Subscribe now to get notified about IU Jharkhand journal updates!

Transactional Leadership Behaviour And Workers Emotional Labour In Nigerian Hospitality Industry

Abstract :

This study investigates the effect of transactional leadership behaviour on workers emotional labour in Nigerian hospitality industry. Cross sectional research survey was employed in the study. Two hundred and sixty workers were surveyed from twenty selected four star hotels in Abakaliki with a sample size of one hundred and fifty five. Questionnaire was used as an instrument for data collection. Cronbach α was used to determine the instrument reliability. Linear regression was used to analysed the hypotheses. The study found that transactional leadership behaviour dimensions have positive significant effect on the measures of workers emotional labour in Nigerian hospitality industry. This study concludes that transactional leadership behaviour that is measured in term of transactional leadership behaviour dimensions such as contingent rewards and active management by exception increases workers emotional labour in Nigerian hospitality industry. The implication of this study is that hospitality practitioners and managers should employ transactional leadership behaviour to influence their workers by rewarding them for their performance and effectiveness.

Keywords :

Transactional leadership, workers emotional labour, deep acting, surface acting, contingent rewards, active management by exception.1. Introduction

Workers emotional labour (WEL) has been a major discourse amongst scholars in hospitality management, tourism, marketing, management quite apart from human resource management disciplines. This is because of how relevant the concept is to customer service delivery and customer satisfaction. Service oriented firms such as hospitality industry requires workers to display facial appealing emotions that will attract and retain customers. Right from the inception of employee admission to socialization, one of the baptism that employees receives is how to pretend to be happy at all times especially whenever customers are sighted from afar. Such pretentious and fake facial behaviour result to customer repeat purchase which leads to high profitability which is usually what most service organisations stand to achieve. Thus, workers emotional labour is exhibited in the form of deep acting and surface acting. Deep acting behaviour emanate from the innermost being of the employee whereas surface acting are fake smiles that workers are expected to display at the workplace especially when customers are sighted. Drawing from the above, workers emotional labour has been shown as predictor of organisational performance and effectiveness (Schaubroeck and Jones, 2000). Kumar, Shankar and Singh (2010) argued that workers emotional labour promotes organisational reputation. Rithi and Harold (2014) added that emotional management has become an instrument of success in service enterprises.

However, workers emotional labour (WEL) would not have been feasible without the influence of the organiaational leader (manager) who instructs, directs and control the affairs of the workplace. Leadership behaviour has been affirmed as the enhancer of emotional labour (Humphrey, Pollack and Hawver, 2008). One of the antecedents of leadership that managers employed to influence their subordinates is transactional leadership (TL) which focuses on exchange of work and reward. Odumeru and Ifeanyi (2013) argued that managers that influence their workers through give and take approach achieve their goals compared to their counterparts that focus more on the task alone. It has been shown that for employees to be motivated emotionally to the extent of going beyond their job description, managers need to understand the dimensionality of transactional leadership (Sundi, 2013; Ismail, Mohamad, Mohamed, Rafiuddin and Zhen, 2010). It is against this premise that Bass and Bass (2008) argued that top level managers can be more effective if they can influence their subordinates through transactional leadership exchange.

Nevertheless, trend of studies on workers emotional labour have been investigated in service oriented firms. Chao, Xinmei and Zizhen (2013) examined emotional labor strategies and service performance in China local restaurants. Their result shows that surface acting decreases employee creativity and extra role performance, while deep acting increases employee creativity. Yeliz, Zübeyir and Sabahat (2014) examined the relationship between emotional labor and job performance in private bank in Denizli. Their finding indicated that task performance has negative significant relationship with surface acting while innovative job performance has positive significant relationship with deep acting. Norzalita, Bita, Faridahwati and Ahmad (2016) examined customer perception of emotional labor of airline service employees and customer loyalty intention in Kuala Lumpur. Finding of their study revealed that perceived employee deep acting was positively and significantly associated with perceived customer orientation and perceived service quality. Most of the above trend of studies was not carried out in Nigeria work setting and also, they did not investigate the effect of transactional leadership behaviour on workers emotional labour in the hospitality industry. This is what has propelled the researchers to investigate the effect of transactional leadership behaviour (TLB) on workers emotional labour (WEL) in Nigerian hospitality industry.

Review Of Literature

Transactional Leadership

Transactional leadership (TL) was propounded by Burns (1978). Bass (1985) argued that transactional leaders focus on the economic exchange to meet subordinates’ current material and physiological needs in return for the services rendered in the workplace. It has been shown that leaders or managers that exercise transactional approach to leadership promises to reward their subordinates by influencing them to perform tasks in order to achieve organisational goals (Bass, 1990). Robbins and Judge (2018) perceived TL as a type of leadership where managers who guide or stimulate their subordinates in the direction of established objectives by clarifying what should be done and how it should be done. For Mullins (2011), TL is based on mutual relationship of exchange process of ‘I will give you this, if you do this’. On the other hand, Jones and George (2016) asserted that transactional leadership motivates subordinates by rewarding them for high performance and punishing them for low performance. Burns (1978) described transactional leadership as more of “give and take” relationship in the workplace, where exchange is a major form of interaction between the superior and subordinate. For Luthans (2011), transactional leadership involves an exchange relationship between leaders and followers. Transactional leadership is a style of leadership in which the leader promotes compliance of his followers through rewards and punishments (Odumeru and Ifeanyi, 2013; Obiwuru, Okwu, Akpa and Nwankwere, 2011; Nongo, 2015). Transactional leadership has assisted many firms to improve their performance. In support of this argument, McShane and Von Glinow (2018) accentuated that transactional leadership assist firms to achieve their current objectives more efficiently such as linking their performances to ewards and ensuring that employees have the resources needed to get the job done.

Nevertheless, previous studies on transactional leadership indicated positive significant effect on other criterion variables. Zohra, Mukaram and Syed (2018) examined the impact of transactional leadership and transformational leadership on employee performance in Pakistan. Their finding revealed that transactional leadership has significant impact on employee performance compared to transformational leadership. Sundi (2013) examined the effect of transformational leadership and transactional leadership on employee performance in Southeast Sulawesi. Sundi’s finding show that transactional leadership has positive and significant effect on employee performance. Feng, Xin and Yang (2010) investigated the effects of transactional leadership, psychological empowerment and empowerment climate on creative performance of subordinates in China. Finding of their study shows that transactional leadership behaviour is positively associated with subordinates’ creative performance in teams with higher empowerment climate. Syed, Jaffar, Shen, Muhammad and Tayyaba (2017) examined the role of transactional leadership in creating the organizational creativity through knowledge sharing behavior between employees and leaders. Findings of their study indicated that transactional leadership and knowledge sharing have positive relationship with creativity. Ayla (2013) examined the possible effects of transactional and transformational leadership styles on entrepreneurial orientation in Istanbul. Ayla’s finding showed that transactional leadership has significant positive effect on proactiveness.

Dimensions Of Transactional Leadership

Dimensions of transactional leadership include; contingent rewards, active management by exception, and passive management by exception as well as laissez-faire (Bass, 1990; Schermerhorn, Hunt and Osborn, 2000 cited in Adnan and Mubarak, 2010). Contingent rewards implies that manager exchange rewards for the effort that employee put in to perform a task and promises to reward such employee for good performance and recognizes accomplishments (Luthans,2011). Active management by exception is a transaction leadership behaviour where leader or manager monitor subordinates performance, watches the errors from the rules and regulations, anticipate problems and issues, take drastic actions according to their performance and control such deviation to resolve the problems (Odumeru and Ifeanyi, 2013). In passive management by exception, managers or supervisors that employ passive management by exception tend not to bother fixing organisational problems except when the challenge seems to be very serious.

Workers Emotional Labour (Wel)

Workers emotional labour is a behaviour where workers are expected to smile at customers at all times even when he/she is not in the mood to do so. In service organisations, workers are informed by their superior to welcome customers with a smiling face. It is based on this premise that an employee becomes a smiling actor whenever a customer walks in. Emotional labour was coined by Hochschild (1983) in her work titled “The Managed Heart: Commercialization of Human Feeling”. Her inspiration on emotional labour was based on the behaviour of Delta Airlines flight attendants towards their passengers. Hochschild’s argument is based on the implicit coerciveness by management to manipulate workers emotions for profit purpose and use their emotions as a commodity (Rajesh and Dheeraj, 2015). Emotional labour is the effort, planning and control needed to express organizationally desired emotions during interpersonal transactions (McShane and Von Glinow, 2018; Robbins, Judge and Sanghi, 2009). Hazel-Ann (2007) perceived emotional labour as service with a smile. Austin, Dore, and O’Donovan (2008) define emotional labour as the process where employee displays appropriate emotional behaviour that might or might not correspond to the employee true emotions. Norzalita, Bita, Faridahwati and Ahmad (2016) stressed that emotional labour is a kind of impression management that helps an employee to direct his/her behaviour. Brown (2010) described emotional labour as part of the work role that includes display or restriction of emotions to comply with the organizational, social or occupational rules and norms, and is a vital facet of working life of the employees. Groth, Hennig-Thurau and Walsh (2009) contended that emotional labour focuses on the self regulatory processes that employees use to display emotions in compliance with organizational expectations. Emotional labour implies when employees suppressed, hide, fake or strengthen their emotions or their expression (Justyna and Kinga, 2016).

Measures Of Workers Emotional Labour

Morris and Feldman (1996) argued that workers emotional labour has four dimensions; attention of emotional labor, frequency of emotional labor, emotional dissonance and kind of emotional labour. It has also been shown that deep acting (displaying genuine emotion) and surface acting (displaying fake emotions) are the most widely researched indicators of emotional labour (Hochschild, 1983; Kruml and Geddes, 2000; Zapf, 2002). Deep acting is refers to as acting in good faith as it involves employee trying to change his/her internal emotional states of to match organizational expectations (Grandey, 2003; Rafaeli and Sutton, 1987). Deep acting also implies how an employee modifies his/her emotion to match the organizationally required emotion (Rithi and Harold, 2014). Groth, Hennig-Thurau and Walsh (2009) argued that deep acting are more likely to be more genuine than surface acting which only occurs when employees change their outward appearance without genuinely altering how they actually feel. On the other hand, surface acting involves acting or expressing an emotion on the surface without actually feeling them (Rithi and Harold, 2014). In surface acting, workers that are frustrated may suppress their anger and simply smile at an annoying customer, thus “putting on a mask” without actually changing their feelings and expressing feigned rather than genuine emotions (Grandey, 2003). Robbins, Judge and Sanghi (2009) added that when a worker smiles at a customer even when he/she doesn’t feel like it, he/she are surface acting. On another hand, when a worker is trying to genuinely feel more empathy for his/her customer or client, such employee is deep acting (Robbins, Judge and Sanghi, 2009). It has been shown that surface acting deals with one’s displayed emotions, while deep acting deals with one’s felt emotions (Robbins, Judge and Sanghi, 2009). Surface acting involves when an employee changes his/her emotional expression when dealing with clients, customers but only by putting on good appearance and presenting signs of required emotions, e.g. benevolence, enthusiasm or interest (Justyna and Kinga, 2016). Surface acting is divided into two components; hiding and faking emotions (Lee and Brotheridge, 2011). Faking emotions implies pretence feelings that is expected from an employee to expressed while hiding feelings is concerned with when an employee suppresses negative or adverse emotions or restraining expression of his/her true feelings or concealing them (Justyna and Kinga, 2016).

Theoretical Framework

The underlining theories of this study are affective event theory; theory X, leadership initiating structure theory and social exchange theory. Affective events theory demonstrates that employees react emotionally to things that happens to them at work and that this reaction influences their job performance and satisfaction (Robbins, Judge and Sanghi, 2009). The work environment includes everything surrounding the job - the variety of tasks and degree of autonomy, job demands, and these work events trigger both positive and negative emotional reactions that require expressing emotional labour (Robbins, Judge and Sanghi, 2009). On another hand, Theory X leadership assumption by Douglas McGregor is in line with transactional leadership behaviour as its negative assumptions on how workers dislike work; they should be coerced or strongly supervised as well as directed on what to do. However, another theory that correspond with transactional leadership behaviour is initiating structure which is a behavioral leadership theory advocated by Ohio State University. Initiating structure is a leader behaviour that organizes and defines what group members should be doing to maximize output (Kinicki and Kreitner, 2003). Social exchange theory assumes that two parties are in agreement to provide employment while the other provides the service to customers. In this exchange, workers expected to display emotions that will attract and retain the customers (emotional labour) while management provides the rewards (transactional leadership behaviour).

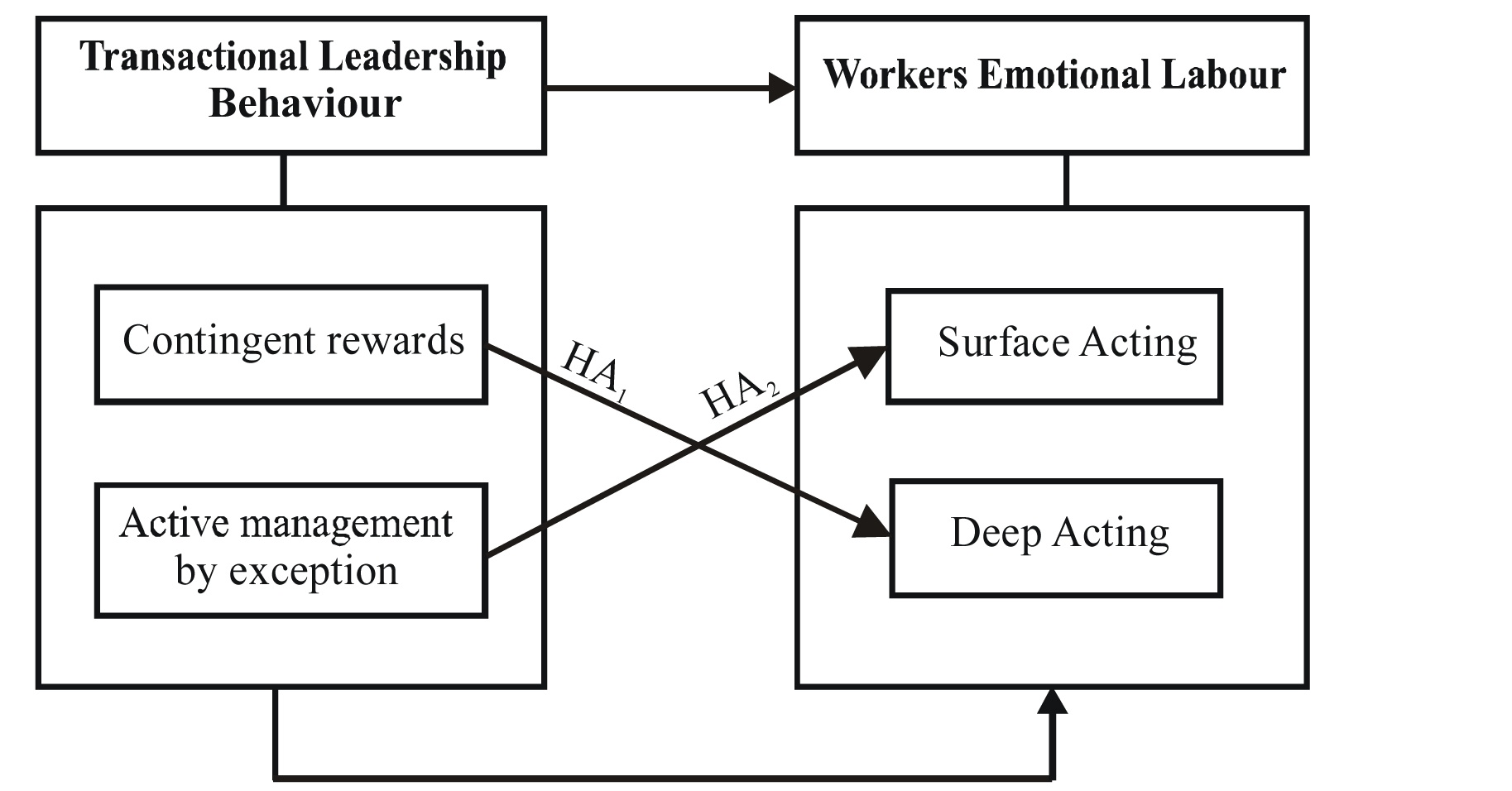

Figure 1.1: Conceptual framework showing the effect of transaction al leadership behaviour on workers emotional labour.

Research Hypotheses

In line with the above conceptual framework, the following research hypotheses were formulated.

HA1: Contingent rewards has significant effect on workers deep acting in Nigerian hospitality industry

HA2: Active management by exception has significant effect on workers surface acting in Nigerian hospitality industry

Research Methodology

Research design employed in this study is cross-sectional research survey. Sekaran and Bougie (2016) argue that a cross-sectional survey is a study undertaken by a researcher in which data are gathered just once, perhaps over a period of days or weeks or months, in order to answer a research question.

Population and Sampling

Target population of this study consists of four star hotels operating in Abakaliki, Nigeria while the sample frame is made up of twenty four star hotels operating in Abakaliki, Nigeria. A total of two hundred and sixty (260) workers comprising of hotel managers, front desk officers, supervisors and housekeepers were surveyed from the twenty selected four hotels in Abakaliki. Sample size of one hundred and fifty five (155) was ascertained using Krejcie and Morgan (1970).

Data Collection

Questionnaire was used to collect responses from one hundred and fifty five (155) participants. Out of one hundred and fifty five (155) copies of questionnaire administered, one hundred and thirty eight (138) copies were found useful and used for data analysis.

MEASURES

Face validity was used to ascertain the validity of the instrument while Cronbach Alpha test was employed to determine the reliability of the instrument. Dimensions of transactional leadership behaviour and measures of workers emotional labour falls within 0.07 and 0.8. This is in line with Nunnally and Bernstein (1994) benchmark for instrument reliability. Dimensions of transactional leadership behaviour were measured with 6-items developed by Bass and Avolio (1990). Workers emotional labour was measured with 6-items based on Grandey (2003), Brotheridge and Lee (2003) emotional labour questionnaire adapted by Groth, Hennig-Thurau and Walsh (2009). All of the questions were measured on a 5-point Likert-type scale ranging from 5=Very great extent, 4=Great extent, 3=Moderate extent, 2=Low extent, 1=Very low extent.

Method of Data Analysis

Descriptive statistics (frequency) was used to analyse respondents’ demographic characteristics such as gender of respondents, age brackets and educational qualifications while linear regression was used to analyse the hypotheses. Microsoft Excel (2007) was used for the analysis of the bar charts. The analysis was carried out with the aid of IBM Statistical package for social sciences (20.0).

Analysis and Results

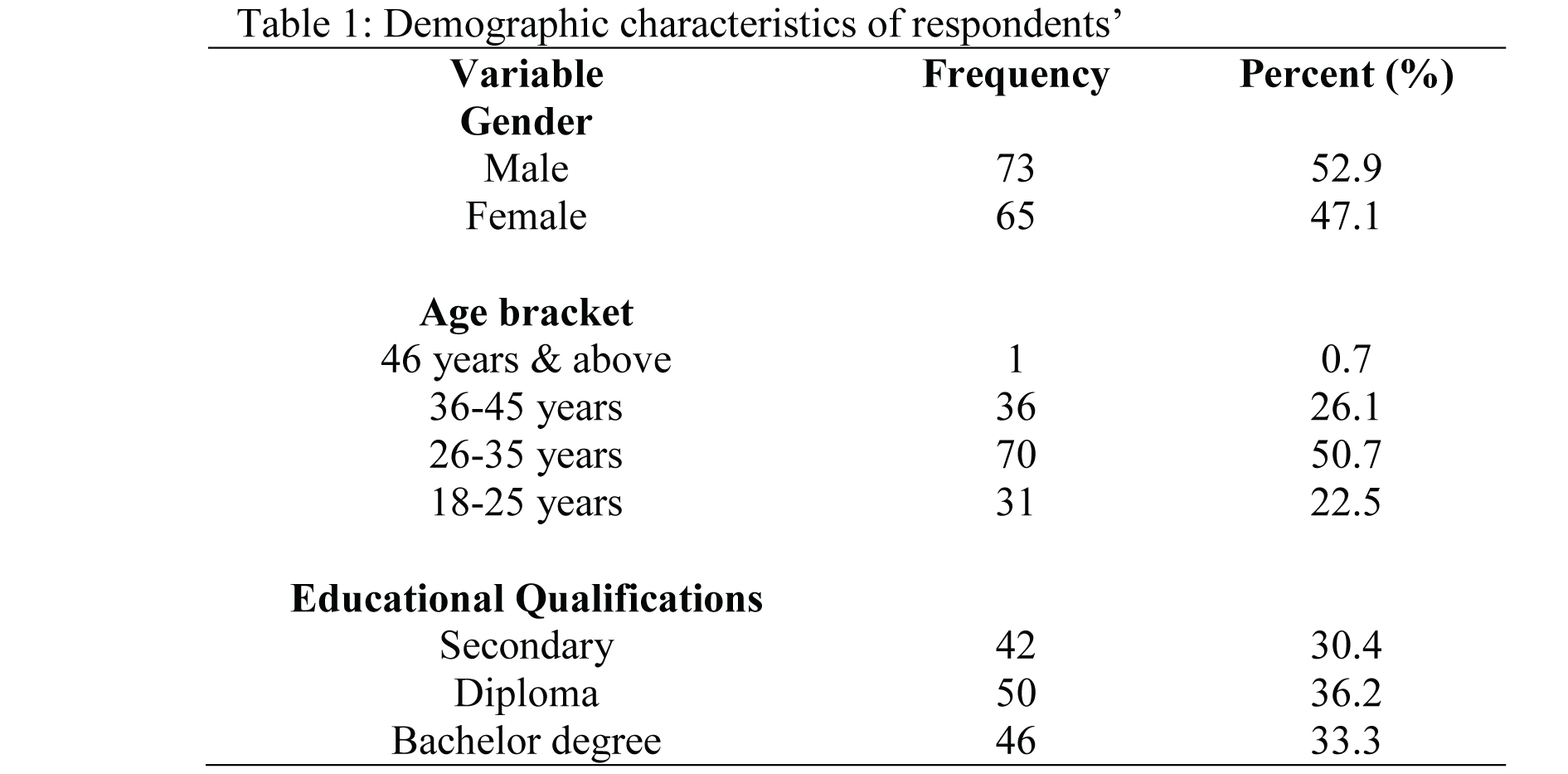

Table 1 above shows the analysis of demographic profiles of participants. 73 participants representing 52.9% are males; 65 respondents representing 47.1% are females. 1 respondent representing 0.7% falls within 46 years and above; 36 participants representing 26.1% are between 36-45 years; 70 respondents representing 50.7% are within 26-35 years; 31 participants representing 22.5% falls within 18-25 years. Educational qualifications of participants’ shows that 42 respondents representing 30.4% have attained secondary education; 50 respondents representing 36.2% hold diploma certificates; while 46 participants representing 33.3% hold bachelor degrees.

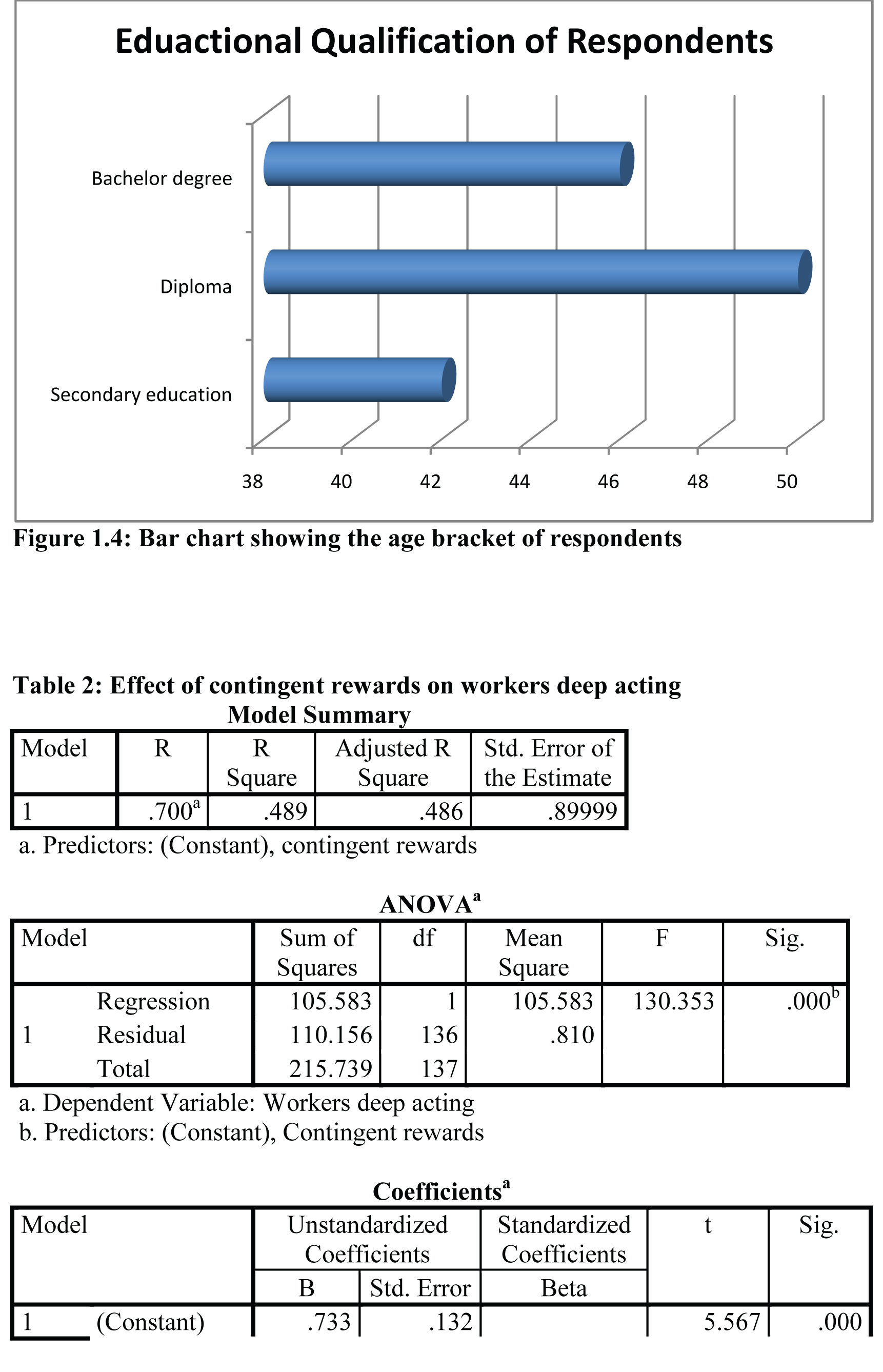

Table 2 above shows the result of linear regression analysis of contingent rewards on workers deep acting. The R shows a substantial correlation between the predictor variable and the dependent variable (workers deep acting) (R = .700a). The R-square value indicates that about 49% of the variance in workers deep acting is explained by the predictor variable. The β values indicate the relative influence of the entered variables, that is, contingent rewards has the greatest influence on workers deep acting (β = .700). The direction of influence for the predictor variable is positive. Secondly, F-ratio show that the predictor variable (contingent rewards) is statistically significant and predicted the criterion variable (workers deep acting), F(1,136) = 3.91, p<0.05, R2 =.489 and with a high degree of correlation (R=.700a). F calculated is greater than the tabulated (130.353 > 3.91). Since F calculated (130.353) is greater than the tabulated value (3.91), the null hypothesis is hereby rejected and alternate hypotheses accepted. The study therefore states that contingent rewards have positive significant effect on workers deep acting.

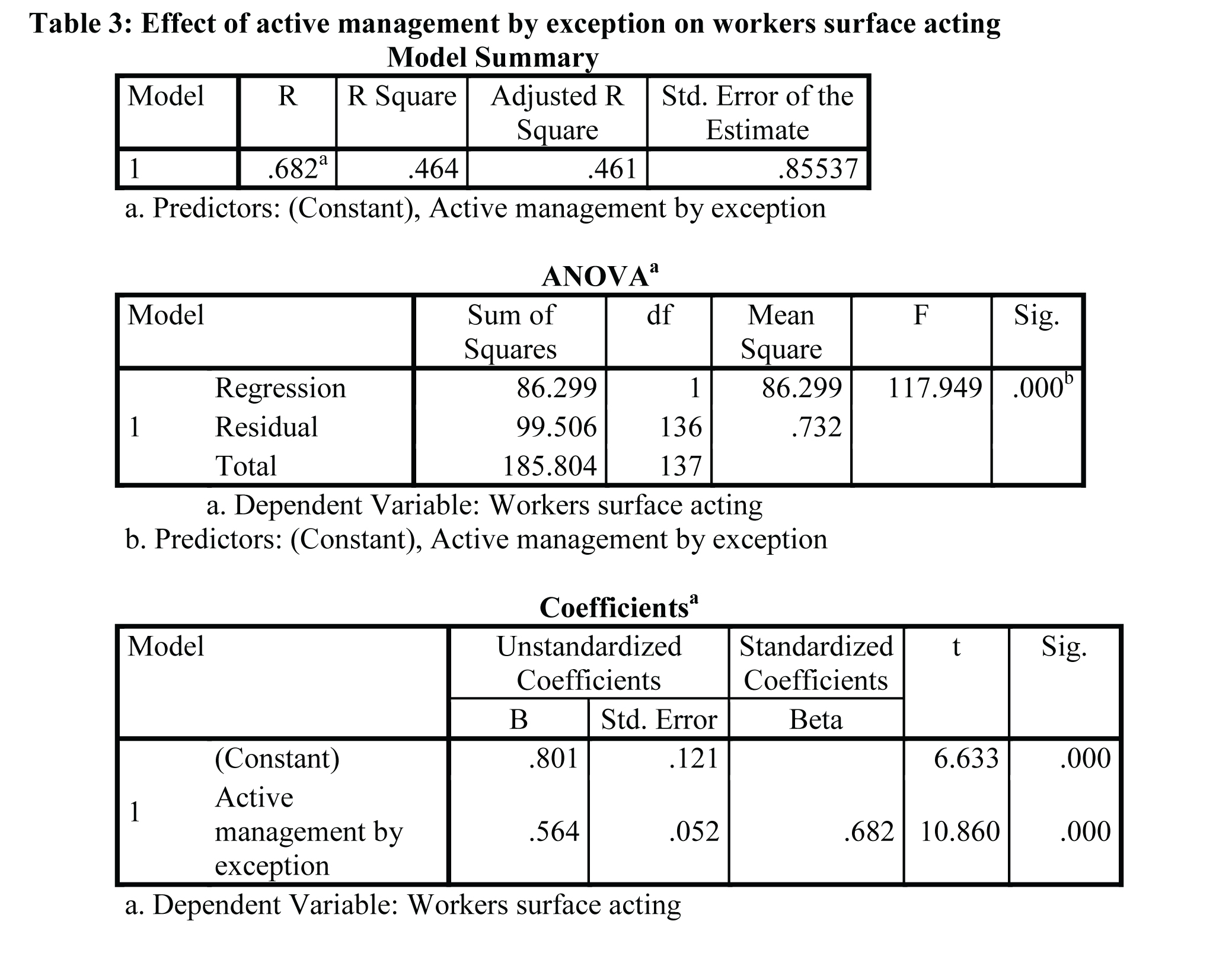

Table 3 above shows the result of linear regression analysis of active management by exception on workers surface acting. The R shows a substantial correlation between the predictor variable and the dependent variable (workers surface acting) (R = .682a). The R-square value indicates that about 46% of the variance in workers surface acting is explained by the predictor variable. The β values indicate the relative influence of the entered variable, that is, active management by exception has the greatest influence on workers surface acting (β = .682). The direction of influence for the predictor variable is positive. Secondly, F-ratio show that the predictor variable (active management by exception) is statistically significant and predicted the criterion variable (workers deep acting), F(1,136) = 3.91, p<0.05, R2 =.464 and with a high degree of correlation (R=.700a). F calculated is greater than the tabulated (117.949 > 3.91). Since F calculated (117.949) is greater than the tabulated value (3.91), the null hypothesis is hereby rejected and alternate hypotheses accepted. The study states that active management by exception has positive significant effect on workers surface acting.

Discussions

In line with the results above, this study found that transactional leadership behaviour dimensions have positive significant effect on the measures of workers emotional labour in Nigerian hospitality industry. These findings are line with previous empirical evidence. Zohra, Mukaram and Syed (2018) finding show that transactional leadership has significant impact on employee performance compared to transformational leadership. Sundi (2013) finding indicated that transactional leadership has positive and significant effect on employee performance. Feng, Xin and Yang (2010) finding shows that transactional leadership behaviour is positively associated with subordinates’ creative performance in teams with higher empowerment climate. Syed, Jaffar, Shen, Muhammad and Tayyaba (2017) findings indicated that transactional leadership and knowledge sharing have positive relationship with creativity. Ayla (2013) finding revealed that transactional leadership has significant positive effect on proactiveness.

Conclusion and Implication

This study concludes that transactional leadership behaviour that is measured in term of transactional leadership behaviour dimensions such as contingent rewards and active management by exception increases workers emotional labour in Nigerian hospitality industry. The implication of this study is that hospitality practitioners and managers should employ transactional leadership behaviour to influence their workers by rewarding them for their performance and effectiveness. This will promote the sustainability of hospitality industry in Nigeria and across the globe.

References

- Adnan, R., & Mubarak, H.H. (2010). Role of transformational and transactional leadership on job satisfaction and career satisfaction. BEH Business and Economic Horizons, 1(1), 29-38.

- Ayla, Z.Ö. (2013). Investigation of the effects of transactional and transformational leadership on entrepreneurial orientation. International Journal of Business and Social Research, 3(4),153-166.

- Bass, B.M. (1985). Leadership and performance beyond expectations. New York: Free Press.

- Bass, B.M. (1990). Bass and Stogdill’s handbook of leadership: Theory, research and Management Applications (3rd ed.). New York: Free Press.

- Bass, B.M., & Bass, R. (2008). The Bass handbook of leadership theory, research & managerial applications (4th ed.). London: Free Press.

- Brotheridge, C.M., & Lee, R.T. (2003). Development and validation of the emotional labour scale. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, 76, 365-379.

- Burns, J.M. (1978). Leadership. New York: Harper & Row.

- Chao, L., Xinmei, L., & Zizhen, G. (2013). Emotional labor strategies and service performance: The mediating role of employee creativity. The Journal of Applied Business Research, 29(5),1583-1596.

- Feng, W., Xin, Y., & Yang, D. (2010). Effects of transactional leadership, psychological empowerment and empowerment climate on creative performance of subordinates: A cross-level study. Front. Bus. Res. China, 4(1), 29–46.

- Grandey, A.A., (2003). When the show must go on: Surface acting and deep acting as determinants of emotional exhaustion and peer-rated service delivery. Academy of Management Journal, 46, 86–96.

- Groth, M., Hennig-Thurau, T., & Walsh, G. (2009). Customer reactions to emotional labor: The roles of employee acting strategies and customer detection accuracy. Academy of Management Journal, 52(5), 958–974.

- Hazel-Ann, M.J. (2007). Service with a smile: Antecedents and consequences of emotional labor strategies. Graduate Theses and Dissertations. http://scholarcommons.usf.edu/etd/2231.

- Hochschild, A.R. (1983). The managed heart: The commercialization of feeling. Berkeley: University of California Press.

- Humphrey, R.H., Pollack, J.M., & Hawver T. (2008). Leading with emotional labour. Journal of Managerial Psychology, 23(2), 151-168.

- Ismail, A., Mohamad, M.H., Mohamed, H.A,. Rafiuddin, N.M., & Zhen, K.W.P. (2010). Transformational and transactional leadership styles as a predictor of individual outcomes. Theoretical and Applied Economics, 17(6), 89-104.

- Jones, G.R., & George, J.M. (2017). Essentials of contemporary management (7th ed.). New York: McGraw-Hill Education.

- Justyna, M. & Kinga, K. (2016). Relationships between personality, emotional labor, work engagement and job satisfaction in service professions. International Journal of Occupational Medicine and Environmental Health,29(5), 767–782.

- Kinicki, A., & Kreitner, R. (2003). Organizational behavior: Key concepts, skills & practices. New York: McGraw-Hill Irwin.

- Krejcie, R.V., & Morgan, D.W. (1970). Determining sample size for research activities Educational and Psychological Measurement, 30, 607-610.

- Kruml, S.M., & Geddes, D. (2000). Exploring the dimensions of emotional labor: The heart of Hochschild’s work. Management Communication Quarterly, 14, 8–49.

- Kumar, S., Shankar, B., & Singh, A.P., (2010). Emotional labour and health outcomes: An overview of literature and preliminary empirical evidences. Indian Journal of Social Science Researches, 7(1), 83-89.

- Lee, R.T., & Brotheridge, C.M. (2011). Words from the heart speak to the heart. A study of deep acting, faking, and hiding among child care workers. Career Dev Int.,16,401–20.

- Luthans, F. (2011). Organizational behavior. An evidenced-based approach (12th ed.). New York: McGraw Hill Irwin.

- McShane, S.L., & Von Glinow, M.A. (2018). Organizational behavior. Emerging knowledge. Global reality (8th ed.). New York: McGraw-Hill Education.

- Morris, J.A., & Feldman, D.C. (1996). The dimensions, antecedents, and consequences of emotional labor. Academy of Management Review, 21(4), 986-1010.

- Mullins, L.J. (2011). Management & Organisational behaviour (9th ed.). England: Pearson Education Limited.

- Nongo, S. (2015). Effects of leadership style on organizational performance in small and medium scale enterprises (SMES) in Nigeria. International Journal of Research in Management & Business Studies, 2(2), 23-30.

- Norzalita, A.A., Bita, N., Faridahwati, M.S., & Ahmad, S.I.A. (2016). Customer perception of emotional labor of airline service employees and customer loyalty intention. ISSC 2016: International Soft Science Conference. The European Proceedings of Social and Behavioural Sciences.

- Nunnally, J.C., & Bernstein, I.H. (1994). Psychometric theory (3rd ed.). New York: McGraw-Hill, Inc.

- Obiwuru, T.C., Okwu, A.T., Akpa, V.O., & Nwankwere, I.A. (2011). Effects of leadership style on organizational performance: A survey of selected small scale enterprises in Ikosi-Ketu council development area of Lagos state, Nigeria. Australian Journal of Business and Management Research, 1(7), 100-111.

- Odumeru, J.A., & Ifeanyi, G.O. (2013). Transformational vs. Transactional Leadership Theories: Evidence in Literature. International Review of Management and Business Research, 2(2),355-361.

- Rafaeli, A., & Sutton, R.I. (1987). Expression of emotion as part of the work role. Academy of Management Review, 12, 23–37.

- Rajesh, C., & Dheeraj, S. (2015). Managing emotions: Emotional labor or emotional enrichment. Indian Institute of Management Ahmedabad-380 015 India.2-24.

- Rithi, B., & Harold, A.P. (2014). Influence of emotional labour on general health of cabin crew and airline ground employees. Journal of Education & Social Policy, 1(2),40-50.

- Robbins, S.P. & Judge, T.A. (2018). Essentials of organizational behavior. Global Edition. England: Pearson Education Limited.

- Robins, S.P., Judge, T.A., & Sanghi, S. (2009). Organizational behavior (13th ed.). New Delhi: Prentice Hall.

- Schaubroeck, J., & Jones, J.R. (2000). Antecedents of workplace emotional labor dimensions and moderators of their effects on physical symptoms. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 21, 163-183.

- Schermerhorn, J., Hunt, J., & Osborn, R. (2000). Organizational Behaviour (7th ed.), New York: John Wiley & Sons, Inc.

- Sekaran, U., & Bougie, R. (2016). Research methods for business: A skill-building approach (7th ed.). United Kingdom: John Wiley & Sons Ltd.

- Sundi, K. (2013). Effect of transformational leadership and transactional leadership on employee performance of Konawe Education Department at Southeast Sulawesi Province. International Journal of Business and Management Invention, 2(12), 50-58.

- Syed, T.H., Jaffar, A., Shen, L., Muhammad, J.H., & Tayyaba, A. (2017). Transactional leadership and organizational creativity: Examining the mediating role of knowledge sharing behaviour. Congent Business & Management, 4(1361663), 1-11.

- Yeliz, M.B., Zübeyir, B., & Sabahat, B.K. (2014). The relationship between emotional labor and task/contextual/innovative job performance: A study with private banking employees in Denizli. European Journal of Research on Education, 2(2), 221-228.

- Zohra, K., Mukaram, A.K., & Syed, S.Z. (2018). Impact of transactional leadership and transformational leadership on employee performance: A case of FMCG industry of Pakistan. Industrial Engineering Letters, 8(3), 23-30.