.

Keywords :

Sustainable Supply Chain Management; Environmental, Social, and Governance (ESG); Sustainability in Manufacturing; B2B Manufacturing; Sustainable Innovation; Waste Reduction; Greenhouse Gas Emissions; Supply Chain Transparency; Policy Impact on Sustainability; Upstream and Downstream Supply Chains; Sustainability Performance Indicators; Circular Economy; Corporate Social Responsibility; Environmental Impact Reduction; Sustainable Business Practices; Supply Chain Resilience; Sustainability ReportingIntroduction

Organizations are being increasingly held accountable for the impact of their actions on the environment. This transformation is being brought about not only by the regulatory bodies but also due to more aware customers taking up environmentally conscious decisions to be associated with organizations and businesses that take up necessary steps that are more in line with the needs of the current society regarding the sustainability of the environment as a whole and not just focusing only on the profit margin.

Sustainability is becoming more of a catalyst for innovation and change, a competitive differentiator, and a source of new value creation. ESG, without question, now has become the framework to assess the sustainability and the ethical processes of any organization. Businesses performing well in ESG metrics and maintaining transparency garner high ESG ratings which directly result in better funding and finances, enhanced brand image and reputation. According to Lee et al. (2024), management of ESG goals plays a centric role in the corporate outlook of an organization.

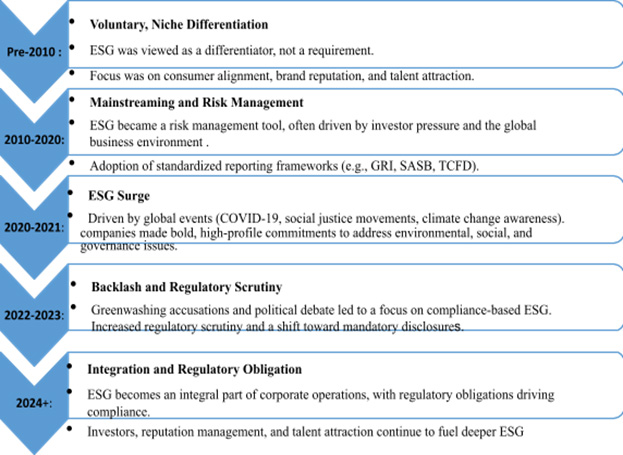

The evolution of ESG shows a remarkable shift from voluntary activities to mandatory compliance actions that have been shaped by both pressures from external agencies as well as internal corporate strategies. Although currently, the regulatory frameworks are setting the standards, businesses in the coming years will be more prone to look beyond the basic compliance standards as they aim to integrate ESG into their core business processes and other long-term goals. Soon, ESG will likely continue to expand its horizons, as a key driver of innovation, resilience, and sustainable growth in a fast-developing scenario while also being a tool for risk management for business entities. The ESG era moving from voluntary to mandatory requirements has been presented in Fig. 1.

Figure 1. ESG Era from Voluntary to Mandatory. (Source: Information from Websites)

Organizations are encouraged under the Triple Bottom Line concept (Cervellin et al., 2024) to think about how their operations effect people (e.g. customers, suppliers, employees, and society), the planet (environmental effects), and profit (economic viability). Businesses handle matters like worker happiness, safety, health, labor rights, and community involvement under the "People" dimension. Managing environmental effects, such as cutting carbon emissions, adopting sustainable production methods, and supporting clean energy regulations, are all part of the "Planet" component. The "Profit" component emphasizes the significance of long-term performance management by considering both monetary gains and intangible accomplishments like reputation, trust, and innovation.

As businesses and individuals, it is crucial that we understand and address the issue of climate change. The economic costs of climate change are astounding. As per the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), the global economy could lose a staggering $23 trillion by the year 2100 if we fail to recognize climate action in its true sense. From extreme weather events to rising sea levels, the financial toll is substantial. According to Deloitte CxO sustainability report (2024), reaching net-zero will transform nearly every aspect of the global economy, and the speed and scale of that transformation has accelerated in recent years even though it is less than what is needed to avert some of the worst impacts of climate change. Numerous businesses directly profit financially and commercially from their climate initiatives. Sustainability investments are increasing company growth and climate action going together.

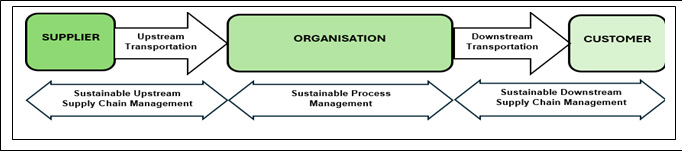

The implementation of sustainable supply chain management (SSCM) is a key to push businesses to focus on critical issues of the environment while providing benefits both in the economic and social sense. Supplier Sustainability is being recognized as one of the most significant contributors to the sustainability of a manufacturing organization (Gualandris et al., 2016) and so, most customers in the current global scenario are using the ESG lens to understand and make a proper analysis of the performance of their suppliers. According to Gualandris et al. (2016), sustainability performance, which is gauged by environmental and social (E and S) performance, can be improved by internal and external practices of an organization. Internal practices are reflected in the sustainable process management (SPM) of the manufacturing firm. External practices are completely impacted by the sustainability performance of the key suppliers of manufacturing firms. Sustainable procurement has the potential to ensure a significant reduction in the impact of the product bought on the environment.

According to Hassini et al. (2012), sustainable supply chain management (SSCM) is defined as the management of resources, processes, information, and finances to maximize the supply chain profitability, minimize the impact on the environment and maximize the social well-being. By the upstream supply chain, we can refer to the processes that relate to the procurement of the several raw materials for the B2B industries that are required to run the business under consideration, the production lines, while the downstream supply chain refers to those processes that are dealing with the disbursal of the finished goods, the distribution, the consumption of the goods and the disposal of the wastes.

Due to push from various stakeholders, especially customers, government regulatory bodies, community activists, non-governmental organizations (NGOs), and global competitors, many companies have adopted a certain level of commitment to sustainability practices. Other companies are still hesitant to commit sustainability measures, if they are not forced to do so by law. The commonality among these businesses is that they do not possess a common standard for the evaluation of the sustainability initiatives (e.g., Searcy et al., 2009; Tweed, 2010). Hassini et al. (2012) suggested the requirement of industry-specific research on sustainable supply chain management. According to Seuring et al. (2008), most of the research focused on green/environmental issues, social aspects and the integration of the three dimensions of sustainability (Economy, Environment and People) are inadequate.

The objective of current study is to review articles, sustainability reports from the corporate publications, thesis papers and review papers on sustainable supply chain management research during the last 30 years and analyze it from different perspectives, highlight the gaps in the literature that need further investigation. Another objective is to provide a conceptual framework for upstream and downstream sustainable supply chain management. Presented case studies on good practices of sustainable supply chain in a B2B manufacturing industry are references for organizations looking to adopt SSCM practices.

The manufacturing sector has been selected for this study because of the following reasons: Companies that follow lean manufacturing techniques are more likely to adopt sustainability practices (Hassini et al., 2012) and secondly, environmental regulations are more applicable for manufacturing plants (e.g. pollution control).

Literature Review:

Sustainability is considered as the license to do business in the twenty first century and a major component of this license is the supply chain management (SCM) (Carter et al., 2011). Govindan et al. (2014) opined that the primary goal of most of the innovations in supply chain management in the twentieth century was the reduction of waste for economic objectives, whereas in the twenty first century the term green, about the protection of the environment, has gained the center-stage. The sheer lack of relevant technology, according to the authors, is the most prominent barrier to the adoption of Green Supply Chain Management. So, collaborating with the customers may aid in the development of the technical expertise of the suppliers. Ahmed et al. (2022) suggests the usefulness of focus more in-line toward the achievement of the sustainability objectives of both the buyers and the suppliers. Businesses are now facing pressure from government regulatory bodies, competition from the global market, and the customers on several initiatives on the environment front (Diabat et al., 2014). Several large and ethical businesses are now including sustainability at the core of all their activities because of the regulatory requirements, push from the investors and expectations from the customers on the adherence of their business objectives towards sustainability criteria.

According to Gualandris et al. (2015), sustainability is progressing towards becoming a center point of concern for the manufacturing firms because of the strong impact that their operations are having on the social and environmental front. Such manufacturing firms are suggested to let themselves engage in sustainable supply chain management (SSCM) practices to achieve their goal to meet the economic, environmental and social criteria (Carter and Rogers, 2008).

According to Gualandris et al. (2016), SSCM has been developed within a firm, and it has evolved from being sustainable process management (SPM) to sustainable supply management (SSM). Sustainable process management indicates towards the practices taken sustainably, typically within the premises of the firm whereas, sustainable supply management involves collaboration with the supply chain for the sustainable enhanced performance of the individual businesses and the supply chain taken as a whole. Sustainable supply chain management (SSCM) is the key enabler that helps organizations to mitigate environmental issues, and provide economic and social benefits (Zailani et al., 2012). Although the internal practices involving Total Quality Management (TQM) aim to reduce the detrimental impact on the environment (Wiengarten et al., 2012), external practices are known to predict and resolve any environmental and social issues through collaboration with their suppliers, which directly result in the improved performance on sustainability for the organization (Gualandris et al., 2014). Kumar et al. (2012) opined that SSCM may ensure a reduction in the overall waste including energy, water, fuel consumption, and reduced packaging for the company. According to Gualandris et al. (2015), sustainable evaluation and verification (SEV) of supply chain include three interrelated dimensions viz. inclusivity, scope, and disclosure to identify key measures being taken, verify and analyze the data, verify materiality and resulting information.

Eccles et al. (2014) conducted a study over a period of 18 years to compare the performances of some High Sustainability firms with other Low Sustainability firms in the United States. According to their study, High Sustainability firms are those which implemented long back (by 1993) the policies directing their impact on the environment and the society including putting more enhanced emphasis on the selection of, monitoring, and evaluation of the performance of their suppliers based on the external environment and the social standards, while the Low Sustainability firms had not yet implemented these policies. The results of this study revealed that the long-term performance of High Sustainability companies is significantly higher in comparison to their counterparts, both in terms of the stock market as well as their growth financially. Vachon et al. (2008) suggests that the implications of the collaborative green supply chain practices (GSCP) can be the broadest with the suppliers. Collaborative GSCP has been known to forge several interactions between the organizations in the supply chain to set some common environmental goals, environmental planning in a joint fashion, and collaborative approaches to reduce the detrimental impact on the environment. It is considered that the upstream collaboration is known to be associated with the performance related to the production process, while the downstream collaboration has been known to be linked with the performance related to the product.

The findings of the study conducted by Hanninen, S. (2023) revealed that engaging in more sustainability-focused performance management of the suppliers is critical to meet the organization’s objectives regarding sustainability. The author has suggested that Environmental performance should be measured by the management of the emissions of Greenhouse gases, judicious usage of Resources, proper Waste Management taking sustainability into consideration, social performance to be measured by Workplace Safety, Health and Well-being, Human Rights and diversity, Community Engagement, and Governance performance to be measured by Fair business transactions, Information security, Business continuity management.

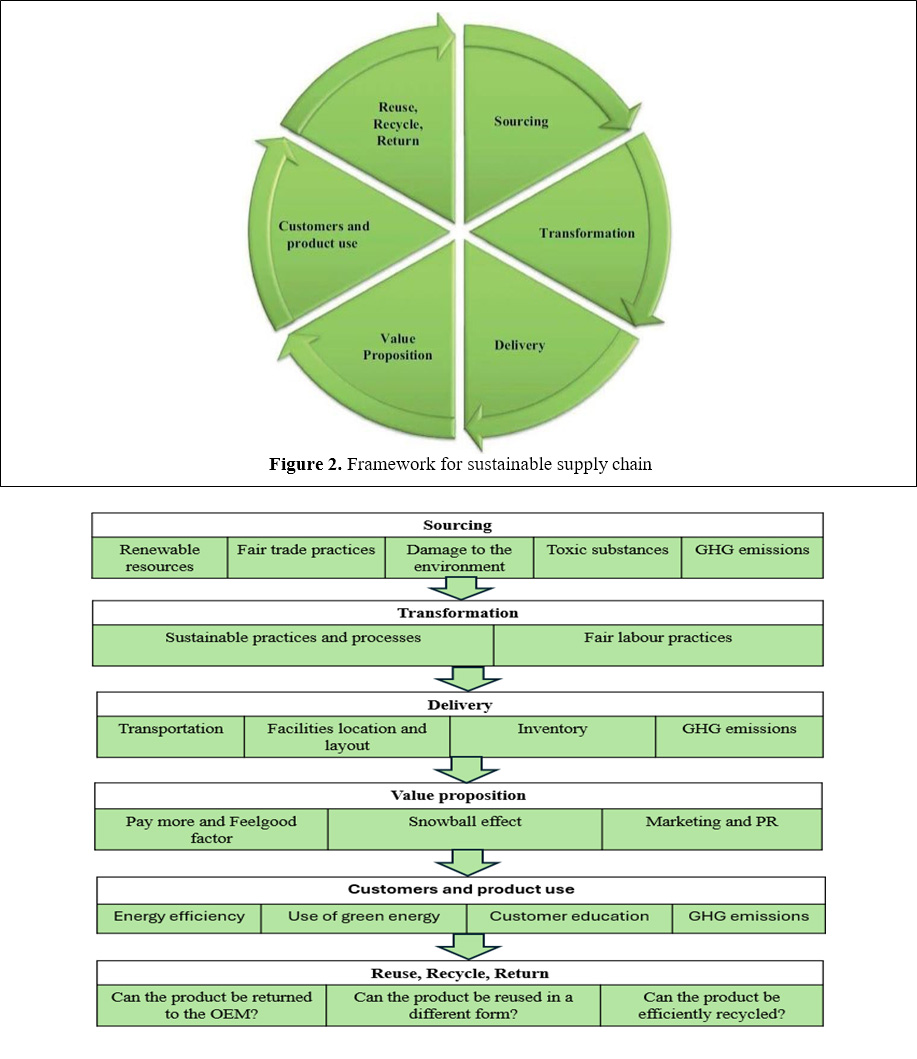

The results of the study conducted by Wong et al. (2012) suggest that manufacturing firms should prioritize the capability of environmental management of their suppliers in their green operations to be benefitted financially as well as environmentally. Sustainable production, as opined by Veleva et al. (2001), is the production of goods and services using processes and systems that can be considered as non-polluting, conserving of energy and natural resources, economically viable, safe and healthful for all the employees, communities, and customers engaging with the business, and rewarding for all working people both socially and creatively. The six major aspects of sustainable production are highlighted in the definition: use of energy and material (resources), economic performance, natural environment (sinks), workers, social justice and community development, and products. The authors emphasized some indicators that are applicable to the supply chain as the use of energy, use of hazardous materials, generation of waste, participation in Life Cycle Assessment (LCA) of raw material or packaging, safety training, adherence to EHS standards, adoption of ethics policy, reuse or recycle of product, product stewardship among others. Gualandris (2024) opined supply chains should positively contribute to and harmoniously integrate with the living systems around them. According to Winter et al. (2016), there is a need for the inclusion of environmental and social criteria for the selection of suppliers as well as for the evaluation of the suppliers in business with the organization already. These criteria include wastewater treatment and recycling, use of environmentally friendly raw material, management of hazardous substances, health and safety practices, strict prohibition of child labor as well as forced labor, no form of discrimination, freedom of association of all workers with the business, consideration of the working hours, proper employment compensation, etc. Hassini et al. (2012) proposed following framework for sustainable supply chain (Fig. 2) and some important issues for each function within the supply chain (Fig. 3).

Figure 3. Important issues for each function within the supply chain. [Source: Hassini, E., Surti, C., & Searcy, C. (2012). A literature review and a case study of sustainable supply chains with a focus on metrics. International journal of production economics, 140(1), 69-82]

Sustainable Supply Chain:

Systematic reviews on sustainable supply chain have been done from time to time. Some of these review articles covering a period of 1994 to 2024 were studied (except a few literatures published long ago) and the gist of points gained are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1: Summary of insights from the literature.

Sl. No |

Title of paper/ Article |

Source: Name of journal/ Magazine etc. |

Year of publication |

Author |

Review period |

Gist of points gained |

1 |

A framework of sustainable supply chain management: moving toward new theory |

Internationaljournal of physical distribution and logistics management |

2008 |

Carter, C., Rogers, D.S., |

2007 |

Reviewed 166 publications and interviewed 35 supply chain managers in 28 Fortune 1000 companies in the USA and Germany and a framework has been provided to develop SSCM practices in the organizations

SSCM framework may be used in the integrative, strategic fashion to identify the environmental and social initiatives that can have the maximum economic impact; for example, the points which can be examined across the primary activities of the value chain are activities in inbound and outbound logistics such as use of packaging and disposal, warehouse safety, and the impact of transportation such as emissions and safety; operations issues including technology development, emissions, energy use, hazardous materials, worker safety and human rights; purchasing from and developing minority-owned suppliers, ensuring safe and humane working conditions at suppliers’ plants, after-sales service concerns comprising reverse logistics issues including environmentally sound disposal and disposition Scales to be developed to measure the triple bottom line, the supporting facets of SSCM, and the relationships among resource dependence, external uncertainty, vertical coordination, imitability, and supply chain resiliency need to be analysed |

2 |

Green supply-chain management: a state-of-the- art literature review. |

International Journal of Management Reviews |

2007 |

Srivastava, S.K. |

1994 to |

While reviewing 227 books and articles, it is found there is an opportunity to implement integrated business strategy comprising of product and process design, manufacturing, marketing, reverse logistics and regulatory compliance in the context of Green Supply-Chain Management (GrSCM) and it needs further research within a supply chain Requirement of further research on how companies should store, process, and dispose of returned goods and how to sell unwanted products have been suggested. |

Sl. No |

Title of paper/ Article |

Source: Name of journal/ Magazine |

Year of publication |

Author |

Review period |

Gist of points gained |

3 |

From a literature review to a conceptual framework for sustainable supply chain management |

Journal of cleaner production |

2008 |

Seuring, S., |

1994 to 2007 |

On review of 191 journal articles, a conceptual framework was developed to summarize the research on SSCM comprising three parts; Most of the research is focussed on green/environmental issues, social aspects and the integration of the three dimensions of sustainability (Economy, Environment and People) are inadequate |

4 |

A literature review and a case study of sustainable supply chains with a focus on metrics |

Internationaljournal of production economics |

2012 |

Hassini, E., Surti, C., & |

2000– 2010. |

On review of 707 papers, it was observed that Majority of the papers focused on manufacturing sectors A sustainable supply chain was shown as wheels constituting of six spokes, representing the major relevant functions within the chain: sourcing, transformation, delivery, value proposition, customers, and recycling; major issues of each of these functions were illustrated Significant number of Sustainable performance indicators used in the literature have been highlighted; however, industry-specific research on sustainable supply chain management has been suggested Pricing to be considered as an important parameter of the value proposition to the customer Inventory management should be considered within a sustainable supply chain. Large firms have an advantage for adopting sustainable practices more than SMEs and that SMEs adoption is necessary in the long run The most reported supply chain indicators are ‘‘policy, practices, and proportion of spending on locally based suppliers’’ |

Sl. No |

Title of paper/ Article |

Source: Name of journal/ Magazine etc. |

Year of publication |

Author |

Review period |

Gist of points gained |

5 |

A systematic review of sustainable supply chain management in global supply chains |

Journal of cleaner production |

2019 |

Koberg, E., & |

2003 to 2018 |

Reviewed 66 articles which are relevant to global SSCM |

6 |

Environmenta l, social and governance issues in supply chains. A systematic review for strategic performance |

Journal of Cleaner Production |

2024 |

Truant, E., Borlatto, E., Crocco, E., & Sahore, N. |

2000 to 2022 |

Reviewed 36 articles which are relevant to SSCM and following emerging themes in supply chain and ESG literature were identified:

ii.The role of policymakers and institutions literature stream has developed and evolved over time |

Source: Literatures as mentioned in the table

Upstream Supply Chain and Sustainability:

Green Procurement and Ethical Sourcing:

According to various literatures (Fahmi et al.,2023, Sadiku et al., 2021) green procurement is the term used to describe purchasing practices for businesses that prioritize minimizing their environmental effect taken up in the process. Green procurement practices enable industries to care for the environmental impact by looking after the reduction of greenhouse gas emissions, and release of contaminants into the air, enhancement of the energy and water efficiencies in the business process, reduction of the release and usage of Ozone depleting substances, reduction of waste generation and focusing on the reuse of substances as much as possible, reduction of the hazardous wastes, reduction and lessen the use of solid waste, supporting a much healthier working environment for the employees in the organization. Some prime examples of green procurement include, purchasing of recycled stationery and other equipment in the office can ensure that recycling is being taken up in the office premises, collecting and treatment of the household wastes to be used again for productive activities, switching to energy efficient office practices and equipment to ensure low energy usage and reduction in the bottom line to ensure proper take care of the environmental impact.

Ethical sourcing refers to a business practice that ensures products and services are obtained in a way that is fair to workers (upholding labor rights), the environment and transparent about supply chain practices.

Supplier Engagement and Collaboration:

Mahler (2007) mentioned that taking improvement actions on sustainability by the companies allows them to cut costs, innovate new products, avoid long-term issues to get an edge over other companies and the companies are expected to participate with suppliers in joint programs on sustainability and to track sustainability metrics.

According to Grimm, J. (2021), companies are being known to use practices for engaging their suppliers to make them conform to the sustainable practices that are being used these days. This approach has been found to be more risk driven as well as more transactional. It is also known as a coordinated approach. Another method is also available, often known as the collaborative approach. It is often used to elicit commitment from the suppliers on the matter sustainability and promote innovations in their own respective fields, with the help of methods of customizations and partnerships. Collaborative practices often have proven to be investment based. It prioritizes decentralized and shared decision-making and is often found to be bi- directional. Any changes that are then recommended are then implemented after proper mutual understanding and discussion.

The analysis of Stan et al. (2023) suggests that ESG factors can have a significant impact on the supply-chain performance like perfect order rate, costs, order execution rate and cash-to-cash cycle time. Saurage (2017) recommended that CSR investment of supplier is translated into reputation in the market and competitive advantage with B2B Customer. Lambert (2017) suggested that an organization can be successful if their management can foster cross-functional and cross-firm processes

As per the study conducted by Villena et al. (2020), the suppliers who are low in the supply chain generally do not comply with the standards and companies should include lower-tier suppliers in the overall sustainability strategy. As recommended by Christmann (2000), firms should select the best practices on environment based on their existing resources and capabilities. Chvátalová et al. (2013) mentioned economic performance of corporate can be evaluated through the effects of ESG indicators. As per De Mendonca et al. (2019), environmental performance of companies can have positive effect on their financial performance provided there is market support for improved environmental performance.

As per the report shared by PwC (2024) from the 6th ICC Sustainability Conclave over the public domain, it is quite evident that the market leaders are also leading the way for newcomers to follow in their footsteps in achieving the goal of sustainability in their supply chains. For instance, Tata Chemicals has already embarked upon the journey to build an integrated framework of policies, practices and several assessments that have their primary focus on the ESG aspects of supply chain. Pidilite Industries focusses on regular audits and regular collaboration with its suppliers

Risk Management in Upstream Sustainability:

Sustainable sourcing needs focus on the management of risks that are combined with the environmental resource depletion, scarcity of resources, and the associated unrest in the social context. Colicchia and Strozzi (2012) have conducted a comprehensive literature review on the risk management needs in the supply chain. They have stressed the importance of risk management effectiveness to ensure the resilience that is prevalent and the competitiveness of the supply chains. Uncertain business environments also make it difficult for implementation of the sustainable practices that are planned for the supply chains.

Downstream Supply Chain and Sustainability:

Green Logistics and Sustainable Distribution:

According to Grzybowska (2012) special attention should be given to the transport sector and measures to reduce CO2 emissions. As mentioned by Arroyo et al. (2023), Green logistics is concerned with sustainable production and distribution of goods by taking environmental and social factors into account. Green logistics refers to the methodologies that are undertaken to reduce the impact of transportation and the distribution of goods on the environment. It also simultaneously considers the reduction of emissions, optimization of the routes that are being taken for transportation, and minimization of the waste that is generated in the packaging process. New-age processes have seen the usage of EVs (electric vehicles) to reduce emissions, optimize warehouse energy consumption, and the use of bio-degradable packaging methods. Sustainable distribution methods have been found to reduce the carbon footprints and the cost efficiencies, because the optimization of the logistics has been found to reduce emissions as well as take care of reduction of transportation and the operational costs.

Circular Economy in the Downstream Supply Chain:

The concept of circular economy is gaining momentum. The circular economy, which aims to move economic and production processes away from linear take-make-dispose to more circular and regenerative processes, can significantly contribute to sustainable development and reduce the pressure on finite resources. As mentioned by Geissdoerfer et al. (2017), Circular Economy is ‘an industrial economy that is restorative or regenerative by intention and design’. Omar (2020) conducted an extensive study on the effects of the circular economy practices on the performance of the supply chain in view of the chemical and the allied firms in the region of Kenya and observed that methods of circular supplies, product extensions, recovery of the resources, and development of products have been used by these allied industries. They also equally used the waste reduction methods throughout the supply chain, taking measures to reduce emissions. The study finally concluded that 88.2% of the performance of the supply chain was affected by the above-mentioned methods of circular supplies, product extensions and others. The driving force behind circular material flows is the reverse logistics, as they promote the return of products to the supply chain for value extraction (Prajapati et al., 2019).

Customer Behavior and Sustainability:

Kochina (2019), during her studies regarding the role of customer behavior in shaping the downstream supply chain sustainability remarked that customers are well versed regarding the sustainable practices and there has been an upwards trend of customers being increasingly aware regarding these aspects of the businesses with which they are dealing with. In the last few years, it has so become that sustainability reports of the B2B industries are being heavily sought after and scrutinized. This is also helping the customers make well-informed decisions and aiding the industries to make a reputation among their customer base for being a more sustainable organization than their peers in the same industry.

As per the study of Hegab et al. (2023), a company’s sustainability objectives can be fulfilled more if the suppliers themselves follow sustainability-related practices. As per the author, environment related performances need to be measured by greenhouse gas emissions (GHGs), use of resources, management of the wastes, workplace safety to be monitored to calculate the social performance along with health and well-being of the manpower engaged in the business, engagement with the community, and for the measurement of the performance of the governance, fair business transactions along with information security and management of the business continuity need to be considered. According to Weiß et al. (2017), sustainable supply chain management is not only for the direct suppliers, but sub-suppliers also to be included.

As recommended in Deloitte CxO sustainability report (2024), for the benefit of both businesses and the planet, organizations should a) build on their key strengths in driving the new products and services needed in the low-emissions economy, embedding sustainability in key processes, and leveraging their influence with suppliers and policymakers b) Consider the full array of pathways to creating impact by extending the reach of their sustainability efforts to customers, employees, suppliers, policymakers, non-governmental organizations, and community members c) Collaborate with a wide range of stakeholders and even competitors to get amplified sustainability impacts; Collaboration across the supply chain to get industry-wide improvements and foster innovation, working with suppliers to help meet sustainability criteria can enhance the overall environmental performance of products. Partnering with regulators can help shape supportive policies, while collaborations with competitors can drive standard- setting and leading practices in sustainability d) Explore the full range of benefits to make the business case by moving proactively to put sustainability at the heart of their business with the evolution of market and regulatory demands so that they are well-positioned to thrive in the economy of the future.

Pagell (2014) suggested environmental impact of supply chain can be best measured based on the life cycle assessment (LCA) of the product or service provided by the chain. According to Dufvelin (2018) mentioned that the indicators for Sustainable operations and responsible conduct are related to employees (e.g. employee satisfaction, occupational health and safety), community (e.g. Make people move -initiative like sports etc.), human rights (e.g. supplier social audits), emissions (e.g. CO2 emissions) , environmentally friendly products ( e.g. Product testing), chemicals, business ethics (e.g. Code of conduct), customers (e.g. customer satisfaction) and suppliers (e.g. supplier code of conduct). Bagheri et al. (2007) suggested process indicators can be used to measure sustainable development.

Methodology:

The focus of this study has been on the B2B manufacturing industries and how they are striving to be increasingly sustainable by inculcating sustainable business practices in their manufacturing operations as well as sourcing their raw materials from sustainably sourced units through a sustainable supply chain. Data sources that have been referred to include academic literature, sustainability reports from the corporate and scientific publications. Sustainability in supply chains is more prominent in the B2B businesses which combine the manufacturing setups, retail and the technological aspects that are associated with the business.

Case studies described in this paper were compiled by gathering information on the initiatives taken on sustainability as published in sustainability reports (Annual Integrated Reports - PCBL Chemical Limited) of chemical product manufacturing companies and by interacting with related industrial experts. In this review, only works from journals and sources primarily focused on social and applied sciences were considered, and those that did not discuss universally applicable or replicable "sustainable" practices were excluded from the review. This paper aims to analyze and synthesize pertinent literature from journals that can assist both academics and practitioners in developing customized strategies to address their specific business needs. Consequently, the paper emphasizes the tactical and operational dimensions of sustainable supply chains.

Major points gained from scientific papers on this topic are briefly presented, which serve as a scientific foundation and led us to undertake our study to contribute to the body of scientific knowledge on this little-addressed topic.

Findings and Discussion:

Integration of Sustainability in Upstream Supply Chains:

Responsible and ethical sourcing, evaluation and development of suppliers have now become the industrial norms. By integrating sustainability into upstream supply chains, companies can mitigate the impact on environment by adopting the best practices to minimize emissions, reduce waste, and promote the use of renewable resources. By integrating fossil-based, recycled/reused, bio-based, and CO2-X based materials, the industry can enhance supply chain resilience and economic stability. To develop sustainable raw materials, manufacturers can engage with their upstream value chain partners for Life Cycle Assessment (LCA) during product development.

Green Logistics and Reverse Logistics in the Downstream Supply Chain:

Considering the current needs and challenges faced by the supply chains of the B2B manufacturing industries, green logistics and reverse logistics seem to be the logical explanation to achieve our goal of a sustainable supply chain and sustainable development goals (SDGs). According to Arroyo et al. (2023), the implementation of reverse and green logistics will result in sustainable practices being followed but the implementation itself has often faced challenges, for instance: lack of conviction from the top management, lack of a proper plan, a team in place to oversee the proper implementation, and a strategy for the marketing. Such hindrances are proving to be quite a whole bunch of roadblocks in the implementation of green logistics and reverse logistics approaches.

Implementing a reverse logistics plan is a double-edged sword. It can reduce costs and lead to savings by the reduction of the need for newer raw materials for the process, it reduces the amount of waste generated, as well as reduces the impact on the environment but it is a costly affair and takes a toll on logistics also. It needs significant investments and needs enhanced customer engagement.

Customer Behavior and Its Influence on Supply Chain Sustainability:

Customer behavior has come among the top few decision-makers when talking about the downstream supply chain management. The sky rocketing demand for sustainably sourced, manufactured and delivered products has made businesses reconsider their stand on sustainability and enforce measures among their ranks and processes that take sustainability into account. Customers are non-negotiables expecting transparency from the businesses through which clear and detailed information can be made available to the public regarding the sustainability of the products being delivered, which has again led to product certifications. It has proven to be a win-win situation for both the customer and the business because now there has been a balance of trust between the two partners in the business.

Technological Innovations in Sustainability:

Just like other industries, environmental sustainability is also high on the agenda of the manufacturing industry. A key aspect of sustainability is decarbonization which can be achieved through transition to renewable energy sources (e.g. utilizing green hydrogen), adopting bio-based or low-carbon feedstocks, enhancing energy efficiency through advanced technologies (e.g. electrifying high-temperature processes), and utilization of Carbon-Capture- Utilization-Storage (CCUS). Technology has been naturally employed to aid humans in the process to implement technical aspects in the manufacturing industry especially to make the process more environmentally sustainable. AI and block chain technology are among the many technological methods being used to increase outreach, depth, traceability, and to trace that the products are being sourced ethically and in a sustainable manner. As a matter of which, AI and machine learning in supply chain management has also ensured more efficiency in resource allocation, reduction in waste generation, and it has also helped in better decision making for the matters of procurement, production planning as well as logistics.

Best Practices in Sustainable Supply Chain Management:

The best practices observed in the supply chain of B2B manufacturing sector are explained in the following sub-sections.

Collaboration with Supply Chain Partners:

According to Shivani (2023), industries face some major challenges in the implementation of sustainable practices in their supply chain. Some clearly visible challenges include the lack of visibility, lack of ideas for implementation of ESG in their supply chain, failure to identify opportunities for the implementation of ESG as well as no tracking method to clearly identify the progress of the implementation and benefits accumulated since the implementation of ESG into their supply chain domain.

Industries must collaborate directly in close connection with their supply chain partners to ensure greener operations in their upstream and downstream supply chain operations. It also includes focusing on clear goals in matters of sustainability, identifying and addressing the training needs for the suppliers and other stakeholders that may come up in the supply chain, offering incentives to their stakeholders for following sustainable practices in the business environment.

Technology and Innovation:

Ali and Gölgeci (2019) have seen through the path of supply chain research especially that is marked with the resilience with the conduction of the co-occurrence analysis parts. This helped in the development of the future research directions of the supply chain resilience which included resilience assessment, strategies related to resilience, and the role played by technology to enhance the supply chain resilience.

Technology can be taken up with more fervor to ensure that industries are having more depth and insight into their supply chain is to ensure that they are following sustainable methods. This can be done with the aid of block chains, AI and more innovations in the technological sector.

Customer Engagement and Transparency:

B2B manufacturing industries form the backbone of an entire group of industries as well as the nation. With the current wave of sustainable practices being inculcated into the supply chain processes, it can be extremely essential that the customers of the industries are kept properly informed about the sustainability of the products that they are purchasing. Customers are the true evaluators of a business and hence their trust is paramount to the success of the business. By making the transparency of the sourcing, manufacturing as well as the logistics end, B2B industries can build unprecedented trust among their customers which will invariably increase their customer loyalty and hence would ensure sustainable growth of their business. The right tools and certifications from the right certifying bodies form the right steppingstone to achieve the goal of building up customer trust.

For instance, from the sustainability report of Cabot Corporation available in public domain, we know that, quite clearly as a B2B manufacturing industry, the organization has taken measures to ensure sustainable practices within the organization as well as it has noted to keep its customers up to date with the happenings within its organization as summarized in Table 2.

Table 2. Sustainability data performance summary.

Case studies:

This section presents case studies from the chemical manufacturing sector that highlight successful initiatives in reducing environmental impact while establishing measurable sustainability performance metrics. The case company under study is a leading carbon black manufacturer in India, operating five strategically located production facilities across the country. The primary raw material, Carbon Black Feed Stock (CBFS), is largely sourced from Fluidized Catalytic Cracker (FCC) bottom products of refineries. A significant share is imported from the US Gulf Coast, while the remainder is procured from domestic suppliers. Alongside CBFS, other process chemicals and binders are sourced locally. Within refractory-lined reactors, the process generates carbon black along with gases such as CO₂, CO, CH₄, C₂H₂, H₂, and N₂. The finished carbon black is packed either in 25 kg paper bags or in polypropylene (PP) bulk bags ranging from 500–1300 kg, catering to both domestic and international markets.

Reuse of Plastic Pallets:

Traditionally, new plastic pallets (~8 kg each) were used for transporting bulk bags to customers, while new wooden pallets were employed for internal storage. This practice significantly increased plastic consumption and waste generation. To address the associated environmental challenges and reduce GHG emissions, the company collaborated with one of the customers to establish a return-and-reuse program for plastic pallets. In FY 2023–24, 11,400 pallets were returned, with 90% reused for fresh dispatches and 10% repurposed internally, replacing wooden pallets. This initiative reduced plastic consumption by 91.2 MT, avoided 314 tCO₂e emissions, and replaced 1,140 wooden pallets—conserving approximately 2.5 tons of carbon sequestration. Additionally, it generated annual cost savings of ~₹1 crore through reduced procurement. The initiative offers significant scalability potential if extended to additional customers.

Optimization of Transportation Distance:

Initially, delivery distances were high, contributing substantially to Scope 3 emissions. Despite having multiple strategically located plants, dispatches were not fully optimized. By aligning shipments with the nearest plant based on customer-specific requirements, the company reduced delivery distances from 72.5 km/MT in FY 2023–24 to 66.6 km/MT in FY 2024–25, an 8.1% reduction. This optimization avoided 1,626 tCO₂e emissions and saved ₹62.7 lakhs in transportation costs.

Modal Shift from Road to Coastal Shipping:

Previously, all domestic deliveries relied exclusively on road transport, leading to elevated emissions. To improve logistics sustainability, the company adopted coastal shipping for select deliveries. This modal shift resulted in a reduction of 315 tCO₂e emissions for 3,527 MT of product transported to the same group of customers and established a more sustainable model for recurring deliveries. Further expansion of this practice can enhance environmental and economic benefits.

Recycling of Community Wastewater:

At one facility, untreated community wastewater was previously discharged without reuse. The company initiated a program to test, divert, and treat this wastewater for reuse in production. Approximately 500 kL/day (182,500 kL/year) was recycled, reducing dependency on raw water resources. This initiative not only mitigated pressure on freshwater supplies but also generated annual savings of ₹45.62 lakhs. The program can be scaled by upgrading pump and filtration capacity and replicated at other sites.

Enhancing Bulk Bag Loadability:

Lower product density restricted bulk bag utilization, resulting in increased plastic consumption and transport emissions. By optimizing process parameters, the company increased product density for two major grades, enabling ~5% higher packing weight per bag. For 45,452 MT of material, this saved 1,694 bulk bags, reduced plastic usage by 7.6 MT, eliminated 141 truck trips, and cut travel distance by 123,955 km. Overall, this improvement avoided 118 tCO₂e emissions and reduced transportation costs by ₹4.54 lakhs. The approach can be replicated across additional product grades.

Bulk Bag Take-Back Program:New PP bulk bags were historically used only once, contributing to plastic waste. A customer partnership enabled a return-and-reuse program, achieving reuse of 183 bags per month (~10 MT plastic saved annually). This reduced packaging costs by ₹20 lakhs/year, with strong potential for wider adoption across the customer base.

Reusing Bale Covers as Container Liners:

For containerized deliveries, new plastic sheets were used to line container floors, which were subsequently discarded as waste. Meanwhile, discarded PP bale covers from bulk bag packaging offered untapped reuse potential. By stitching bale covers into liners, the company avoided 3.72 MT of plastic consumption across 1,958 containers in FY 2022–23, saving ₹4.76 lakhs. Wider deployment across all shipments can further magnify these benefits.

Optimization of Air Header Lines:

At one plant, separate high- and low-pressure air headers operated inefficiently. Multiple high-pressure blowers often delivered excess air during low-demand grades, leading to energy waste. By interconnecting the two systems using scrap pipes and a pressure-reducing valve, the excess air was efficiently redistributed, and blower RPMs were optimized. Through this initiative, there were annual power savings of 2591.5 MWh and cost savings ~₹1.5 crore and GHG emission reduction by 1884 tCO2e.

Collectively, these case studies demonstrate the effectiveness of Sustainable Supply Chain Management (SSCM) practices in the chemical manufacturing sector. The initiatives significantly reduced environmental impacts particularly plastic waste, freshwater use, transportation-related emissions, and energy consumption while also generating substantial cost savings. Importantly, each case illustrates scalability and replicability, offering practical models for other organizations seeking to integrate sustainability with operational efficiency and profitability.

Future Research Directions:

Future research scope can delve into more details that can ensure more environmentally sustainable methodologies being taken up in the upstream and downstream processes of the supply chain, more awareness regarding the governance point of view, carbon-capture-utilization and storage (CCUS), carbon pricing, the proper use and effectiveness and efficiency of the circular economy practices that focus on the B2B industries. More focus can be taken up on the use of Artificial Intelligence and block chain to track the effectiveness of the use of ESG methodologies and tracking the growth of the upstream and downstream processes in the supply chain.

Conclusion:

The study offers critical insights into sustainable supply chain management, highlighting both its practical relevance and academic contributions. The key findings, theoretical implications, and actionable recommendations are synthesized in the following sub-sections.

Summary of Key Insights:

ESG in both arms of the supply chain, namely the upstream and the downstream, has been seen to offer well-known benefits that have been known to inculcate massive savings in the costs incurred by the B2B industries, mitigate the business risks associated with them, and give a huge uplift to their brand image and reputation in the public forum. The combination of green procurement as discussed, sourcing of sustainable goods in a sustainable manner and following labor practices that can be considered ethical, taken up with green logistics and circular economy models by the B2B industries is part and parcel in the journey to achieve and maintain a supply chain that can be considered as truly sustainable. The role of ESG in identifying the major issues and opportunities in the supply chain of the B2B industries has been realized and key insights generated for implementation. The case studies described in this paper show how an organization can get significant benefits impacting planet and profit by taking simple steps which can serve as valuable inputs for organizations looking to adopt SSCM practices.

Academic Implications of the Study:

This paper provides a comprehensive review of the literatures on sustainability, introduces sustainability to the field of supply chain management, and expands the conceptualization of sustainability beyond the triple bottom line to consider key supporting parts which are put forward as requisites to implement SSCM practices. The conceptual framework of sustainable supply chain management as depicted in this paper, along with the Key Performance Indicators (KPI) related to ESG issues in supply chain segregated into the leading indicators and lagging indicators contribute to the existing body of knowledge.

Recommendations for Advancing Sustainable Supply Chain Management:

To strengthen Sustainable Supply Chain Management (SSCM), organizations must adopt a holistic approach that combines collaboration, innovation, and transparency. The following recommendations are proposed based on both theoretical insights and practical evidence from industry applications.

Collaboration with Supply Chain Partners:

B2B manufacturing industries should prioritize deeper engagement with supply chain partners to establish and enforce sustainability standards. Collaboration can take both collaborative forms—fostering mutual trust, shared objectives, and joint problem-solving—or authoritative forms, where influence is exerted through power asymmetries and compliance requirements. Regardless of approach, meaningful progress requires modifying suppliers’ behavior (e.g., attitudes, awareness, and willingness to adopt sustainability practices) and transforming suppliers’ operations (e.g., upgrading processes, adopting new technologies, and improving resource efficiency).

Adoption of Advanced Technologies:

Investment in emerging technologies is essential to meet the growing sustainability expectations of global markets. Digital tools such as blockchain, IoT, and AI can enhance traceability, improve efficiency, and reduce environmental impact across the supply chain. In addition, green technologies—including renewable energy, advanced water treatment, and sustainable packaging—provide tangible pathways to reduce emissions and resource consumption.

ESG Transparency and Reporting:

Organizations must enhance transparency regarding their Environmental, Social, and Governance (ESG) performance. Transparent reporting ensures accountability, strengthens stakeholder trust, and extends the reach of sustainability initiatives throughout the supply chain. Establishing robust disclosure mechanisms also facilitates benchmarking against global standards and enhances investor and consumer confidence.

Corporate Interventions for Emission Reduction:

Corporate initiatives to reduce above Scope three emissions should adopt a dual strategy:

- Behavioural Interventions: shaping supplier values, beliefs, and willingness through awareness programs, training, and incentives.

- Operational Interventions: driving systemic change through improved product design, process optimization, and technology adoption.

Customer Engagement and Education:

Sustainable consumption patterns cannot be achieved without active participation from end-users. Organizations should invest in customer education and engagement strategies that highlight the benefits of sustainable products and encourage responsible usage, disposal, and recycling. This long-term cultural shift will reinforce demand for sustainable practices across the supply chain.

Continuous Monitoring and Improvement:

Sustainability is an evolving agenda that demands continuous improvement. Organizations must spotlight best practices, monitor ESG performance rigorously, and enhance metrics in response to changing regulatory, market, and environmental contexts.

Strengthening Supplier Selection and Evaluation:

Sustainable supplier selection forms the foundation of SSCM. As emphasized by Li et al. (2019), it is critical to establish structured frameworks for defining sustainable supply chain practices and evaluating supplier performance. Clear and measurable performance indicators should be prioritized, with provisions for refinement to ensure better alignment with sustainability goals (Schumann, 2010).

Role of Non-Traditional Actors and Governance Mechanisms:

Non-traditional actors play pivotal roles instigating, supporting, facilitating, and leading sustainability initiatives. Building governance mechanisms around these roles (e.g., campaigning, providing training, developing standards, and connecting actors) can accelerate the diffusion of sustainable practices throughout the supply chain (Carmagnac, 2021).

Development of ESG Key Performance Indicators (KPIs):

ESG-related KPIs in supply chains should be classified into:

- Leading Indicators: forward-looking metrics that anticipate risks and opportunities (e.g., supplier audits, investment in renewable energy, adoption of circular economy practices).

- Lagging Indicators: outcome-based measures that reflect past performance (e.g., actual reductions in emissions, waste, or resource use). As summarized in Table 3, this dual approach enables organizations to balance proactive measures with outcome verification, thereby creating a robust performance monitoring framework.

Table 3. ESG KPI for B2B manufacturing industries

KPI ON ENVIRONMENT |

|

Leading Indicators (Proactive) |

Lagging Indicators (Reactive) |

GREEN HOUSE GAS EMISSION AND CLIMATE IMPACT |

|

Percentage reduction in carbon emission intensity |

Total greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions under |

(emission per unit of production or revenue in tCO2e/MT |

Scope 1, 2, and 3 (tCO2e) |

or tCO2e / INR) with respect to the baseline and alignment |

|

with published SBTi target |

|

Reduction in VOC (Volatile Organic Compound) per year (Ton / Year) |

Number of environmental incidents or spills (No / Year) |

Number of projects on Carbon Capture, Utilization and Storage (CCUS) implemented |

Other emissions (SOx, NOX, PM) (Ton/ Year) |

Development of GHG emission reduction performance- linked executive compensation plans |

Percentage of products covered under LCA to monitor environmental impact of products and |

ENERGY USE AND EFFICIENCY |

|

Percentage increase of renewable energy used in operations and alignment with the published target (%) |

Total energy consumed (MWh/year) |

Reduction in energy intensity (kWh/unit of production) year-on-year and alignment with the published target (%) |

Energy consumption per unit of output (kWh/unit) |

Successful implementation rate of energy efficiency projects |

|

WATER MANAGEMENT |

|

Reduction in water consumption intensity (kL /unit of |

Total water withdrawal and consumption (Liters |

production) year-on- year and alignment with the |

/year) |

published target (%) |

|

|

Percentage of water recycled or reused |

|

Zero Liquid Discharge compliance |

WASTE REDUCTION AND RECYCLING |

|

Percentage waste diverted from landfill and alignment with the published target (%) |

Total waste generation (tons/year) |

Reduction in hazardous waste generation (tons/year) and alignment with the published target (%) |

Quantity of hazardous waste safely disposed or treated (tons/year) |

Percentage of operations using circular economy practices |

Compliance with Extended Producer Responsibility (EPR) |

Increase in sustainable (recycled or renewable) material usage (circular economy practices) in production (%) |

|

LAND USE AND BIODIVERSITY |

|

Number of biodiversity conservation projects launched |

Total area of land or habitat restored (hectares/year) |

Number of saplings planted and meeting the target |

|

Percentage of sites with biodiversity mitigation plans |

|

Net reduction in deforestation from operations |

|

COMPLIANCE WITH ENVIRONMENTAL STANDARD AND REGULATIONS |

|

Frequency of the training programs conducted related to environment |

Certification on environmental management system |

Number of environmental audits conducted to track the efforts regarding compliance and identify the associated |

Reports of non-compliance with environmental standards |

Environment policy introduced and implemented |

Fines or penalties for non-compliance with environmental laws |

KPI ON SOCIAL |

|

Leading Indicators (Proactive) |

Lagging Indicators (Reactive) |

EMPLOYEE SATISFACTION AND RETENTION |

|

Employee training and development hours per employee in a year |

Employee turnover rate (%) |

Frequency of employee engagement surveys conducted |

Results of employee engagement surveys (average score) |

Number of leadership development programs initiated to build a leadership pipeline |

Employee Net Promoter Score (eNPS) |

Recognition programs for employee achievements |

|

DIVERSITY EQUITY AND INCLUSION (DEI) |

|

Representation of various demographics (e.g. Gender, Ethnicity) in the workforce |

Percentage of women in leadership role |

Diversity in hiring practices (% of underrepresented groups hired) |

Pay ratio comparison across demographic groups |

ENGAGEMENT OF STAKEHOLDERS |

|

Community investment as a percentage of revenue |

Social impact metrics of community investments (e.g., number of beneficiaries) |

Number of consultations or community meetings held annually |

Percentage of new hires sourced locally |

Volunteer hours contributed by employees to community programs (CSR) |

Customer satisfaction score |

Stakeholder engagement initiatives held annually |

Recognition or awards received for social responsibility initiatives |

Partnerships with educational institutions for internships/apprenticeships to demonstrate the organization's contribution to skill development and |

Number of initiatives supporting small and local businesses to enhance local economic development |

HEALTH AND SAFETY |

|

Percentage of employees covered by occupational health and safety programs |

Number of workplace accidents or injuries reported in a year |

Frequency of health and safety training sessions held |

Lost Time Injury Frequency Rate (LTIFR) |

Conducting health and safety assessment (like HIRA assessment) at the facility |

Certification on Occupational Health and Safety Management System (e.g. ISO45001) |

EMPLOYEE WELLBEING |

|

Percentage of employees engaged in wellness programs that promote health and well-being. |

|

Availability of employee assistance program to support mental health |

|

Improvement in employee satisfaction survey results |

|

Initiatives promoting work-life balance (e.g., flexible work policies) |

|

LABOR AND HUMAN RIGHTS |

|

Percentage of sites covered in audits conducted to assess the compliance with Human Rights and implementation of policies to prevent forced labour, child labour, human trafficking, discrimination, or harassment based on race, sex, colour, national or social origin, ethnicity, religion, age, disability, sexual orientation, gender identification or expression, political opinion or any other status |

Number of reported cases of discrimination or harassment |

Policy implemented to ensure minimum wage, weekly off |

Number of reported cases of deviation from labour laws (to prevent forced labour, child labour, human |

KPI ON GOVERNANCE |

|

Leading Indicators (Proactive) |

Lagging Indicators (Reactive) |

BOARD OVERSIGHT AND STRUCTURE |

|

Percentage of independent directors on the board |

Turnover rate of board members or executives (%) |

Diversity on the board of directors (% representation of women, underrepresented group, experience, industrial background etc) to indicate inclusivity in leadership roles. |

Percentage of board members receiving |

Existence of board level ESG committee |

|

Frequency of board meetings conducted |

|

EXECUTIVE ACCOUNTABILITY |

|

Percentage of executive pay tied to ESG compensation |

CEO compensation as a multiple of median employee earnings |

CODE OF ETHICS AND COMPLIANCE |

|

Percentage of employees completing annual training of Code of Ethics and Compliance |

Number of confirmed corruption incidents |

Number of channels or mechanism for employee feedback and grievance redressal |

Number of whistleblower reports received and resolved |

Number of audits conducted to assess the compliance to the policy on Anti-corruption (anti bribery, conflict of interest, fraud prevention, anti-money laundering), Insider trading, Stock tipping, gift and hospitality, posh, and fair competition |

Resolution time for employee grievances (average days) |

RISK MANAGEMENT |

|

Percentage of identified risks with mitigation strategies |

Number of cybersecurity breaches reported |

Percentage of critical sites with updated business continuity plans |

Number of annual audits on cyber security conducted |

Number of risk assessments conducted per year |

Percentage of operations covered by Information Security Management System (e.g. ISO27001) |

TRANSPARENCY AND REPORTING |

|

Publication of third party assured annual ESG reports |

Average resolution time for complaints of stakeholders |

The percentage increase in the average score in ESG rating by third party |

Number of incidents of non-compliance with regulations |

Number of governance policies implemented or updated |

Cases of litigation or legal disputes faced by the organization |

|

Fines or penalties paid due to governance lapses |

SUPPLIER ASSESSMENT |

|

Percentage of suppliers assessed and approved based on ESG criteria |

Instances of ESG-related non-compliance in supply chain |

Percentage increase in local sourcing (Domestic / within the district and neighboring districts) of raw material |

Compliance of the product with the regulations (e.g. REACH for EU) applicable to the country in which it is manufactured and marketed |

The percentage of suppliers underwent awareness program on sustainable procurement. |

|

The percentage of suppliers signed on the supplier code of conduct to ensure sustainable procurement |

|

Percentage of suppliers compliant with green procurement policies |

|

Percentage of supplier contracts into which ESG criteria have been integrated |

|

Percentage of suppliers taken targets on identified Key material topics |

|

Source: As conceived by the Author

By integrating these recommendations, collaboration, technology adoption, ESG transparency, strategic interventions, and robust KPI frameworks organizations can align profitability with environmental and social stewardship. In doing so, SSCM becomes not only a compliance requirement but also a strategic driver of competitiveness and resilience in the global marketplace.

Conceptual Framework of Sustainable Supply Chain Management:

Drawing on insights derived from the literature review, a conceptual framework for sustainable supply chain management is proposed, as illustrated in Fig. 4.

Implementation of Sustainable Procurement Policy and Supplier Code of Conduct |

Initiatives to reduce carbon footprint |

Collaboration on product |

common approaches based on shared values |

Implementation of comprehensive policies on Diversity, Equity and Inclusion (DEI) |

transportation vehicles/ships |

References:

- Ahmed, M. U., & Shafiq, A. (2022). Toward sustainable supply chains: impact of buyer's legitimacy, power and aligned focus on supplier sustainability performance. International Journal of Operations & Production Management, 42(3), 280-303. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJOPM-08-2021-0540.

- Ali, I., & Gölgeci, I. (2019). Where is supply chain resilience research heading? A systematic and co-occurrence analysis. International Journal of Physical Distribution & Logistics Management, 49(8), 793-815.

- Arroyo, L. Á. B., Barreto, C. A. D. L. S., Vasquez, O. B. S., & Nicola, R. J. V. (2023). The importance of Reverse Logistics and Green Logistics for Sustainability in Supply Chains. Journal of business and entrepreneurial study, 7(4), 46-72. https://journalbusinesses.com/index.php/revista/article/download/351/762.

- Bagheri, A., & Hjorth, P. (2007). A framework for process indicators to monitor for sustainable development: Practice to an urban water system. Environment, Development and Sustainability, 9(2), 143–161. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10668-005-9009-0.

- Carmagnac, L. (2021, July). Expanding the boundaries of SSCM: the role of non-traditional actors. In Supply Chain Forum: An International Journal (Vol. 22, No. 3, pp. 192-204). Taylor & Francis.

- Carter, C. R., & Liane Easton, P. (2011). Sustainable supply chain management: Evolution and future directions. International Journal of Physical Distribution & Logistics Management, 41(1), 46–62. https://doi.org/10.1108/09600031111101420.

- Carter, C. R., & Rogers, D. S. (2008). A framework of sustainable supply chain management: moving toward new theory. International Journal of Physical Distribution &Logistics Management, 38(5), 360–387. https://doi.org/10.1108/09600030810882816.

- Cervellin, F. M., Pegolo, M., & Delgado, M. (2024). Sustainability in the Consulting Industry. researchapi.cbs.dk/ws/portalfiles/portal/108050862/1854787_Masters_Thesis_Sustain ability_in_the_Consulting_Industry.

- Christmann, P. (2000). Effects of “best practices” of environmental management on cost advantage: The role of complementary assets. Academy of Management Journal, 43(4), 663–680. https://doi.org/10.2307/1556360

- Chvátalová, Z., & Šimberová, I. (2013). Analysis of ESG indicators for measuring enterprise performance. Acta Universitatis Agriculturae et Silviculturae Mendelianae Brunensis, 61(7), 2197–2204. https://doi.org/10.11118/actaun201361072197

- Colicchia, C., & Strozzi, F. (2012). Supply chain risk management: a new methodology for a systematic literature review. Supply chain management: an international journal, 17(4), 403-418. http://dx.doi.org/10.1108/13598541211246558.

- De Mendonca, T. R., & Zhou, Y. (2019). Environmental performance, customer satisfaction, and profitability: A study among large US companies. Sustainability, 11(19), 5418. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11195418.

- Deloitte(2024).CxO Sustainability report. https://www.deloitte.com/global/en/issues/climate/cxo-sustainability-report.html.

- Diabat, A., Kannan, D., & Mathiyazhagan, K. (2014). Analysis of enablers for implementation of sustainable supply chain management–A textile case. Journal of Cleaner Production, 83, 391–403. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2014.06.081.

- Dufvelin, H. (2018), Determining key performance indicators for environmental, social and governance [Master’s Thesis]. Lappeenranta University of Technology.

- Eccles, R. G., Ioannou, I., & Serafeim, G. (2014). The impact of corporate sustainability on organizational processes and performance. Management Science, 60(11), 2835– 2857. https://doi.org/10.1287/mnsc.2014.1984.

- Fahmi, M. A., Arifianti, R., Nurfauzia, F., & Rahardjo, J. (2023). Green Procurement Analysis Factors on the Procurement of Alternative Plastic Bag Substitutes in Modern Retail. Journal of Entrepreneurship, Management and Industry (JEMI), 6(1), 57-74. https://journal.bakrie.ac.id/index.php/JEMI/article/view/2418.

- Geissdoerfer, M., Savaget, P., Bocken, N. M., & Hultink, E. J. (2017). The Circular Economy–A new sustainability paradigm? Journal of cleaner production, 143, 757-768.https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/pdf/10.1111/jiec.13187?trk=public_post_comment-text.

- Govindan, K., Kaliyan, M., Kannan, D., & Haq, A. N. (2014). Barriers analysis for green supply chain management implementation in Indian industries using analytic hierarchy process. International Journal of Production Economics, 147, 555–568. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijpe.2013.08.018.

- Grimm, J. (2021). Engagement for supply chain sustainability: a guide. Cambridge Judge Business School. https://www.jbs.cam.ac.uk/wp-content/uploads/2021/07/guide-engagement-for-supply-chain-sustainability.pdf

- Grzybowska, K. (2012). Sustainability in the supply chain: analyzing the enablers. Environmental Issues in Supply Chain Management: New Trends and Applications, 25-40.

- Gualandris, J., & Kalchschmidt, M. (2016). Developing environmental and social performance:Theroleofsuppliers’ sustainabilityandbuyer–suppliertrust. International Journal ofProductionResearch,54(8), 2470–2486. https://doi.org/10.1080/00207543.2015.1106018

- Gualandris, J., Branzei, O., Wilhelm, M., Lazzarini, S., Linnenluecke, M., Hamann, R., Dooley, K. J., Barnett, M. L., & Chen, C. M. (2024). Unchaining supply chains: Transformative leaps toward regenerating social–ecological systems. Journal of Supply Chain Management, 60(1), 53-67.

- Gualandris, J., Golini, R., & Kalchschmidt, M. (2014). Do supply management and global sourcing matter for firm sustainability performance? [An international study]. Supply Chain Management, 19(3), 258–274. https://doi.org/10.1108/SCM-11-2013-0430.

- Gualandris, J., Klassen, R. D., Vachon, S., & Kalchschmidt, M. (2015). Sustainable evaluation and verification in supply chains: Aligning and leveraging accountability to stakeholders. Journal of Operations Management, 38, 1-13.

- Hänninen, S. (2023). Aligning supplier performance management with sustainable business strategy: Integrating CSR factors into supplier scorecards and performance management. https://urn.fi/URN:NBN:fi-fe20231031141979 [Master’s Thesis]. LUT University.

- Hassini, E., Surti, C., & Searcy, C. (2012). A literature review and a case study of sustainable supply chains with a focus on metrics. International journal of production economics, 140(1),69-82. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0925527312000576.

- Hegab, H., Shaban, I., Jamil, M., & Khanna, N. (2023). Toward sustainable future: Strategies, indicators, andchallengesforimplementingsustainableproduction systems. Sustainable MaterialsandTechnologies, 36,e00617. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.susmat. 2023.e00617.

- Kochina, K. (2019). A Study of Consumer Buying Behavior and Consumers' Attitude on Sustainable Production and Consumption in the Food and Beverage Sector. KAMK-University of Applied Sciences. https://www.theseus.fi/handle/10024/169610.

- Kumar, S., Teichman, S., & Timpernagel, T. (2012). A green supply chain is a requirement for profitability. International Journal of Production Research, 50(5), 1278–1296. https://doi.org/10.1080/00207543.2011.571924.

- Lambert, Douglas & Enz, Matias. (2017). Issues in Supply Chain Management: Progress and Progress and potential. Industrial marketing management, 62, 1-16. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.indmarman.2016.12.002.

- Lee, S., & Kim, Y. J. (2024). Analyzing Factors That Affect Korean B2B Companies’ Sustainable Performance. Sustainability, 16(5), 1719.

- Li, J., Fang, H., & Song, W. (2019). Sustainable supplier selection based on SSCM practices: A rough cloud TOPSIS approach. Journal of cleaner production, 222, 606-621.

- Mahler, D., & Kearney, A. T. (2007). The sustainable supply chain. Supply Chain Management Review, 11(8), 59-60.

- Morali, O., Searcy, C., (2011). Building Sustainability into Supply Chain Management in Canadian Corporations. Canadian Purchasing Research Foundation, O’Rourke, D. (2014). The science of sustainable supply chains. Science, 344(6188), 1124-1127.

- Omar, A. O. (2020). Effect Of Circular Economy Practices On Supply Chain Performance Of Chemical And Allied Sector Firms In Kenya (Doctoral dissertation, University of Nairobi).

- Pagell, M., & Shevchenko, A. (2014). Why research in sustainable supply chain management should have no future. Journal of supply chain management, 50(1), 44-55. potential. Industrial MarketingManagement, 62. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.indmarman.2016.12.002.

- PCBL Chemical Limited (2024). Annual Reports. https://www.pcblltd.com/investor-relation/financials/annual-reports).

- Prajapati, H., Kant, R., & Shankar, R. (2019). Prioritizing the solutions of reverse logistics implementation to mitigate its barriers: A hybrid modified SWARA and WASPAS approach. Journal of Cleaner Production, 240, 118219. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2019.118219.

- PwC. (2024). Building Sustainable Chemical Manufacturing in India through Innovation, Integration and Incentives. Proceedings of 6th ICC Sustainability Conclave. https://www.pwc.in/assets/pdfs/building-sustainable-chemical-manufacturing-in-india-through-innovation-integration-and-incentives.pdf.

- Sadiku, M. N., Ashaolu, T. J., Adekunte, S. S., & Musa, S. M. (2021). Green accounting: A primer. Internationaljournalofscientificadvances,2(1), 60-62. https://www.ijscia.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/02/Volume2-Issue1-Jan-Feb-No.42-60 62.pdf.

- Saurage-Altenloh, S. M. (2017). The measured influence of supplier CSR on brand performance expectations in B2B relationships ([Doctoral Dissertation]. Capella University).

- Schumann, M. (Ed.). (2010). Multikonferenz Wirtschaftsinformatik 2010: Göttingen, 23.-25. Februar 2010; Kurzfassungen der Beiträge. Universitätsverlag Göttingen.

- Searcy, C., Karapetrovic, S., & McCartney, D. (2009). Designing corporate sustainable development indicators: Reflections on a process. Environmental Quality Management, 19(1), 31-42.

- Seuring, S., & Müller, M. (2008). From a literature review to a conceptual framework for sustainable supply chain management. Journal of cleaner production, 16(15), 1699- 1710.

- Srivastava, S.K., 2007. Green supply-chain management: a state-of-the-art literature review. International Journal of Management Reviews. 9 (1), 53–80.