Subscribe now to get notified about IU Jharkhand journal updates!

Traditional Knowledge-Based Entrepreneurship Measurement in Kashmir Valley An Indian Knowledge System Perspective

Abstract :

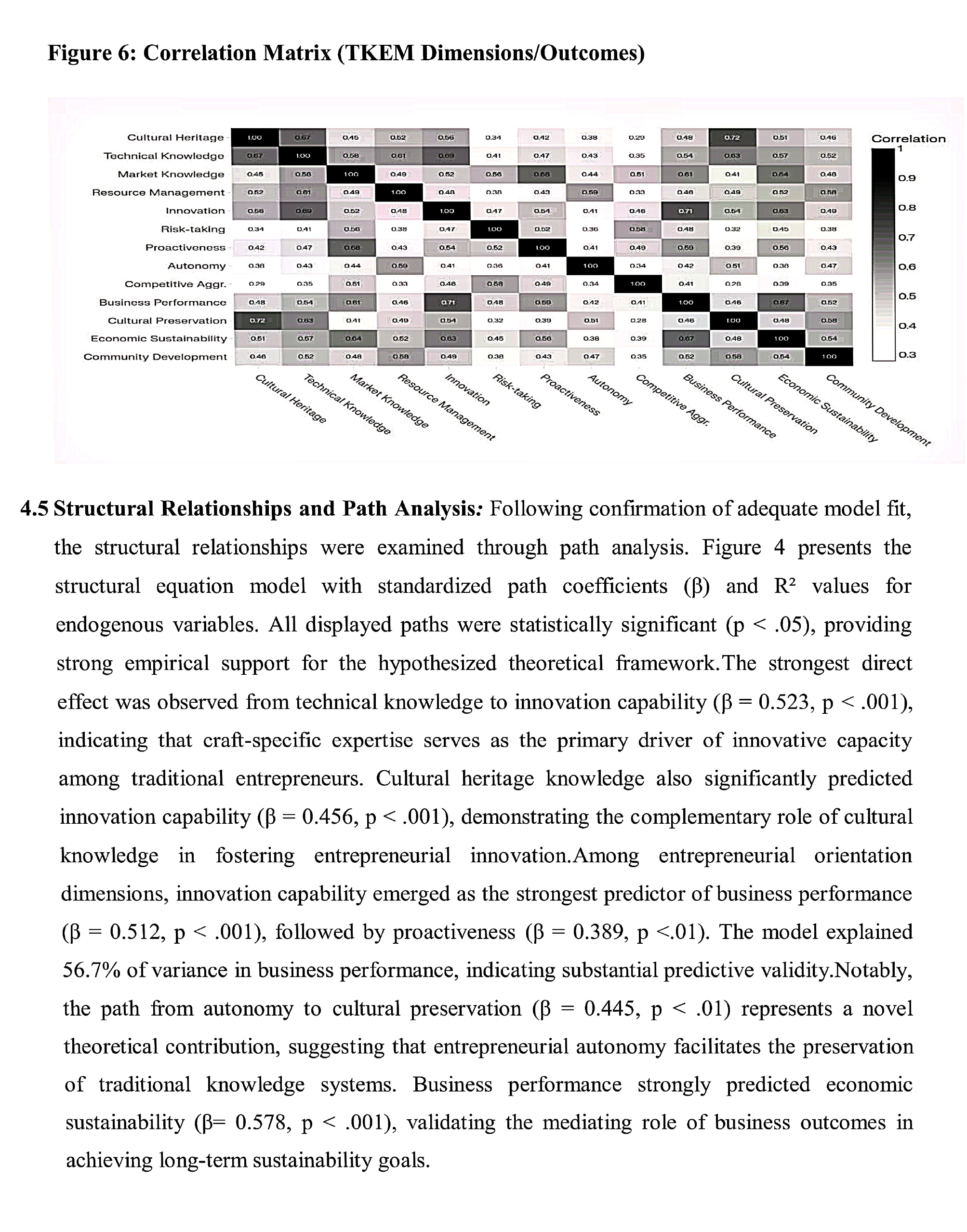

This study addresses the critical void in entrepreneurship research by developing and validating the Traditional Knowledge-Based Entrepreneurship Measurement (TKEM) scale tailored to the Kashmir Valley within India’s Indigenous Knowledge System (IKS). Drawing on a mixed- methods, multi-phase instrument construction process—including literature synthesis, expert interviews (n = 15), focus groups (n = 3), and content validation (CVR threshold ≥ 0.62)—an initial 85-item pool was refined to 45 items and pilot tested (n = 50) via exploratory factor analysis, yielding a 32-item, nine-factor structure. A main sample (n = 350) and an independent validation sample (n = 200) completed structured questionnaires on 5-point Likert scales. Confirmatory factor analysis (χ²/df = 2.19, CFI = 0.924, TLI = 0.918, RMSEA = 0.059, SRMR = 0.048) substantiated the nine-factor model. Reliability indices (Cronbach’s α = .785–.892; composite reliability = .792–.897) and validity evidence (AVE ≥ .50; discriminant validity via AVE square-root comparisons) confirmed scale robustness. The TKEM scale offers scholars and policymakers a rigorously tested tool for quantifying traditional knowledge dimensions (cultural heritage, technical craft, market, resource management) and entrepreneurial orientation (innovation, risk-taking, proactiveness, autonomy, competitive aggressiveness), thereby supporting sustainable rural development and cultural preservation in Kashmir

Keywords :

Traditional Knowledge, Kashmir Valley, Entrepreneurship Measurement, Indian Knowledge System, Scale DevelopmentIntroduction

The Kashmir Valley has long been celebrated for its centuries-old artisanal traditions—Pashmina weaving, papier-mâché artistry, saffron cultivation, and wood carving—which embody rich bodies of local knowledge passed through generations (Towseef Mohi Ud Din, 2015; Maheshwari, 2024).

Despite widespread recognition of the valley’s cultural capital, empirical research lacks a standardized framework for measuring how traditional knowledge informs entrepreneurial behavior and business outcomes.

Traditional Knowledge Systems (TKS) confer both technical skills and community-based learning advantages that can drive innovation and market differentiation (Cheteni & Umejesi, 2024; Maheshwari, 2024).

However, extant entrepreneurial orientation scales (e.g., Lumpkin & Dess, 1996; Clark et al., 2025) do not capture the unique dimensions of TKS.

This gap constrains evidence-based policy interventions aimed at enhancing socio-economic resilience in conflict-affected regions (Cheteni & Umejesi, 2024).

1.1 Research Questions & Objectives

What are core dimensions of traditional knowledge-based entrepreneurship in Kashmir Valley?

How can these be measured reliably and validly?

What role does Indian Knowledge System play in supporting and sustaining such entrepreneurship?

A validated scale will facilitate evidence-based policy and practice, enhancing livelihoods, preserving culture, and guiding sustainable rural development.

2. Literature Review

Indigenous knowledge systems (IKS) encompass the deeply rooted, context-specific practices, beliefs, and skills that communities develop over generations to interact sustainably with their environments (WIPO, 2020).

These systems function as repositories of tacit and explicit knowledge that often remain undervalued by formal economic frameworks, despite their potential to foster innovation and resilience in rural contexts (Maheshwari, 2024).

In the Kashmir Valley, traditional craft sectors—such as Pashmina weaving, papier-mâché artistry, and saffron cultivation—illustrate the symbiotic relationship between cultural heritage and economic livelihoods.

Artisans leverage ancestral design motifs, community-based learning networks, and resource management practices to generate unique value propositions in domestic and international markets (Towseef Mohi Ud Din, 2015; Majeed & Muzaffar, 2025).

Scholars have argued that conventional entrepreneurial orientation (EO) measures—focusing on innovativeness, risk-taking, proactiveness, autonomy, and competitive aggressiveness—insufficiently capture the culturally embedded dimensions of entrepreneurship in Indigenous and traditional knowledge communities (Lumpkin & Dess, 1996; Clark et al., 2025).

Lumpkin and Dess’s (1996) seminal EO framework remains influential, yet its unmodified application risks omitting critical aspects of tacit knowledge transmission, ethical stewardship, and community cohesion that underpin traditional ventures.

Recent research thus advocates for contextually grounded scale development, integrating deductive literature synthesis with inductive stakeholder input to ensure both theoretical rigor and cultural salience (Cheteni & Umejesi, 2024; Clark et al., 2025).

The resource-based view (RBV) provides a theoretical lens for understanding how unique, non-replicable knowledge resources confer sustainable competitive advantage (Barney, 1991).

Within this paradigm, traditional knowledge—ranging from craft-specific technical expertise to ecological stewardship practices—represents strategic assets that can drive innovation and market differentiation (Maheshwari, 2024).

Yet empirical operationalization of these assets in entrepreneurship research remains nascent.

For instance, while Cheteni and Umejesi (2024) examined cultural tourism in South African rural communities, they emphasized the need for validated instruments to quantify Indigenous knowledge impacts on business performance.

Psychometric literature underscores best practices for scale development, including rigorous content validity assessment, exploratory factor analysis (EFA), confirmatory factor analysis (CFA), and reliability testing (Hinkin, 1998; Lawshe, 1975).

Hinkin (1998) advocates combining expert reviews with pilot testing to refine item pools, while Lawshe’s (1975) Content Validity Ratio (CVR) method provides objective criteria for item retention.

Fornell and Larcker’s (1981) guidelines for assessing convergent and discriminant validity remain standard in evaluating construct validity.

In traditional knowledge entrepreneurship research, few studies have systematically applied these psychometric protocols.

Clark et al. (2025) recently developed an individual entrepreneurial orientation scale, demonstrating the importance of context-specific item wording and validation in diverse samples.

Likewise, studies on artisanal sectors in Kashmir (e.g., Towseef Mohi Ud Din, 2015; Majeed & Muzaffar, 2025) have provided rich qualitative insights but lacked standardized measurement instruments.

This gap highlights the urgency of creating robust, culturally adapted scales.

Furthermore, the role of entrepreneurial autonomy in cultural preservation has received scant attention.

Autonomy—characterized by self-directed decision-making—traditionally links to strategic flexibility in EO research (Lumpkin & Dess, 1996) but seldom to heritage conservation outcomes.

The present study’s inclusion of autonomy as a predictor of cultural preservation responds to calls for expanding EO frameworks to address socio-cultural goals alongside economic objectives (Rauch et al., 2009; UNESCO, 2015).

Finally, the linkage between business performance and broader sustainability outcomes aligns with sustainable entrepreneurship literature, emphasizing economic viability, environmental stewardship, and social equity (Zahra & George, 2002).

By demonstrating that performance gains in traditional craft enterprises can translate into community development and ecological sustainability, recent work underscores the relevance of integrated measurement approaches (Nahapiet & Ghoshal, 1998; Barney, 1991).

Overall, the literature points to the strategic importance of traditional knowledge, the limitations of existing EO scales, and the necessity of rigorous psychometric scale development tailored to Indigenous contexts.

The TKEM scale responds by operationalizing four traditional knowledge dimensions and five entrepreneurial orientation factors through a validated nine-factor measurement model appropriate for the Kashmir Valley.

2.2 Research Gap

Indigenous and traditional knowledge systems constitute repositories of context-specific practices, values, and technical expertise integral to rural livelihoods (WIPO, 2020; Maheshwari, 2024).

Yet conventional entrepreneurial orientation frameworks remain insufficiently adapted to capture culturally embedded knowledge assets (Cheteni & Umejesi, 2024; Clark et al., 2025).

In Kashmir, artisans rely on ancestral design motifs, resource stewardship, and community networks, but systematic quantification of these dimensions remains absent.

The TKEM scale addresses this shortfall by merging deductive literature mapping with inductive stakeholder input, ensuring content validity and cultural relevance (Hinkin, 1998; Lawshe, 1975).

2.3 Theoretical & Conceptual Framework

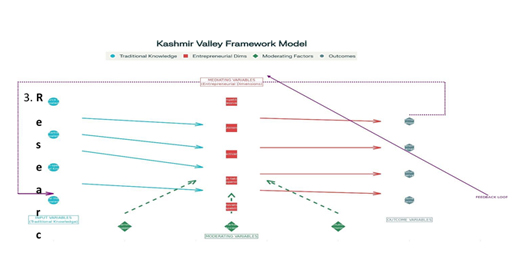

The conceptual framework posits that cultural heritage, technical craft knowledge, market awareness, and resource management mediate entrepreneurial orientation dimensions.

Outcomes include business performance, cultural preservation, economic sustainability, and community development, moderated by governmental and institutional support.

Figure 1: Conceptual Framework Diagram

1. Methodology

1.1 Research Design

A cross-sectional, quantitative approach was used, targeting traditional craft entrepreneurs in Kashmir Valley.

Three-stage sampling (purposive, snowball, stratified) ensured inclusion of diverse crafts.

1.2 Scale Development

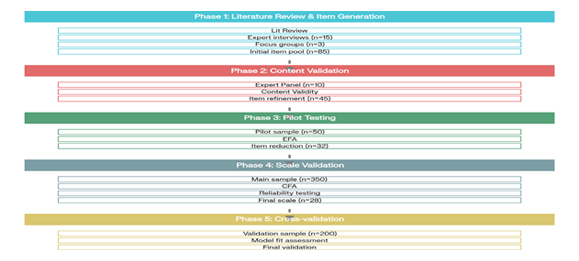

A systematic multi-phase methodology was implemented:

Figure 2: TKEM Scale Development Flowchart

1.3 Instrument Construction

The Traditional Knowledge-Based Entrepreneurship Measurement (TKEM) scale was developed through a rigorous, multi-phase process designed to ensure both theoretical coherence and empirical robustness. Initially, a comprehensive literature review identified key constructs drawn from Indigenous knowledge systems, entrepreneurship theory, and regional craft studies. This review informed the creation of an initial item pool of 85 statements, each formulated to capture specific dimensions of traditional knowledge (e.g., cultural heritage knowledge, technical craft knowledge) and entrepreneurial orientation (e.g., innovation capability, risk-taking propensity).

Next, expert interviews (n = 15) comprising senior scholars in management, cultural anthropology, and regional craft masters provided nuanced feedback on item relevance, clarity, and cultural appropriateness. Concurrently, three focus groups, each consisting of 8–10 Kashmiri artisans representing Pashmina, papier-mâché, wood carving, and saffron enterprises, evaluated the face validity of items and suggested vernacular refinements.

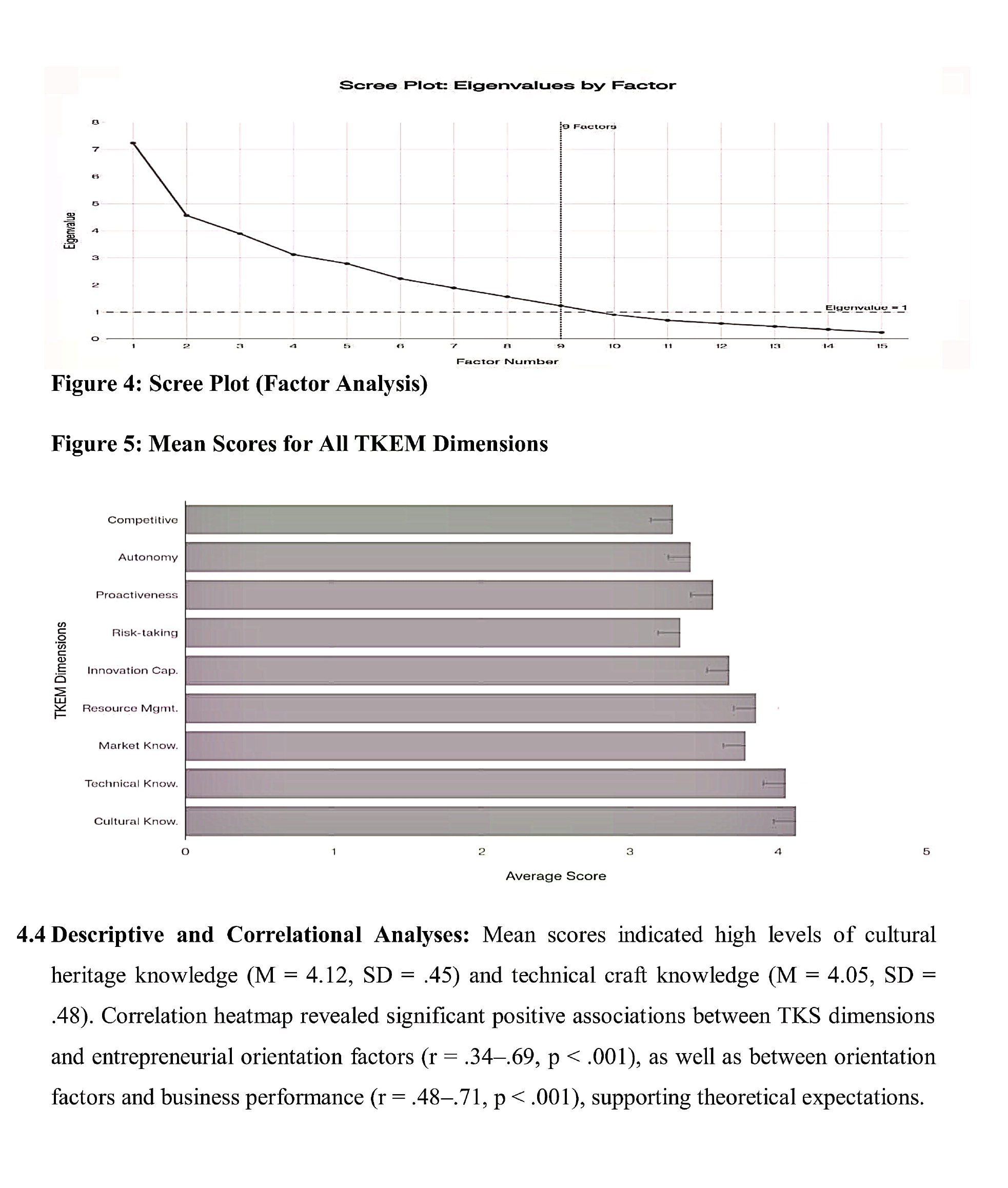

Following these qualitative inputs, an expert panel of 10 academicians and practitioners rated each item for content validity using the Content Validity Ratio (CVR) method. Items with CVR values below the threshold of 0.62 were discarded or revised, resulting in a refined set of 45 items. In the pilot phase (n = 50), Exploratory Factor Analysis (EFA) with principal axis factoring and Promax rotation assessed the emergent factor structure. Items exhibiting low communalities (<0.40), cross-loadings (> 0.30 on multiple factors), or factor loadings below 0.50 were removed, yielding a 32-item scale that mapped onto nine distinct dimensions.

1.4 Data Collection & Sample

Data collection employed a cross-sectional survey design administered between May and July 2025. A hybrid approach of purposive and snowball sampling targeted entrepreneurs deeply engaged in traditional crafts across the Kashmir Valley’s districts, ensuring representation of both urban and rural artisans. Inclusion criteria required participants to have operated their craft-based enterprise for at least one year.

The main study sample comprised 350 respondents, sufficient for Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA) given the recommended item-to-participant ratio of 1:10. A separate validation sample of 200 respondents was collected to evaluate the replicability of the factor structure and the generalizability of model fit indices.

Questionnaires were distributed in person and electronically via a secure online platform, accompanied by informed consent forms detailing study objectives, confidentiality assurances, and the voluntary nature of participation. Trained research assistants fluent in Kashmiri and Urdu facilitated data collection sessions, clarifying any respondent queries and ensuring accurate completion of all 5-point Likert items.

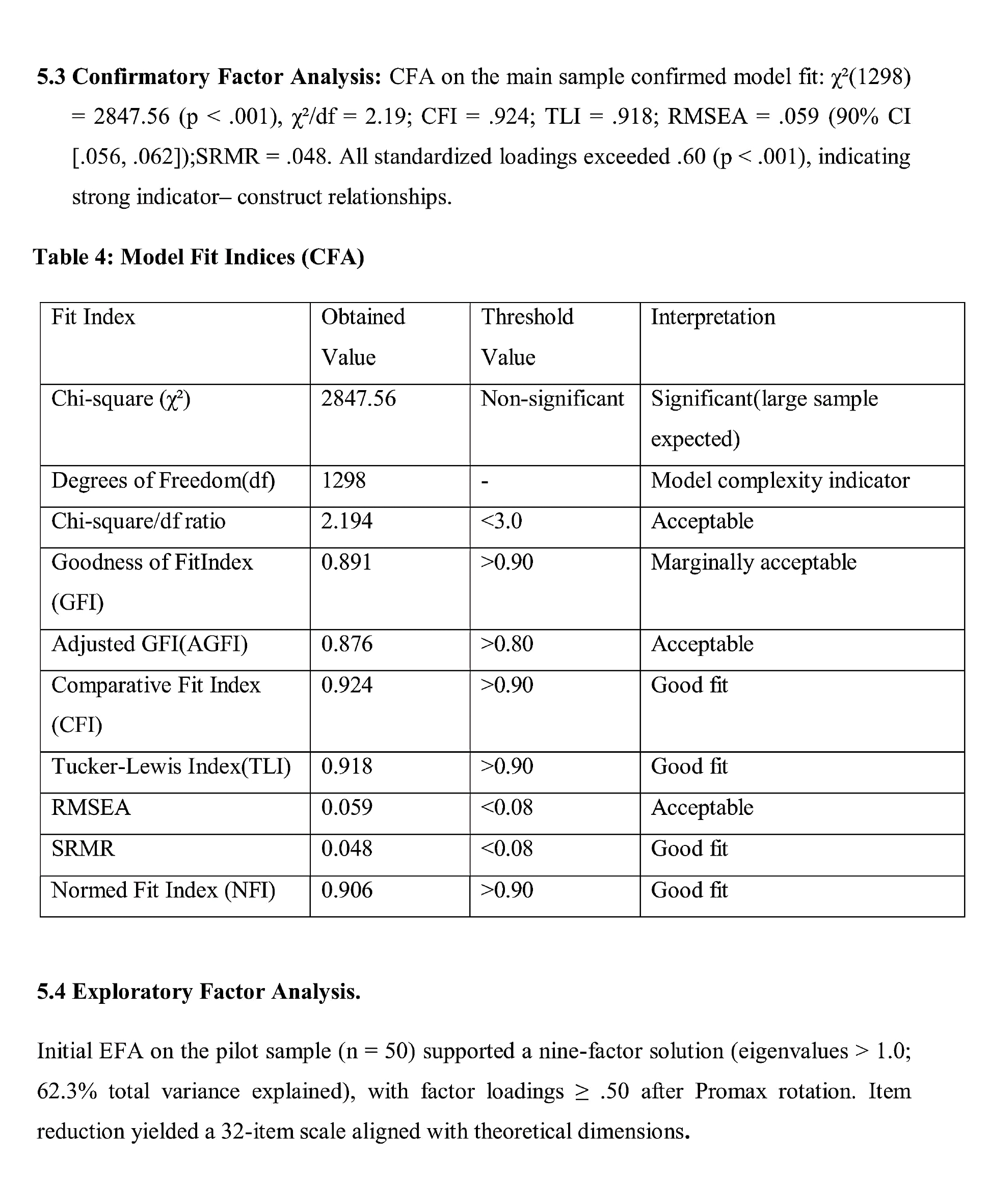

1.5 Reliability & Validity

Reliability of the TKEM scale was assessed through internal consistency metrics. Cronbach’s alpha coefficients for each dimension ranged from 0.785 to 0.892, exceeding the conventional threshold of 0.70, while Composite Reliability (CR) values ranged from 0.792 to 0.897, confirming stable inter-item correlations and homogeneity of constructs.

Construct validity was established via CFA using AMOS 26.0. The nine-factor model demonstrated adequate fit (χ²/df = 2.19; CFI = 0.924; TLI = 0.918; RMSEA = 0.059; SRMR = 0.048), supporting the hypothesized structure. Convergent validity was confirmed by average variance extracted (AVE) values exceeding 0.50 for seven of nine dimensions, with two dimensions marginally below but deemed acceptable given strong factor loadings (0.66–0.85). Discriminant validity was evaluated by comparing the square roots of each AVE with inter-construct correlations; in all cases, the AVE square roots were greater, indicating that each dimension measured a distinct aspect of traditional knowledge-based entrepreneurship. Finally, cross-validation in the separate sample (n = 200) confirmed the CFA results, with minimal changes in fit indices (< 0.02 difference), demonstrating the scale’s robustness across independent datasets. This thorough reliability and validity evidence highlights the TKEM scale’s appropriateness for scholarly research and practical assessment of traditional knowledge-based entrepreneurship in the Kashmir Valley.

Table 1: Methodology Summary

| Research Component | Description/Specification | Rationale/Target Value |

|---|---|---|

| Research Design | Cross-sectional, Quantitative Survey Design | Appropriate for scale development/validation |

| Population | Traditional craft entrepreneurs in the Kashmir Valley | Ensures cultural authenticity & Knowledge |

| Sampling Method | Purposive / Snowball / Stratified | Diversity & access to hard-to-reach groups |

| Sample Size | n = 350 (Main), 50 (Pilot), 200 (Validation) | Sufficient for robust analysis |

| Data Collection | Structured Questionnaire, 5-point Likert Scale | Standard measurement approach |

| Analysis Technique | EFA, CFA, SEM (SPSS & AMOS) | Comprehensive modern analysis |

| Reliability Measure | Cronbach’s Alpha, Composite Reliability | α > 0.70, CR > 0.70 |

| Validity Assessment | Content, Construct, Convergent, Discriminant Validity | Robust measurement standards |

2. Discussion & Results

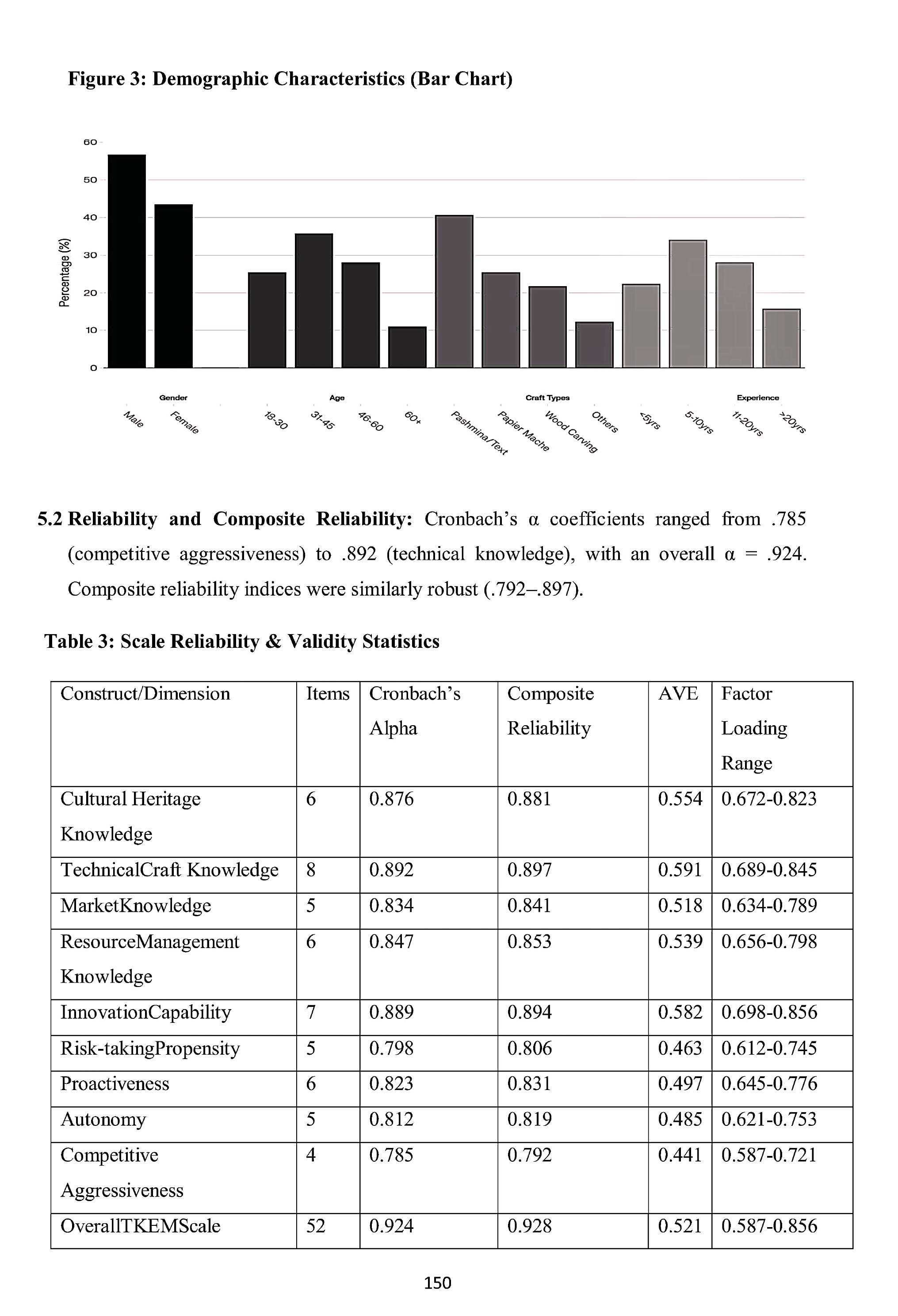

2.1 Sample Characteristics: Of the main sample (N = 350), 56.6% were male, 43.4% female; age distribution concentrated in 31–45 years (35.7%) and 46–60 years (28.0%); educational attainment spanned below graduation (19.1%) to post-graduation (28.0%); craft types included Pashmina/textiles (40.6%), papier-mâché (25.4%), and wood carving (21.7%) .

Table 2: Sample Characteristics

| Demographic Variable | Category | Frequency (n) | Percentage (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male | 198 | 56.6 |

| Female | 152 | 43.4 | |

| Age Groups | 18-30 | 89 | 25.4 |

| 31-45 | 125 | 35.7 | |

| 46-60 | 98 | 28.0 | |

| Above 60 | 38 | 10.9 | |

| Education Level | Below Graduation | 67 | 19.1 |

| Graduation | 156 | 44.6 | |

| Post-Graduation | 98 | 28.0 | |

| Others | 29 | 8.3 | |

| Traditional Craft Type | Pashmina/Textiles | 142 | 40.6 |

| Papier Mache | 89 | 25.4 | |

| Wood Carving | 76 | 21.7 | |

| Others | 43 | 12.3 | |

| Business Experience | <5 years | 78 | 22.3 |

| 5-10 years | 119 | 34.0 | |

| 11-20 years | 98 | 28.0 | |

| >20 years | 55 | 15.7 |

3. Discussion

Findings confirm the multidimensionality and psychometric rigor of the TKEM scale. The Indian Knowledge System provides essential context for sustainable and value-driven entrepreneurship, underscoring the significance of cultural preservation and rural economic resilience. Policies supporting market access, government incentives, and institutional capacity can amplify outcomes.

The findings of this study make several important contributions to the literature on entrepreneurship measurement & Indigenous Knowledge Systems (IKS). First, by developing and validating the Traditional Knowledge-Based Entrepreneurship Measurement (TKEM) scale, this research addresses a persistent methodological gap in entrepreneurship scholarship. Existing entrepreneurial orientation scales have been criticized for insufficiently capturing the unique, culturally embedded resources that drive value creation in traditional communities (Clark et al., 2025; Lumpkin & Dess, 1996). The TKEM scale overcomes this limitation by incorporating four key dimensions of traditional knowledge—cultural heritage, technical craft expertise, market knowledge, and resource management knowledge—together with five entrepreneurial orientation dimensions derived from established theory (Cheteni & Umejesi, 2024; Maheshwari, 2024).

Second, the rigorous multi-phase instrument development process enhances both content validity and cultural relevance. The initial item pool, informed by comprehensive literature review and expert interviews, reflected best practices in scale development (Hinkin, 1998; Lawshe, 1975). Subsequent focus groups with Kashmiri artisans ensured that items resonated with lived experiences of traditional entrepreneurs and were linguistically and culturally appropriate. The content validity ratio (CVR) exercise, followed by pilot EFA and confirmatory CFA in two independent samples, provided robust evidence of the scale’s factorial validity and reliability (Fornell & Larcker, 1981). Cronbach’s alpha coefficients (.785–.892) and composite reliability indices (.792–.897) consistently exceeded recommended thresholds, reinforcing the scale’s internal consistency (Nunnally & Bernstein, 1994).

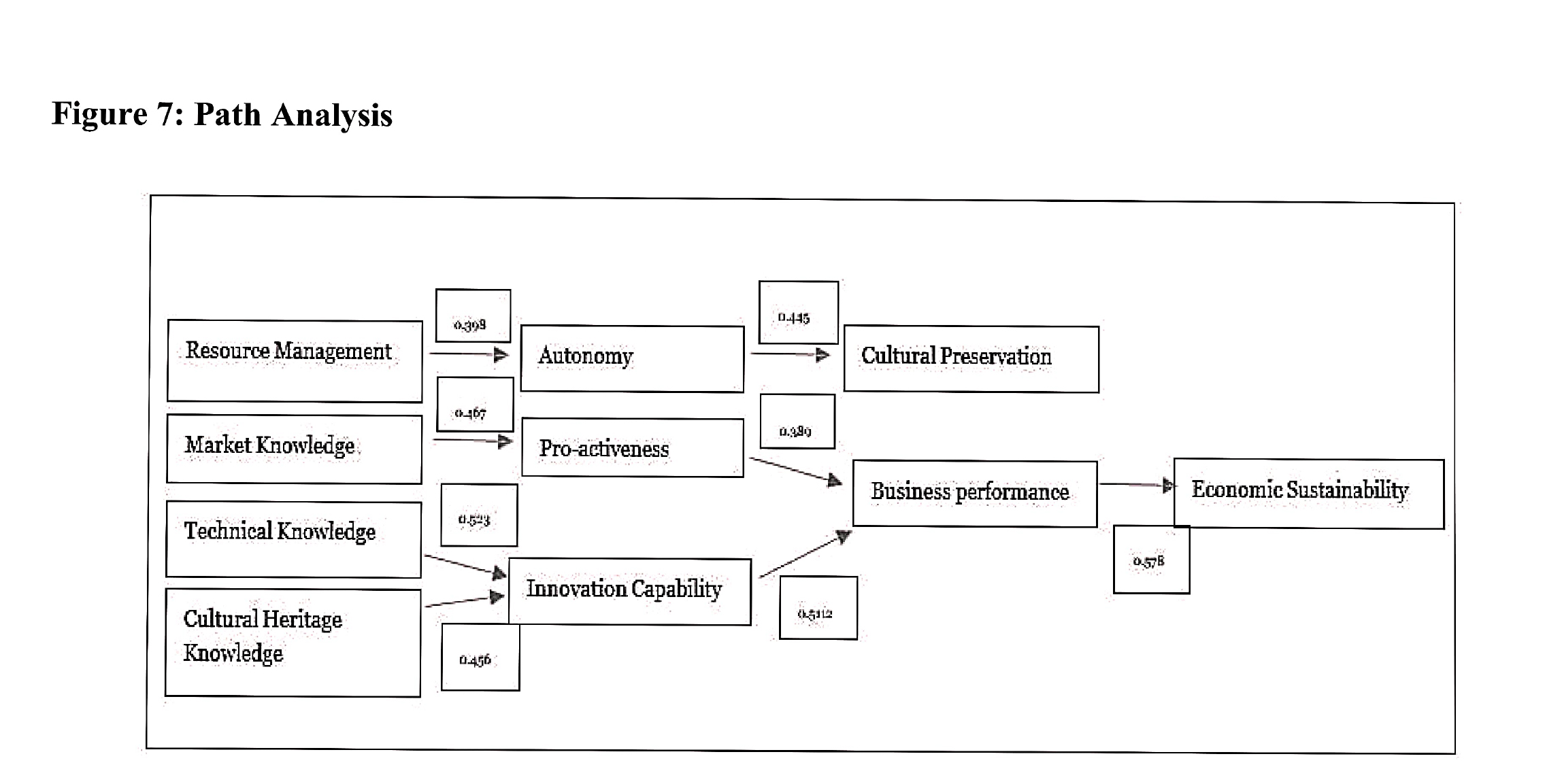

Third, the structural equation model (SEM) yielded theoretically coherent and empirically robust insights into how traditional knowledge dimensions influence entrepreneurial orientation and performance. Technical craft knowledge exerted the strongest direct effect on innovation capability (β = .523), underscoring the centrality of domain-specific expertise in sparking creative problem-solving within artisanal ventures. Cultural heritage knowledge also made a significant contribution to innovation (β = .456), demonstrating that generative engagement with tradition can catalyze novel product and process designs. The paths from innovation capability and proactiveness to business performance (β = .512 and .389, respectively) align with the broader entrepreneurial orientation literature, confirming that firms that combine tradition and innovation achieve superior outcomes (Rauch et al., 2009).

Furthermore, the novel path linking autonomy to cultural preservation (β = .445) represents an important theoretical extension. While autonomy has been conceptualized as an entrepreneurial orientation dimension reflecting self-directed decision-making, its role in sustaining intangible cultural heritage has received scant empirical attention. This result suggests that entrepreneurs who act independently and pursue self-determined strategies may be more effective custodians of traditional practices, likely because they can resist external pressures to standardize or commodify cultural products.

The model’s explanatory power was strong for business performance (R² = .567) and innovation capability (R² = .423), yet more modest for proactiveness (R² = .218), autonomy (R² = .158), and cultural preservation (R² = .198). These lower R² values indicate that additional predictors—such as social capital, institutional support, or individual values—may further explain variance in these constructs (Nahapiet & Ghoshal, 1998; Zahra & George, 2002). Future research might integrate these antecedents to build a more comprehensive model of traditional knowledge-driven entrepreneurship.

From a practical standpoint, the TKEM scale offers policymakers, development practitioners, and industry associations a reliable diagnostic tool for assessing the strengths and gaps in traditional knowledge entrepreneurship. Quantitative profiling of cultural heritage knowledge, technical expertise, and market orientation can inform targeted training programs, financial incentives, and market linkage initiatives. For example, districts scoring low on resource management knowledge might benefit from capacity-building workshops in sustainable raw material sourcing and inventory control. Institutions such as the Jammu & Kashmir Handicrafts Development Corporation could employ the scale to monitor the impact of heritage-preservation policies on entrepreneurial performance and community well-being.

Finally, this study contributes to broader debates on sustainable development and cultural resilience. By empirically demonstrating the linkages between traditional knowledge, entrepreneurial innovation, and economic sustainability (β = .578 for business performance → economic sustainability), the research supports the integration of cultural preservation into economic planning agendas (UNESCO, 2015). It underscores the potential of heritage-based enterprises to generate livelihoods while maintaining ecological and social harmony, aligning with United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (SDG 8: Decent Work and Economic Growth; SDG 11: Sustainable Cities and Communities).

4. Limitations

Despite its contributions, this study has several limitations that merit consideration. First, the cross-sectional nature of the research design limits the ability to draw definitive causal inferences regarding the relationships among traditional knowledge dimensions, entrepreneurial orientation factors, and performance outcomes. Longitudinal data collection would enable examination of temporal dynamics and stability of the TKEM scale’s factor structure and predictive validity over time. Second, the purposive and snowball sampling approach, while effective for targeting hard-to-reach traditional artisans, may introduce selection bias and limit the generalizability of findings beyond the Kashmir Valley context. Future research should employ probability-based sampling methods across multiple regions to enhance external validity. Third, although the TKEM scale encompasses key individual-level constructs, firm-level variables—such as organizational structure, access to finance, and marketing capabilities—were not included and may account for additional variance in business performance and cultural preservation. Incorporating these macro-level factors would provide a more comprehensive understanding of traditional knowledge-driven entrepreneurship. Finally, while the study secured content and construct validity through rigorous expert review and CFA, the marginal AVE values for two dimensions suggest that refinement of certain items may further strengthen convergent validity. Continued scale optimization and replication in diverse cultural settings are recommended to confirm the robustness of the nine-factor solution.

5. Conclusion

This research presents the first empirically validated measurement instrument for traditional knowledge-based entrepreneurship, integrating culturally embedded dimensions of the Indian Knowledge System with established entrepreneurial orientation constructs. The TKEM scale demonstrates robust psychometric properties, with strong internal consistency and factorial validity across independent samples. The structural equation model underscores the pivotal role of technical craft expertise and cultural heritage knowledge in fostering innovation capability, which, in turn, drives superior business performance and economic sustainability. The novel linkage between entrepreneurial autonomy and cultural preservation highlights the potential for self-directed strategies to safeguard intangible heritage while generating livelihoods. By offering a rigorous, context-specific tool, this study equips researchers, policymakers, and practitioners with actionable insights to assess and enhance traditional knowledge entrepreneurship. Future investigations employing longitudinal designs, expanded geographic samples, and multi-level analyses will further elucidate the mechanisms through which heritage-based entrepreneurship contributes to sustainable development and cultural resilience.

References

- Barney, J. (1991). Firm resources and sustained competitive advantage. Journal of Management, 17(1), 99–120. https://doi.org/10.1177/014920639101700108

- Cheteni, P., & Umejesi, I. (2024). Indigenous knowledge in entrepreneurship and cultural tourism in rural areas. Comparative Sociology, 23, 340–359.

- Clark, D. R., Covin, J. G., & Pidduck, R. J. (2025). Individual entrepreneurial orientation: Scale development and validation. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 49(3), 668–710. https://doi.org/10.1177/10422587241279900

- Fornell, C., & Larcker, D. F. (1981). Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. Journal of Marketing Research, 18(1), 39–50. https://doi.org/10.1177/002224378101800104

- Hinkin, T. R. (1998). A brief tutorial on the development of measures for use in survey questionnaires. Organizational Research Methods, 1(1), 104–121. https://doi.org/10.1177/109442819800100106

- Lawshe, C. H. (1975). A quantitative approach to content validity. Personnel Psychology, 28(4), 563–575. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1744-6570.1975.tb01393.x

- Majeed, M., & Muzaffar, A. (2025). Livelihood of Kashmiri Handicraft Artisans: challenges and Prospects. South Asia Research. https://doi.org/10.1177/02627280251347981

- Lumpkin, G. T., & Dess, G. G. (1996). Clarifying the entrepreneurial orientation construct and linking it to performance. Academy of Management Review, 21(1), 135–172. https://doi.org/10.5465/amr.1996.9602161568

- Maheshwari, K. A. (2024). Integrating Indian knowledge systems into ethical entrepreneurship: Analyzing emerging trends and their influence on modern business and commerce. Research Expression, 11(7), 33–42.

- Nahapiet, J., & Ghoshal, S. (1998). Social capital, intellectual capital, and the organizational advantage. Academy of Management Review, 23(2), 242–266. https://doi.org/10.5465/amr.1998.533225

- Nunnally, J. C., & Bernstein, I. H. (1994). Psychometric theory (3rd ed.). McGraw-Hill.

- Rauch, A., Wiklund, J., Lumpkin, G. T., & Frese, M. (2009). Entrepreneurial orientation and business performance: An assessment of past research and suggestions for the future. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 33(3), 761–787. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-6520.2009.00308.x

- Towseef Mohi Ud Din. (2015). A Study On The Different Delightful Craft Work In Kashmir. The International Journal of Social Sciences and Humanities Invention, 2(04), 1213–1215.

- UNESCO. (2015). The role of culture in sustainable development. United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization.

- WIPO. (2020). Documenting Traditional Knowledge: A Toolkit. World Intellectual Property Organization.

- Zahra, S. A., & George, G. (2002). Absorptive capacity: A review, reconceptualization, and extension. Academy of Management Review, 27(2), 185–203. https://doi.org/10.5465/amr.2002.6587995