Subscribe now to get notified about IU Jharkhand journal updates!

Institutional Shareholding in Mid-Cap Companies in India: The Interplay of CEO Characteristics, Industry Dynamics, and Corporate Governance

Abstract :

India’s rise as the world’s fifth-largest and fastest-growing major economy underscores the growing significance of mid-cap companies. These firms blend the resilience of large corporations with the agility of smaller ones, making them vital to the nation’s economic progress. This study examines how CEO characteristics, sector-specific factors, and effective corporate governance impact institutional shareholding. CEO characteristics like tenure, qualifications, and national ownership shape investor perception, while macroeconomic factors and strong governance practices further influence investment decisions in this dynamic market.This research is based on a detailed analysis of mid-cap companies listed on the Bombay Stock Exchange (BSE). It uses a balanced panel dataset covering 5 years from 2018 to 2023.

The study finds that institutional investors in India’s mid-cap segment are significantly influenced by CEO attributes, industry-specific financial conditions, and governance standards. Firms led by experienced and well-qualified CEOs with strong governance practices tend to attract more institutional investment. Furthermore, sectoral financial indicators are found to moderate these effects, underscoring the complexity of investment decisions in this segment.

Keywords :

Institutional Investment, Mid-cap Firms, Corporate Governance, CEO Characteristics, Macroeconomic factors, Indian Equity Market.Introduction

Mid-cap companies in India represent a vital segment of the corporate ecosystem, positioned between the stability of large-cap firms and the agility of small-cap enterprises. These firms contribute significantly to economic growth through innovation, employment, and sectoral diversification (Balasubramanian, Black, & Khanna, 2010). As institutional investors—both domestic and foreign—increase their focus on this segment, their role extends beyond capital infusion to influencing governance, transparency, and long-term strategy (Aggarwal, Erel, Ferreira, & Matos, 2020; Narayan & Thenmozhi, 2019).

Institutional shareholding patterns in mid-cap firms are shaped by several interrelated factors. CEO characteristics—including duality ,education, tenure, domain expertise, and prior leadership experience—serve as signals of strategic competence and governance strength, impacting investor confidence (Bhagat, Bolton, & Subramanian, 2010; Singh & Kansal, 2021). These effects are especially pronounced in the BFSI sector, where leadership quality directly affects compliance, risk, and innovation.

Additionally, industry-specific dynamics such as regulatory intensity, and competitive pressures influence how institutional investors perceive mid-cap firms. Strong corporate governance mechanisms—including board independence, gender diversity, and promoter shareholding transparency—further strengthen a firm’s appeal (Jensen & Meckling, 1976; Adams & Ferreira, 2009).

This study examines the interplay between CEO characteristics, industry factors, and governance practices in shaping institutional shareholding in India’s mid-cap BFSI sector. By integrating agency, stewardship, and signaling theories, the research offers nuanced insights into investor behavior and governance priorities in a rapidly evolving market.

Literature Review

In India’s dynamic BFSI (Banking, Financial Services, and Insurance) sector, institutional investors have emerged as pivotal agents of corporate discipline. Beyond providing capital, they demand enhanced transparency, regulatory compliance, and long-term value creation, particularly from mid-cap firms that straddle rapid growth and evolving governance maturity. Prior literature underscores their significance in shaping governance structures and firm performance (Balasubramanian, Black, & Khanna, 2010; Sarkar & Sarkar, 2000; Shleifer &Vishny, 1997). Narayan and Thenmozhi (2019) affirm that institutional ownership in India’s mid-cap firms promotes greater transparency and valuation efficiency, reinforcing their role in stabilizing the sector and enhancing stakeholder accountability.

CEO Characteristics and Strategic Signaling

CEO attributes—particularly duality,educational background, age, and tenure tc. —are critical to shaping firm strategy, governance efficacy, and institutional investor perception. CEO duality, where the CEO also chairs the board, continues to polarize governance discourse. While it can streamline decision-making (Finkelstein &D’Aveni, 1994), it may also compromise board independence and oversight (Brickley, Coles, & Jarrell, 1997; Daily & Dalton, 1997). Within Indian BFSI firms, Gupta and Sharma (2020) highlight that the governance environment—especially board independence—mediates the impact of CEO duality on firm performance and investor response.

The CEO's educational pedigree acts as a strategic signal of governance acumen and market credibility. Advanced degrees, particularly those with global or financial specialization, are associated with better strategic foresight and risk oversight (Bhagat, Bolton, & Subramanian, 2010). Singh and Kansal (2021) find that Indian firms led by highly educated CEOs tend to attract stable institutional ownership, especially in BFSI where technical and regulatory demands are elevated. Similarly, Custódio and Metzger (2014) link financial expertise among CEOs with superior capital allocation and investor confidence.

Gender Diversity in Corporate Boards

Gender diversity within boards is increasingly recognized not merely as a compliance mandate but as a governance enhancer. Diverse boards contribute cognitive richness, enhance deliberative quality, and promote stakeholder inclusivity (Adams & Ferreira, 2009; Terjesen, Sealy, & Singh, 2009). In India, Sharma and Verma (2022) observe that gender-diverse boards improve ethical oversight and reduce risk opacity, strengthening investor confidence in sectors with heightened scrutiny such as BFSI.

Independent Directors and Board Effectiveness

Independent directors function as vital governance intermediaries in India’s promoter-centric ownership environment. Grounded in agency theory (Jensen & Meckling, 1976), their presence addresses asymmetries between controlling promoters and minority shareholders. Their ability to foster board transparency and strategic accountability is well-documented (Balasubramanian et al.,

2010; Ghosh, 2010). Institutional investors consistently prioritize firms with strong board independence, seeing it as indicative of governance resilience (Sarkar & Sarkar, 2000).

Promoter Shareholding: Control vs. Accountability

Promoter ownership is a defining feature of Indian firms and presents a nuanced governance paradox. While moderate promoter holding can indicate strategic alignment and long-term vision, excessive concentration may lead to entrenchment and governance opacity (Kumar & Zattoni, 2018). La Porta et al. (1999) argue that in emerging markets, such concentrated control often weakens institutional protections. In the BFSI context, where trust and regulatory credibility are paramount, promoter influence must be balanced with board independence and investor protection mechanisms.

Regulatory Compliance and Institutional Sentiment

In the BFSI sector, adherence to regulatory norms significantly shapes investor sentiment. Firms with histories of SEBI observations, audit delays, or compliance breaches are often penalized through reduced institutional holdings. Mishra and Mohanty (2017) document that institutional investors respond swiftly to regulatory red flags, recalibrating their exposure to mitigate reputational and financial risk. Conversely, firms demonstrating transparent and proactive compliance frameworks often command valuation premiums (Aggarwal, Erel, Ferreira, & Matos, 2020). Such behavior aligns with signaling theory, where regulatory integrity functions as a market signal of managerial credibility and operational discipline.

Institutional Shareholding, Tobin’s Q, and Firm Valuation

Tobin’s Q—defined as the ratio of a firm's market value to the replacement cost of its assets—serves as a robust proxy for market perception, innovation potential, and strategic efficiency (Tobin, 1969). Morck, Shleifer, and Vishny (1988) argue that higher Tobin’s Q attracts institutional investors due to its correlation with governance and capital productivity. In India, Raghunandan and Rajgopal (2019) link elevated Tobin’s Q with strong board oversight and regulatory adherence, particularly in mid-cap BFSI firms. Agency theory supports this view, positioning institutional ownership as a corrective force aligning firm actions with shareholder value (Jensen & Meckling, 1976).

Theoretical Underpinnings

This study is anchored in three theoretical frameworks:

Agency Theory (Jensen & Meckling, 1976): Highlights the principal-agent problem and positions institutional investors and independent directors as mechanisms to align interests.

Signaling Theory (Spence, 1973): Posits that CEO traits (e.g., education, gender) and firm-level practices (e.g., compliance, board diversity) serve as credible market signals to attract institutional capital.

Stewardship Theory (Davis, Schoorman, & Donaldson, 1997): Offers a counterpoint by suggesting that CEOs, particularly in dual roles, may act as stewards of firm value—provided they are motivated by trust and accountability.

These theories provide an integrated lens to evaluate governance complexity in India’s evolving mid-cap BFSI ecosystem.

Gaps in Literature and Study Contribution

Despite increasing attention to corporate governance in emerging markets, mid-cap BFSI firms in India remain underexplored. Existing research tends to either concentrate on large-cap companies or analyze governance mechanisms in isolation. This study addresses these gaps by investigating the intersection of CEO attributes (duality, education, gender), board structure (independence, promoter holding), and regulatory compliance in shaping institutional shareholding and Tobin’s Q across 14 mid-cap BFSI firms from 2018 to 2024. The findings are expected to enrich governance literature, inform investor strategy, and support policy frameworks promoting transparency and sustainable value creation in emerging financial markets.

Data and Methodology

The core objective of this research is to explore the combined effect of CEO traits—such as tenure, age, education, and professional background—and corporate governance parameters, including board independence, audit mechanisms, and promoter shareholding, on the extent and consistency of institutional ownership in mid-cap Indian firms. The study seeks to uncover meaningful trends and potential causal linkages that may explain why institutional investors favor certain firms and how their involvement shapes corporate direction.

This analysis spans the years 2018 to 2024 and focuses on mid-cap companies, which occupy a crucial space in India’s capital markets—offering a balance between the resilience of large-cap firms and the agility of small-cap players. The research sample consists of 14 mid-cap entities from the BFSI sector: 8 banks, 3 NBFCs, 2 insurance providers, and 1 asset management company, all selected from the NSE’s Nifty Midcap 150 Index.

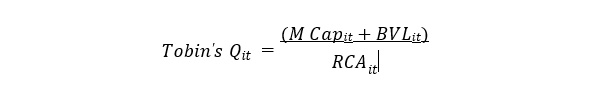

Firm value in this study is represented using Tobin’s Q, serving as an indicator of market expectations regarding a firm’s future performance.This value is estimated as :

Here, “i” represents the individual firm in the sample, while “t” corresponds to the specific year of observation.M Capit represents the market Capitalisation for each of the firms. BVL represents the book value firm, and RCAit represents the total replacement cost of the assets. These values are estimated for each firm for each of the years from 2018 – 2024.

The study uses Panel data regression as it allows for the simultaneous capture of both cross-sectional heterogeneity and time-series dynamics. It is ideal for studying the evolution and stability of institutional shareholding, allowing us to see how CEO characteristics and governance influence investment decisions over time, not just at one point.

Table No 1

Variables under the study

Variables |

Description |

Tobin’s Q |

Tobin’s Q serves as an indicator of a company’s market performance, measured by dividing the firm’s market value by the cost to replace its assets. It reflects how investors view the firm’s potential for future |

Institutional Shareholding |

Represents the percentage of a company’s equity held by institutional |

Gender Diversity |

Measured by the presence of female directors on the board, this variable captures diversity in leadership and its potential influence on |

Regulatory Flag |

A binary variable indicating whether the company has been flagged for regulatory concerns (e.g., SEBI observations or compliance issues), |

CEO Duality |

When the same person holds both the CEO and Chairperson positions, |

CEO Education |

Categorized based on the highest educational qualification of the CEO |

The above discussion leads to the formulation of the following Null hypotheses of the study:

H01: There is no significant impact of Firm value on institutional shareholding.

H02: There is no significant impact of board gender diversity on institutional ownership.

H03: There is no significant relationship between institutional shareholding and recent regulatory flags.

H04: There is no significant impact of CEO duality on firm value.

H05: There is no significant impact of CEO education level (Tier 1) on firm value.

Empirical Analysis, Results, and Discussion

Table * presents the summary statistics of the chosen variables covering the period from 2018 to 2024.A Tobin Q's value greater than 1 implies that the market value of assets surpasses the book value of its assets. However, with the mean value close to 1, it indicates a balanced or equilibrium valuation between a company's (or market's) market value and the replacement cost of its assets:

Table * details the descriptive statistics for the variables used in the study.

Table No 2

Hypothesis Testing

Variable |

Obs |

Mean |

Std. Dev. |

Min |

Max |

Institutional Shareholding (%) |

98 |

42.61 |

18.55 |

11.8 |

87.6 |

CEO Tier 1 Education (0/1) |

98 |

0.79 |

0.41 |

0 |

1 |

CEO Tenure (years) |

98 |

8.28 |

6.79 |

1 |

28 |

CEO Age (years) |

98 |

58.07 |

7.56 |

38 |

77 |

CEO Duality (0/1) |

98 |

0.28 |

0.45 |

0 |

1 |

Recent Regulatory Flag (0/1) |

98 |

0.21 |

0.41 |

0 |

1 |

Board Strength (No. of |

98 |

10.41 |

1.13 |

8 |

12 |

Women Directors (Count) |

98 |

2.72 |

0.73 |

1 |

5 |

CEO Education (Scale) |

98 |

9.11 |

3.88 |

1 |

15 |

Market Cap (Cr) |

98 |

48,497.58 |

56,830.13 |

4,441.2 |

335,090 |

Market Value of Debt (Cr) |

98 |

10,162.17 |

8,018.67 |

120 |

41,000 |

Book Value (Cr) |

98 |

7,046.68 |

12,565.51 |

306.7 |

70,149 |

Replacement Cost (Cr) |

98 |

20,655.43 |

29,466.87 |

6,500 |

180,543 |

Tobin's Q |

98 |

3.75 |

3.78 |

0.72 |

24.97 |

Table No 3

Hypothesis Testing

Hypothesis |

Dependent Variable |

Independent Variable |

Coefficient |

P-value |

Result |

H1: Firm value has no |

Institutional Shareholding |

Tobin's Q |

0.045 |

0.876 |

Insignificant |

H2: Board gender diversity significantly increases institutional ownership. |

Institutional Shareholding |

Women Director (%) |

2.52 |

0.066 |

Significant (10% level) |

H3: |

Institutional Shareholding |

Recent Regulatory Flag PCAS |

1.431 |

0.462 |

Insignificant |

H4: CEO |

Tobin’s Q |

CEO Duality (0 |

0.6913 |

0.617 |

Insignificant |

H5: CEO |

Tobin’s Q |

Tier 1 CEO Education |

0.1658 |

0.894 |

Insignificant |

The study investigates key determinants of institutional shareholding and firm value in midcap BFSI firms using fixed-effects panel regressions and impulse response analysis.

The findings reveal that firm value (measured via Tobin's Q) does not significantly influence institutional shareholding, and CEO characteristics such as duality and Tier 1 education background also show no significant effect on firm performance. Board gender diversity shows a marginally significant positive effect on institutional shareholding, suggesting some institutional preference for gender-diverse boards.

Table No 4

Regression Equations by Hypothesis

Hypothesis |

Regression Equation |

H01: |

InstiShareholding_it= α_i + β1 * TobinQ_it + u_it |

H02: |

InstiShareholding_it= α_i + β1 * WomenDirector%_it + u_it |

H03: |

InstiShareholding_it = α_i + β1 * RecentRegulatoryFlagPCAS_it + u_it |

H04: |

TobinQ_it= α_i + β1 * CEOduality_it + u_it |

H05: |

TobinQ_it = α_i + β1 * CEOEducationTier1_it + u_it |

Limitations of the Study

This study, while insightful, is subject to certain limitations. The sample is limited to 14 mid-cap BFSI firms in India from 2018–2024, which may restrict generalizability. The reliance on secondary data omits qualitative aspects such as boardroom dynamics and investor sentiment. Additionally, using Tobin’s Q as a proxy for firm value, though standard, may not fully reflect sector-specific nuances or market fluctuations. Finally, the study is observational, limiting causal inferences between governance variables and institutional ownership. Future research could address these gaps by expanding the dataset, incorporating qualitative insights, or applying advanced econometric models.

Scope of Further Study

This study opens several meaningful avenues for future research. A longitudinal approach could uncover how institutional shareholding patterns evolve through economic cycles and leadership changes in mid-cap firms. Further exploration into qualitative CEO traits—such as integrity, strategic clarity, digital adaptability, boardroom behavior, and even public image—can offer deeper insight into investor decision-making. Comparative studies across emerging economies may also shed light on where India’s mid-cap landscape aligns or diverges in terms of governance and investment trends. Additionally, as mid-cap sectors undergo digital disruption, embrace green transitions, and respond to regulatory changes, examining these industry dynamics will add valuable perspective to institutional investment behavior.

References

- Adams, R. B., & Ferreira, D. (2009). Women in the boardroom and their impact on governance and performance. Journal of Financial Economics, 94(2), 291–309. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jfineco.2008.10.007

- Aggarwal, R., Erel, I., Ferreira, M., & Matos, P. (2020). Institutional investment around the world.Review of Financial Studies, 33(12), 5508–5559. https://doi.org/10.1093/rfs/hhaa056

- Balasubramanian, N., Black, B. S., & Khanna, V. S. (2010). The relation between firm-level corporate governance and market value: A case study of India. Emerging Markets Review, 11(4), 319–340. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ememar.2010.05.001

- Bhagat, S., Bolton, B., & Subramanian, A. (2010). CEO education, CEO turnover, and firm performance. Indian School of Business Working Paper Series.

- Brickley, J. A., Coles, J. L., & Jarrell, G. (1997). Leadership structure: Separating the CEO and chairman of the board. Journal of Corporate Finance, 3(3), 189–220. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0929-1199(96)00013-2

- Chakrabarti, R., Megginson, W. L., & Yadav, P. K. (2008). Corporate governance in India. Journal of Applied Corporate Finance, 20(1), 59–72. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1745-6622.2008.00180.x

- Custódio, C., & Metzger, D. (2014). Financial expert CEOs: CEO's work experience and firm's financial policies. Journal of Financial Economics, 114(1), 125–154. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jfineco.2014.06.002

- Daily, C. M., & Dalton, D. R. (1997). CEO and board chair roles held jointly or separately: Much ado about nothing? Academy of Management Executive, 11(3), 11–20. https://doi.org/10.5465/ame.1997.9709231664

- Davis, J. H., Schoorman, F. D., & Donaldson, L. (1997). Toward a stewardship theory of management. Academy of Management Review, 22(1), 20–47. https://doi.org/10.5465/amr.1997.9707180258

- Finkelstein, S., &D’Aveni, R. A. (1994). CEO duality as a double-edged sword: How boards of directors balance entrenchment avoidance and unity of command. Academy of Management Journal, 37(5), 1079–1108. https://doi.org/10.5465/256667

- Ganguli, S. K., & Agrawal, S. (2009). Ownership structure and firm performance: A study on Indian firms. ICFAI Journal of Applied Finance, 15(12), 5–17.

- Ghosh, S. (2010). Firm ownership, corporate governance and firm performance: Evidence from India. Journal of Corporate Governance, 10(5), 411–425. https://doi.org/10.1108/14720701011085562

- Gupta, P., & Sharma, A. K. (2020). Do CEO characteristics explain firm performance in India?Journal of Strategy and Management, 13(2), 281–297. https://doi.org/10.1108/JSMA-09-2019-0156

- Hambrick, D. C., & Mason, P. A. (1984). Upper echelons: The organization as a reflection of its top managers. Academy of Management Review, 9(2), 193–206. https://doi.org/10.5465/amr.1984.4277628

- Jain, T., & Jamali, D. (2016). Looking inside the black box: The effect of corporate governance on corporate social responsibility. Corporate Governance: An International Review, 24(3), 253–273. https://doi.org/10.1111/corg.12154

- Jensen, M. C., & Meckling, W. H. (1976). Theory of the firm: Managerial behavior, agency costs and ownership structure. Journal of Financial Economics, 3(4), 305–360. https://doi.org/10.1016/0304-405X(76)90026-X

- Kumar, P., &Zattoni, A. (2018). Ownership structure and corporate governance in India. In Clarke, T., & Branson, D. M. (Eds.), The SAGE Handbook of Corporate Governance (pp. 308–328). SAGE Publications.

- La Porta, R., Lopez-de-Silanes, F., & Shleifer, A. (1999). Corporate ownership around the world.Journal of Finance, 54(2), 471–517. https://doi.org/10.1111/0022-1082.00115

- Li, F., Li, T., & Minor, D. (2016). CEO power, corporate governance, and firm value. Journal of Financial Economics, 120(2), 299–315. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jfineco.2016.01.005

- Mishra, S., & Mohanty, P. (2017). Does corporate governance affect firm valuation in India? Evidence from firm-level panel data. Journal of Financial Management & Analysis, 30(1), 34–45.

- Morck, R., Shleifer, A., &Vishny, R. W. (1988). Management ownership and market valuation: An empirical analysis. Journal of Financial Economics, 20, 293–315. https://doi.org/10.1016/0304-405X(88)90048-7

- Mukherjee, S., & Sen, D. (2022). CEO busyness and firm performance: Evidence from Indian listed firms. Asian Journal of Business Ethics, 11(1), 21–38. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13520-021-00135-6

- Narayan, P. K., & Thenmozhi, M. (2019). Institutional investors and corporate governance in India: A review and synthesis. Indian Journal of Corporate Governance, 12(2), 159–180. https://doi.org/10.1177/0974686219883733

- Raghunandan, K., & Rajgopal, S. (2019). Do institutional investors influence corporate governance and firm performance in India? Accounting Horizons, 33(2), 145–161. https://doi.org/10.2308/acch-52304

- Sarkar, J., & Sarkar, S. (2000). Large shareholder activism in corporate governance in developing countries: Evidence from India. International Review of Finance, 1(3), 161–194. https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-2443.00008

- Sarkar, S., & Sarkar, J. (2009). Corporate governance in India: Evolution and challenges. ICRIER Working Paper No. 249. https://icrier.org/pdf/Working_Paper_249.pdf

- Sharma, S., & Verma, S. (2022). Board gender diversity and firm performance: Empirical evidence from Indian BFSI firms. Asian Journal of Accounting Research, 7(1), 15–31. https://doi.org/10.1108/AJAR-11-2020-0101

- Shleifer, A., &Vishny, R. W. (1997). A survey of corporate governance. Journal of Finance, 52(2), 737–783. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-6261.1997.tb04820.x

- Singh, A., & Gaur, A. (2021). Digital transformation and institutional investment: Evidence from India. Journal of Business Research, 134, 789–798. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2021.06.020

- Singh, R., & Kansal, R. (2021). CEO education and firm performance: Empirical evidence from Indian banking sector. Indian Journal of Economics and Business, 20(3), 179–196.

- Spence, M. (1973). Job market signaling. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 87(3), 355–374. https://doi.org/10.2307/1882010

- Terjesen, S., Sealy, R., & Singh, V. (2009). Women directors on corporate boards: A review and research agenda. Corporate Governance: An International Review, 17(3), 320–337. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8683.2009.00742.x

- Tobin, J. (1969). A general equilibrium approach to monetary theory. Journal of Money, Credit and Banking, 1(1), 15–29. https://doi.org/10.2307/1991374

- Zattoni, A., & Judge, W. Q. (2012). Corporate governance and initial public offerings: An international perspective. Corporate Governance: An International Review, 20(2), 117–120. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8683.2012.00901.x